Before they were robots, they were “androids” or “automatons.” The word “robot” is commonly accepted as having arrived in English through — of all places — a Czech play. “R.U.R.” made its public debut in Prague 102 years ago, yesterday. It would arrive in the States a year and a half later, with Spencer Tracy making his nonspeaking Broadway debut as one of Rossum’s titular Universal Robots.

The playwright Karel Čapek humbly noted the following decade that he couldn’t take full credit for the word’s origin. That honor belonged to his brother Josef, an accomplished painter and noted writer and poet in his own right:

“Listen, Josef,” the author began, “I think I have an idea for a play.”

“What kind,” the painter mumbled (he really did mumble, because at the moment he was holding a brush in his mouth). The author told him as briefly as he could.

“Then write it,” the painter remarked, without taking the brush from his mouth or halting work on the canvas. The indifference was quite insulting.

“But,” the author said, “I don’t know what to call these artificial workers. I could call them Labori, but that strikes me as a bit bookish.”

“Then call them Robots,” the painter muttered, brush in mouth, and went on painting. And that’s how it was. Thus was the word Robot born; let this acknowledge its true creator.

Maybe it’s better we wound up with a derivative of “robota,” rather than “labori,” as the latter too clearly betrays its underlying definition to English speakers. The former operates in the same ballpark, certainly, meaning “servitude or forced labor,” but that requires some knowledge of Czech not possessed by most native English speakers.

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin

Obviously, the definition is a problematic one. It humanizes these systems in way I suspect would make most uncomfortable. Though, for the record, Rossum’s robots didn’t need humanizing. They’re far removed from the commonly agreed-upon modern definition. They’re closer to organic beings, mixed with a little bit of poetic magic — more Pinocchio than Howdy Doody.

Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that questions of robotic agency date back even before the arrival of the word in English. At the risk of spoiling a 102-year-old play, so, too, does the concept of robot uprising. You can get as annoyed as you want at people who immediately jump to the idea of “robopocalypse” every time an advanced new system enters their Twitter feed, but the concept has been around a hell of a lot longer than any of us.

The flip side of this conversation is, of course, dehumanizing humans. It’s something I sometimes worry we risk with technology. It’s a conversation I’ve had with folks in many blue-collar positions. I still believe that technology can — and often does — make jobs better, whether it’s a robotic exoskeleton lightening the load or an autonomous cart moving goods around a warehouse. Technology can also open new avenues for pushing workers to their limit. Monitoring a worker’s whereabouts and output on a minute scale, for instance, does not allow time for humans to be human.

More relevant to the current economic situation, however, is something I’m trying to get better at myself. In some respects, evolution has fine-tuned our brains to understand abstraction. Take metaphor and symbolism in the art we make, for example. We’re good at creating these sorts of shortcuts to help understand the big ideas we’re not necessarily capable of putting into words.

We do, however, have our limits. Big numbers, for instance, can be extremely difficult to conceptualize on an individual scale. I understand that there’s a literal big difference between having $100 million and having $1 billion. But if I want to actually get anything done today, I’ll simply accept them both as a lot more money than I, a journalist, will ever have and simply go about on my way.

Image Credits: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg / Getty Images

To most of us, the notion of, say, 18,000 people losing their jobs in one single decision from upper management is impossibly large. We — and I certainly include myself in this — can do a better job being mindful of the kinds of impacts these decisions have on an individual level. I know how painful being laid off is. I’ve been through it twice — I do work in publishing, after all. I know you can read a million LinkedIn posts and still not internalize that losing your job was not your fault. Some of us are just programmed to blame ourselves.

The first time I was laid off, it knocked me off track for a couple of years, frankly. Though I do firmly believe that you have to have gone through this experience to be able to exhibit compassion. I know this is obvious on the face of it, but losing a job in a bad economy means you’re looking for a job in a bad economy (in some cases, alongside hundreds of thousands of people with broadly the same skill set). It’s important to remember that when discussing layoffs at companies like Amazon, Microsoft and Google.

It’s also important to be honest about the degree to which success is a product of luck. That’s something that easily gets lost in the culture of rise-and-grind LinkedIn hustle-porn post platitudes. I’m sure reading the social media equivalent of an inspirational poster about how smart and successful some CEO thinks they are must have inspired someone at some point. But I don’t generally find it super useful.

I happen to believe there are some deep-seated issues that have let us get to a point where disrupting 10 or 20,000 lives is just the way it goes sometimes. But I’m also under no illusion that we’ll be able to address the root cause anytime soon. So, let’s start discussing the ways we can help one another, knowing that many of us have been through the process and, more than likely, will go through it again.

For me, it’s meant doing what I can to promote people who suddenly find themselves out of work. I’ll happily amplify them to my meager follower count. Sharing job openings is never a bad idea either. There’s a lot of talk about how the robotics community is, well, a community. Being part of a community means lending a hand when people are down. I would love to start a dialogue about the best ways to help in this current moment.

Starting next week, I’m going to feature a couple of companies that have open positions to fill in the robotics space. And drop me a line with the name of your company and how many roles you’re looking to fill. Hopefully we can get jobs for some of those impacted by all of this.

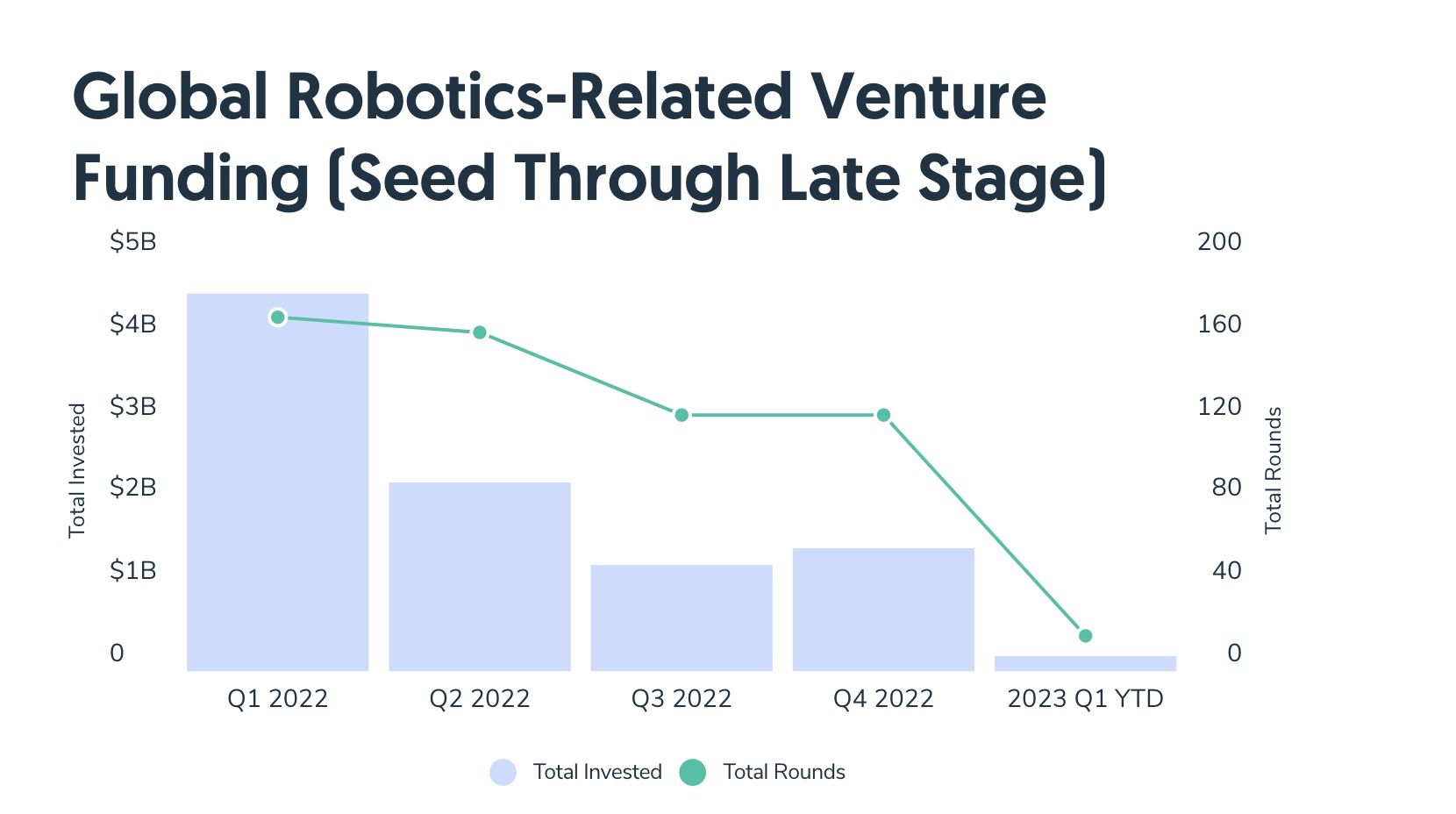

Image Credits: Crunchbase

A logical question in all of this is: How bad is bad? It’s a difficult thing to quantify, of course. Thankfully, some new figures just dropped from Crunchbase, collating some of the trends around robotics investments.

Here’s your headline: Investments in robotics startups was down 44% in 2022. That’s a lot. A lot, a lot — particularly for an industry that had so much forward momentum coming out of the pandemic. See the top line graph above for an easy visualization.

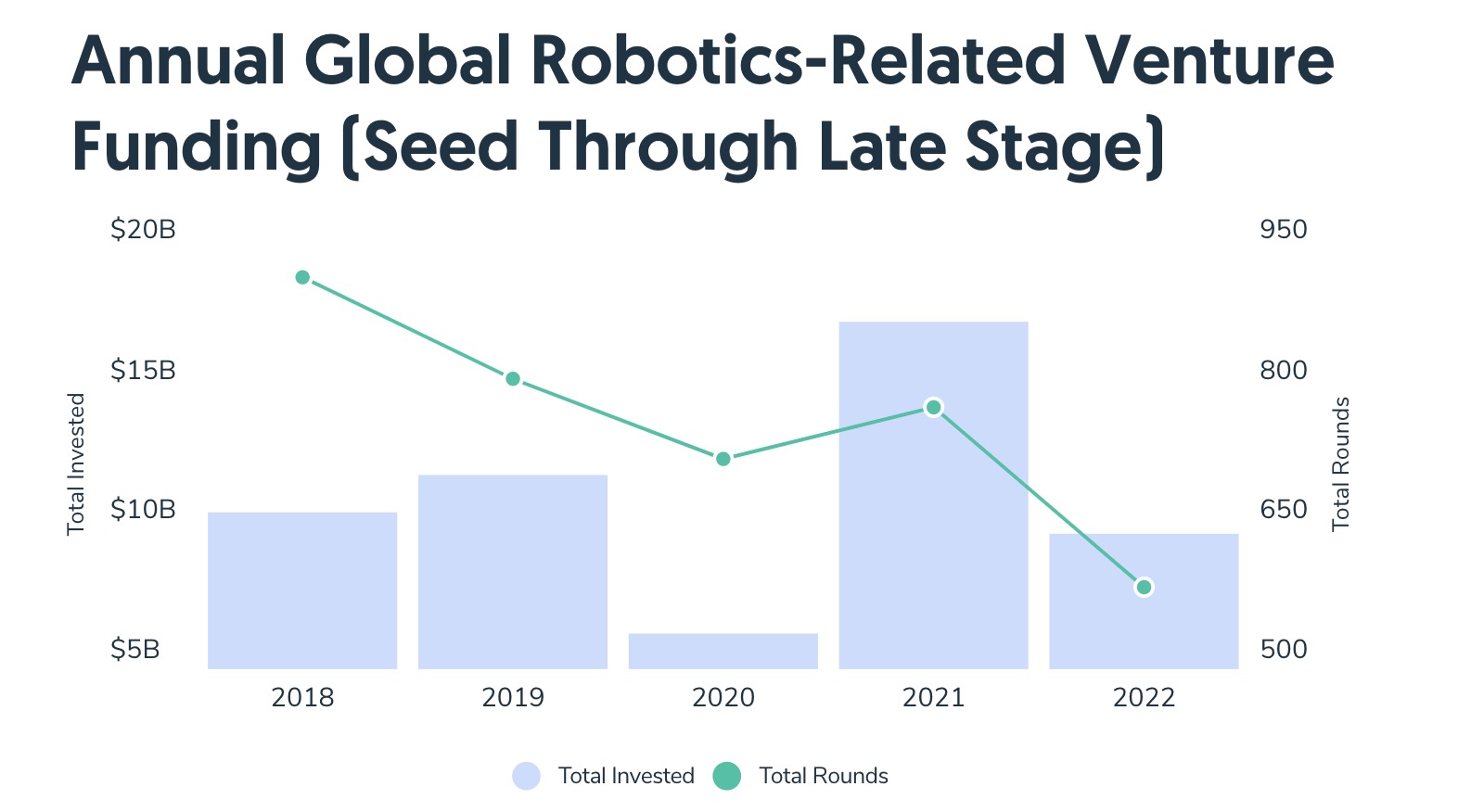

Image Credits: Crunchbase

Another thing you’ll immediately notice in this next graph: The 2022 bar is also lower than 2018 and 2019. In fact, it’s the second lowest in half a decade. Only 2020 was lower, and we all know what happened then. That was obviously an anomaly. The question, ultimately, is whether 2021’s record spend was an anomaly as well. Common thought — and I tend to agree — is no, on a long enough timeline. The economy will improve (though it’s an open question of how long that will take) and we’ll see a return to the trending upward growth.

I do believe the growth experienced in 2021 was a direct result of the fallout from the anomalous conditions that led to the 2020 dip, but I think it’s reasonable to expect a return to continued year-over-year growth.

The recession we’re currently facing will also have knock-on effects for the industry. One effect I’ve discussed previously is a potential increase in M&As. This makes local sense. Say you had a raise on the roadmap and suddenly your runway crumples beneath you. What’s the better outcome: closing the company or selling it to a potentially like-minded firm?

Image Credits: Roin/Built

I can’t speak to the specifics of Built’s acquisition of Roin, but I can say it’s another data point for what I anticipate will be a growing trend. As I noted in the piece, this one makes sense on the face of it. The two companies weren’t competitors, so much as complementary, as this deal effectively extends Built’s offerings to include concrete automation and the extremely fun term “shotcrete” (shooting concrete, basically).

“Since their founding, Roin’s team has pushed the boundaries of construction autonomy, which has created a unique expertise in our industry,” Built Robotics founder and CEO Noah Ready-Campbell said in a release. “With Roin joining Built, the combined teams will continue developing new autonomous construction applications and customers can expect to see robotic applications expanding beyond earthmoving.”

Image Credits: Kewazo

Construction is, of course, a prime target for automation. It’s massive, it’s extremely profitable and it checks off the three Ds (dull, dirty, dangerous) quite easily. This week, Munich-based Kewazo, which we had as a young early-stage startup at our TC Sessions: Robotics pitch-off pre-pandemic, just raised $10 million. The company’s Liftbot product is effectively an automated elevator for scaffolding.

“Despite already existing labor shortages, it became impossible for foreign workers to commute back to their home countries and come back,” Kewazo co-founder and CEO Artem Kuchukov told TechCrunch. “Many sites in Europe, the Middle East, and Singapore massively suffered from that, as a large percentage of their workforce simply wasn’t there anymore. That was a huge catalyst for construction automation, as companies began to look for ways to sustain their businesses without relying on an uncertain labor supply.”

Image Credits: Scythe Robotics

In spite of all the aforementioned slowdowns, I have seen fundraising starting to slowly ramp up after the holidays. Landscaping firm Scythe just announced a sizable $42 million Series B, bringing its total funding north of $60 million.

“The market has definitely taken a bearish turn,” co-founder and CEO Jack Morrison told TechCrunch of the round, “that committed climate VCs are well funded and actively looking for investment opportunities that urgently address the intensifying climate crisis we face.”

Image Credits: Cornell University

And finally, since this has been a heavy one, let’s close by looking at this soft robot from Cornell. It’s a fun exploration of how movement can be influenced through compliant actuators.

“We detailed the full complement of methods by which you can design these actuators for future applications,” says researcher Kirstin Petersen. “For example, when the actuators are used as legs, we show that just by crossing over one set of tubes, you can go from an ostrich-like gait, that has a really wide stance, to an elephant-like trot.”

Image Credits: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch

Like your Actuators nice and compliant? Subscribe today.

Then call them ‘robots’ by Brian Heater originally published on TechCrunch

Source : Then call them ‘robots’