I never thought much about my own family bloodlines and ancestry until we moved to Oklahoma in 2006. As I got to know teachers and school staff members in my role (at the time) working as an “education advocate” for AT&T, I learned that all public schools in Oklahoma have “Indian Education” programs and students qualify for these programs based on the percentage of their blood which corresponds to a federally recognized Indian tribe. In Oklahoma, that’s a list of 38 tribes. Tribal membership rules vary, and many have been modified, so “the blood percentage” required has been reduced in some cases which has allowed shrinking tribal rolls to expand. Membership in some tribes is tied to whether your ancestors registered on the “Dawes Rolls” between 1899 and 1907. While I certainly had thought about and been aware of racial differences and skin color throughout my life at different times (especially when I lived in Mississippi from 1978-80 and Mexico City from 1992-93) bloodline ancestry was a novel concept for me before 2006. My own learning about Oklahoma Indian tribes and tribal members has grown a little over the ensuing years, because of different relationships, projects, and job opportunities. I’m still embarrassed, however, about how very little I know (relatively speaking) about the respective histories and cultures of Oklahoma’s different Indian tribes. On October 6th, about a week ago, I had an opportunity to drive almost 500 miles from our home in Oklahoma City down to the Hill Country of Texas, and I stopped in a couple museums in Lawton, Oklahoma on the way. In this post, I’m going to reflect on some of the things I’ve learned in the past few weeks reading a book about Comanche tribal history, and how this “gave me new eyes” for my drive through historic “Comancheria” today.

In addition to being extremely ignorant of North American tribal history, I admit that in the past I have made the all-to-common mistake of viewing American Indian tribes as more monolithic (the same) than diverse and different. Just as it’s a huge mistake to speak of “Africans” instead of the unique and very different people who inhabit and originated from the continent of Africa, it’s also a huge mistake to regard ethnic or religious groups with a similar “broad brush.” Muslims and the Islamic world are far from monolithic. The same is true for American Indian tribes.

Although I grew up during part of my elementary school years living in Lubbock, Texas (1975-78) and returned to live in Lubbock from 1993 to 2006, my knowledge of the Comanche Indians was very limited. I heard a little about Quanah Parker and Ranald Mackenzie, but didn’t deeply contemplate or comprehend the ferocious violence of frontier in the 1800s during the decades preceding and following Texas “independence” and statehood in 1845. Despite periodic visits when we lived in Lubbock to their outstanding National Ranching Heritage Museum, and seeing the relocated frontier homes with shooting positions raised and gun ports open for fending off Indian attacks, I didn’t think deeply about the reality of that world until reading “Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History” by S. C. Gwynne (@scgwynne).

Some Oklahoma elementary students still re-enact and “celebrate” the Oklahoma land run of 1899. All three of our kids in Edmond Public Schools and Oklahoma City Public Schools did, Alex and Sarah at Chisholm Elementary in Edmond and Rachel at Quail Creek Elementary in OKCPS. I grew up (through 3rd grade) in a Texas elementary school learning about white heroes like Davy Crockett and Sam Houston. I learned and our 3 children predominantly learned in elementary school “a white man’s history” of the Comancheria frontier in the 1800s, and that meant quite a bit of important history and significant perspectives were left out.

“Karon Fitzgerald, Sarah and Shelly Fryer” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

“Sarah’s Land Run ”Family”” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

“3rd Grade Land Run Sooners and Boomers!” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

S. C. Gwynne‘s book “Empire of the Summer Moon” is remarkable and important for many reasons. One of these, as I already mentioned, is the factual way he documents the violence inside and along the borders of historic “Comancheria,” especially in the early to late 1800s. Those are the years heroically portrayed in Texas classrooms as the era of the Texas Revolution, the Republic of Texas, the Mexican American War, and the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo. History lessons from elementary and secondary classrooms in the United States blend naturally with Hollywood portrayals of “the old west” and the frontier, however, sometimes (or perhaps often) leaning toward a simplistic portrayal of these events where all the white settlers are “on the side of the Lone Ranger” and all the native peoples are unfortunate land squatters living on the wrong side of history. Of course, reality is far more complicated.

“79107 Lone Ranger Comanche Camp” (CC BY 2.0) by Brickset

Reading “Empire of the Summer Moon” gave me some important new insights into this era of history. The ferocity and savage violence of the Comanche Indians in opposing settlers on the frontier was as extreme as is possible for the human imagination. Certainly the beheadings and torture of westerners by ISIL / ISIS in the past five years has been horrific and terrible. It was actually exceeded in brutality, if one’s imagination is permitted to go this far, by the Comanches. I will not provide those details here, but S. C. Gwynne does in his book. If you take a time machine to 1830 into central Texas, and become or remain a Caucasian immigrant, it’s jarring to thinking about the “clear and present danger” in which you would be choosing to live if you remained there as a “settler.”

The story of Cynthia Ann Parker, the story’s role in defining the perceptions of Texas settlers and U.S. citizens more broadly, and the amazing as well as tragic juxtapositions of her life as the mother of Quanah Parker remain vital threads in the tapestry of history of Comancheria. Parker’s relatives were woefully naive and reckless in the unguarded way they chose to live before their fateful encounter with Comanches on May 19, 1836. After witnessing the deaths of many relatives and her own kidnapping by the Comanches, Cynthia’s subsequent adoption into a Comanche tribal group, marriage to Peta Nocona, role as mother to Quanah Parker, and eventual recapture by whites and functional imprisonment within white culture is one of those true stories which almost defies possibility. Because of this, a great deal of mythology (what we might call “fake news” today) was also associated with her. Anything I write here naturally risks oversimplification, and that is not my intention. Reading Gwynne’s record of this history was analogous to cracking open a geode of history for me about this era. It is complicated, multi-faceted, and extremely difficult to fully comprehend from my separated vantage point of 181 years.

“Geodes” (CC BY 2.0) by Trailmix.Net

One of the biggest turning points in my own thinking about our midwest North American history in the 1800s, catalyzed by Gwynne’s book, regards American bison herds and the inevitability of conflict between plains Indian tribes and white settlers coming from the east. I have often imagined that if I could travel in a time machine back to any era of history, I would go to the great plains of North America before the slaughter of the bison herds in the late 1800s. The sight of literally millions of bison roaming wild and free on the open plains of our continent would have been an awe inspiring sight to behold. While some people romanticize about the wolf in North America defining “wild,” or even the historic range of grizzly bears, it’s the American bison which has captured my imagination like no other creature on our planet.

“Bison in Yellowstone” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

Before reading “Empire of the Summer Moon” I had read and heard about the inevitability of conflict with the plains Indians of America, and the necessity of eliminating the wild herds of bison to fully defeat the plains Indians, but those lessons did not sink into my own understanding of history very deeply. Gwynne’s historical narrative makes it abundantly clear to me that in the grand course of history, these outcomes were inevitable.

Interjecting my own opinions into the historical record of the lower great plains in the 1800s is perhaps perilous, for as with all normative judgements about historical events I have limited access to facts on the ground and must rely on the observations and interpretations of others. That said, however, it definitely strikes me as tragic and unfortunate that the United States government repeatedly broke so many “treaties” which it negotiated with native people, including the plains Indians. As Gwynne recorded, after agreeing to move to an Oklahoma reservation, the U.S. government decided to change the terms of its treaty with the Comanche. Instead of permitting the tribe to own and manage (leasing to cattlemen for a handsome profit) vast swathes of land, Congress passed The Dawes Act of 1887. This permitted the U.S. government to “allot” previous lands granted to Indian tribes to individual Indians and families, and also to white settlers. It served to further impoverish Indian tribes and individual Indian leaders (like Quanah Parker) and further advance the white man’s mandate to native tribes to give up their way of life and “become civilized.”

The Comanche Indians in the early to mid 1880s were, in many ways, a stone age civilization which came into abrupt and violent conflict with modernity. In the parlance of Alvin Toffler, they were a first wave civilization coming into conflict with a second wave civilization equipped (by the late 1880s) with the lethal, advanced technology of industrialization. I had not known Comanches originally came down from the Wind River Canyon area of Wyoming, and were part of the historic Shoshone Tribe. Thanks to a unique confluence of factors, they acquired and adopted their nomadic way of life to the wild Mustang horse, and became one of the post potent and fearsome pre-industrial military powers in history. Their horse-powered ferocity and capabilities remind me of the Mongols as described in amateur historian Dan Carlin’s series “Wrath of the Khans.” It was both the adaptation of military tactics which mimicked the Comanche, utilized in the early days of the Texas Rangers and later by U.S. Army General Ranald Mackenzie, along with the technological advances of the repeating revolver and rifle (thanks Samuel Colt) which finally led to the end of free-ranging plains Indians in Texas and elsewhere in the American great plains.

I may never look again on a full moon the same after reading “Empire of the Summer Moon.” According to Gwynne, because the Comanche preferred to go on raiding trips at night by the light of the moon, Texas settlers began to call the full moon the “Comanche Moon.” Imagining the fear which justifiably must have seized hold of thousands of early Texas pioneers and settlers before the Comanche were finally forced to stay in reservations in Oklahoma stretches my mind.

“Nightime in the Wichita Mountains, Oklahoma” (CC BY 2.0) by jonathanw100

Of course we can’t say for certain what our opinions and actions would have been if we lived in a particular era of history rather than our present, since the factors defining our allegiances and loyalties would have played crucial roles and can’t be extrapolated. It’s impossible to say with certainty if I would have had the risk-welcoming disposition to leave the relative safety and predictability of the east for the danger and opportunities of the American west in the 1800s. If I had that disposition, however, and was a white pioneer, it is easy to imagine myself taking a racially defined side in the violent conflicts of the frontier. Returning to my original reflections about not having thought a great deal about the important role of bloodlines before moving to Oklahoma, these are relatively novel thoughts for me. Because of the time of my birth in the course of history, I have not had to make choices about “sides to be on” largely defined for me by the color of my skin and my own ancestors.

“White Pioneers Depicted in the July 2017” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

Driving south from Oklahoma City almost 500 miles to Hunt, Texas, about an hour west of San Antonio last Friday, I was thinking about many of ideas as I passed through historic Comanche reservation lands as well as Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in Lawton. There is a large Comanche Casino now in Lawton, and the large Kiowa Casino just north of the Red River and Wichita Falls, Texas, had more meaning for me as Gwynne’s book had given me a little more insight into the history and interactions of the Kiowa with early white settlers as well as the Comanche.

“Trek Across Comancheria” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

One of the things I thought about the most on this trip was the IDENTITY of men in the Comanche Tribe, and how that identity was almost completely obliterated (by tragic necessity) by the collision of cultures which happened in the 1800s on the southern great plains. To be fair and egalitarian, I probably should have thought just as much about the cultural identity and crisis for Comanche women, but since I’m a guy, I was thinking more about the men.

“Trek Across Comancheria” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

One of many things I learned in “Empire of the Summer Moon” was that Comanche men in the pre-reservation 1800s had two primary roles in their tribe and family: to hunt bison and go protect their family. Women did virtually all of the work butchering meat, doing camp chores and raising children. By the 1800s, the Comanches were entirely a “horse people,” defined by their relationship to and use of horses. Wealth for the Comanche, as with other plains tribes, was mostly defined by possession of horses. It seems crazy today to imagine that the U.S. Army and U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, proxies for the will of the U.S. Government on the plains, literally told and expected Comanche men moved onto an Oklahoma reservation to “become farmers.” In the history of humanity on our planet, has a more difficult cultural mandate ever been placed on one civilization by another?

“Comanche National Museum and Culture Center” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

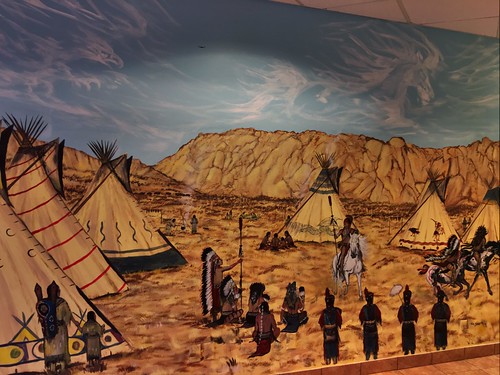

Thinking about these identity issues, last Friday I stopped for about an hour at the Comanche National Museum and Culture Center in Lawton. The museum is small and modest. Imagining the vast numbers of horses once possessed by the Comanche tribes, who continue to use the moniker “Lords of the Plains,” it was sad yet perhaps predictable to see statues of a single horse and a single bison outside the museum’s entrance.

“Lone Horse outside the Comanche National” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

“Lone Buffalo outside the Comanche Nation” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

My thoughts and emotions seeing these statues and touring through the Comanche Museum were different than they would have been three months ago, before I read “Empire of the Summer Moon.” I was more aware than ever of history which had transpired, but also that the Comanche people live on today as a surviving tribe from the cultural genocide promulgated by conflated forces in the late 1800s including Texas settlers and the U.S. military. Before reading Gwynne’s book, I had a much shallower appreciation for how the Comanche had ferociously served as a buffer between the nation and people of Mexico and the dreams of Manifest Destiny sown and nurtured by thousands of white people living and migrating from eastern lands. According to Gwynne, the Comanche turned back the advances of the French, the Spanish, and for many years the Americans (the United States) in “civilizing” the great midwest.

“Trek Across Comancheria” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

Driving across large swathes of Texas as I have over the past twenty years, traveling from Lubbock to Austin or Oklahoma to San Antonio for different conferences and family trips, I’ve often wondered why there are not any Indian tribes in Texas? I knew that the Texas pioneers killed or drove off all of the Indians, but why did this happen in Texas when in some other parts of the midwest tribes continued to live on reservations and exist as a people? Gwynne provided the answer in “Empire of the Summer Moon.” The conflict lines between the Comanche and the Texans were so stark, and were so absolute, that there literally was no room for compromise or co-habitation. This is why the Comanche hated Texans with such a vengeance, and vice versa. Gwynne shares a story of Charles Goodnight, who encountered Quanah Parker and other Comanches on “his” newly acquired property in Palo Duro Canyon, after the Comanche “reservation era” had begun, and relates how Goodnight eventually convinced the Indians he was from Colorado and not a Texan. If he had not been successful, they might have killed him for simply being from Texas.

I’m definitely not condoning every act of frontier violence promulgated against the Comanche during the days of the frontier, but am saying Gwynne’s recounting of this era of history in his book gave me a much deeper and nuanced understanding of why Texans did not create or allow any reservations for Indians within the boundaries of their former nation and current state. This conflict and history wasn’t simple, it wasn’t pretty, and it certainly isn’t easy to understand and accept almost two hundred years later. It was, however, in my current estimation an inevitable “clash of civilizations” whose outcome was both predictable and inevitable based on the march of technological advances.

A final image and reflection I’ll share comes directly from the Comanche National Museum and Culture Center last Friday. It’s both understandable and expected that the written narratives as well as limited multimedia exhibits in the small museum do not address the ferocity and violence of the Comanche people’s conflict with Texans in the 1800s. Just as Gwynne relates that Quanah Parker “wisely” did not talk publicly about his campaigns against white settlers as well as the U.S. military once the Comanche reservation era began, it’s reasonable that the current Comanche national museum does not focus on the violent details of those conflicts either.

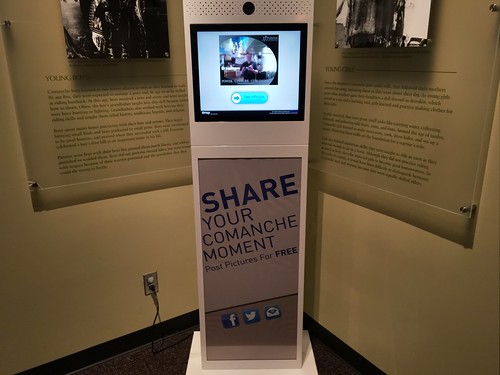

It seemed rather jarring, however, to be by myself in the Comanche national museum last Friday, and see a self-serve photo selfie station with the encouraging caption, “Share Your Comanche Moment.”

“Trek Across Comancheria” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

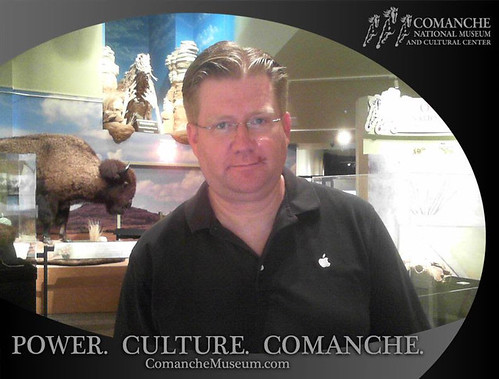

I did, perhaps predictably, take a photo and check the tick box giving permission for my image to be shared publicly on the contracted social media website used by the tribe. I couldn’t bring myself to smile for the photo, the weight of too much violent history and conflict was filling my mind.

“Wesley Fryer’s ”Comanche Moment”” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

Take a moment to browse through the most recent additions to this social media sharing station from the Comanche Cultural Center. Today as I miraculously view these from 20,000’+ MSL on board a cross-continent flight from New York City to Dallas, Texas, all the faces I see are white. And that is good: I’m glad more people (hopefully of all races) are taking time to learn more about the Comanche people, their history and their culture.

I couldn’t and can’t help thinking, however, what a different “Comanche Moment” most of the white settlers in Texas would have shared in 1836, 1850, or 1877… to randomly pick a few years, if a social media selfie sharing booth had been available anywhere in northern or central Texas. This was and is a moment of historic cognitive dissonance, as the technologies of “modernity” continue to encounter the realities and perceptions of history.

If “becoming farmers” seemed like a ludicrous and almost impossible idea for Comanche Indians in the late 1800s, what challenges to cultural identity are not only present today for living native people in the United States but also for people of other races? The relentless march of technological advances have brought mechanization to the farmer’s “allotment” of the 1887 Dawes Act. We are living now into an era where cities have a magnetic draw for literally millions around the globe, and our rural areas continue to depopulate as cities swell ever larger. Thinking about the challenges Comanche Indians faced in the late 1800s and early 1900s to assimilate into “white society,” the imminent challenges truck drivers will face as self-driving cars and trucks go mainstream in the next decade seem paltry by comparison. Truck drivers “only” face the need to retrain for a new job, not reorient their entire cultural identity and that of their nation.

“Trek Across Comancheria” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

One last fact before I close this lengthly post and reflection. I learned from the Comanche museum docent that the tribe currently has about 17,000 members. If I’m remembering correctly from Gwynne’s book and other articles I’ve read in past weeks, this is up from a low of about 1500 members at one point. Today’s English WikiPedia article for the Comanche Nation estimates post-contact membership in the late 1800s at approximately 45,000. The docent explained that today, anyone with at least one-eighth Comache blood is or can become a tribal member. This is specifically outlined in the online version of the Comanche Nation’s Constitution. Again, the role and importance of blood and anscestry wasn’t something I thought a lot about before moving to Oklahoma. I’ve definitely been thinking a lot more about this in the past few months.

I will close this post with two images which further juxtapose technological modernity with the history and ongoing story of the Comanche people and “the rest of us” in the southern great plains.

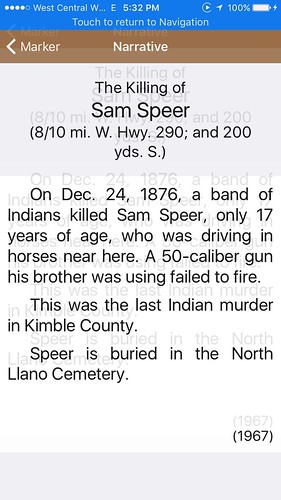

Two Fridays ago as I drove 480 miles from my home to Mo Ranch near Hunt, Texas, I downloaded Gregory Moore’s “Texas Historical Marker Guide” app on my iPhone shortly after crossing the Red River and entering the geographic boundaries of Texas. As a result, throughout my journey down through historic Comancheria, I read and heard about historic encounters between early Texas settlers and the native people who had lived there first like this. As a storychaser and student of history, it’s a wonderful thing when technology can bring both historic context and stories to a geographic location. I’m thankful to live in our “modern age” when this is possible, but of course for MANY, MANY other reasons which my enlarged understanding of history helps me appreciate.

“Trek Across Comancheria” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

On that recent journey across historic Comancheria, in addition to stopping at the Comanche Cultural Center I also filled my car with gasoline and purchased lunch at the Comanche Travel Center just north of the Red River. On the wall of the travel center, the official logo of the “Comanche Nation: Lords of the Plains,” are juxtaposed on an image gallery with photos of South American coffee beans and filled coffee cups.

We live in times of rapid change, but I wonder if the level of cultural change with which we’re confronted in 2017 approaches the stark scale faced by members of the Comanche Tribe in the late 1800s? I don’t think it does. Stone age meets second wave industrialization and pioneer settlement is a much bigger contrast to, “you grew up with a Sony Walkman and now you’ve got a supercomputer in your pocket.”

Add “Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History” by S. C. Gwynne (@scgwynne) to your future reading list. It’s guaranteed to give you a rich platter of food for thought. And count your blessings. I’m immensely thankful “sharing my Comanche moment” means something completely different to me than it would have to Ranald Mackenzie. His name and historic contributions to our nation and military history, by the way, deserve more attention than that accorded to George Armstrong Custer. If you’re not sure why, get to reading and researching! You’ve got some important learning waiting for you in the annals of North American military history.

“Comanche National Museum and Culture Cen” (CC BY 2.0) by Wesley Fryer

If you enjoyed this post and found it useful, consider subscribing to Wes’ free, weekly newsletter. Generally Wes shares a new edition on Monday mornings, and it includes a TIP, a TOOL, a TEXT (article to read) and a TUTORIAL video. You can also check out past editions of Wes’ newsletter online free!

Did you know Wes has published several eBooks and “eBook singles?” 1 of them is available free! Check them out! Also visit Wes’ subscription-based tutorial VIDEO library supporting technology integrating teachers worldwide!

MORE WAYS TO LEARN WITH WES: Do you use a smartphone or tablet? Subscribe to Wes’ free magazine “iReading” on Flipboard! Follow Dr. Wesley Fryer on Twitter (@wfryer), Facebook and Google+. Also “like” Wes’ Facebook page for “Speed of Creativity Learning”. Don’t miss Wesley’s latest technology integration project, “Show With Media: What Do You Want to CREATE Today?”

Source : Reflections on Comancheria, Identity and Frontier Terrorism