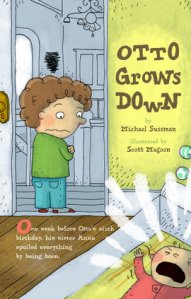

I first met author Michael Sussman when I reviewed his debut picture book OTTO GROWS DOWN, illustrated by Scott Magoon. I LOVED IT! In fact, OTTO remains one of my favorite picture books of all time, and I often refer to it when teaching humor and picture book workshops.

Michael wrote me a lovely thank-you email and we became fast friends and critique partners. He went on to write novels, but now he’s back to picture books and his latest, DUCKWORTH THE DIFFICULT CHILD, is creating a kidlit buzz for its retro vibe and dark humor.

Michael, I’m so thrilled to have you back in picture books! It’s been a while since OTTO GROWS DOWN!

Michael, I’m so thrilled to have you back in picture books! It’s been a while since OTTO GROWS DOWN!

OTTO is the boy who wants his little sister to disappear, and she does. In DUCKWORTH, he himself “disappears,” but he didn’t want to!

For fun, can you compare and contrast OTTO and DUCKWORTH as characters?

What a wonderful question!

First off, I want to thank you, Tara, for all your help in promoting OTTO GROWS DOWN, and for being such a wonderful critique partner for so many years.

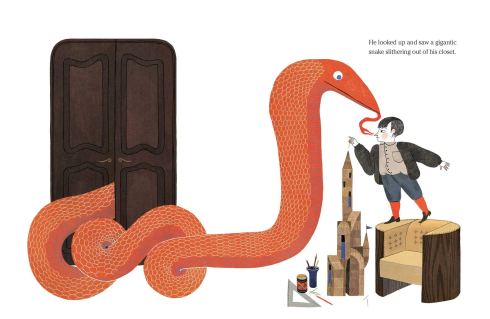

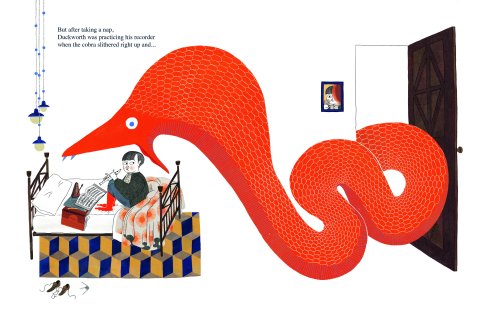

To my mind, what links Otto and Duckworth is that they both face dire circumstances which they must overcome without any help whatsoever from their parents. Unbeknownst to his mom and dad, Otto is trapped in backward time and will disappear altogether if he doesn’t figure out how to return to the present. Duckworth’s parents are oblivious to the fact that he has been swallowed by an enormous cobra, and he is left to his own devices to escape from inside the snake.

In contrast to Duckworth, Otto has a loving family, but must come to terms with an interloper: a new baby sister. In order to overcome his understandable resentment and animosity toward Anna, he must grow up and become aware of his burgeoning love for his sibling.

Duckworth is an only child and is faced with a far more difficult predicament: narcissistic parents who are utterly oblivious to his needs and concerns. Although Duckworth is as successful as Otto at conquering his life-and-death dilemma, the ending of his story remains bittersweet, as he is still stuck with woefully inadequate parents.

Poor Duckworth, stuck with oblivious parents who seem like the despicable adult characters in a Roald Dahl story. DUCKWORTH, as a whole, has a very nostalgic energy, like a picture book from days long ago. Did you get any inspiration from “dark humor” authors of the past?

DUCKWORTH is my homage to the classic picture book, THE SHRINKING OF TREEHORN, by Florence Parry Heide and Edward Gorey, soon to be a motion picture directed by Ron Howard. I love the dark humor of Gorey, Dahl, and William Steig’s SPINKY SULKS.

DUCKWORTH is my homage to the classic picture book, THE SHRINKING OF TREEHORN, by Florence Parry Heide and Edward Gorey, soon to be a motion picture directed by Ron Howard. I love the dark humor of Gorey, Dahl, and William Steig’s SPINKY SULKS.

What is it about those dark humor books that you admire? Why did you want to pay homage to them?

I guess I just like dark humor in general, and have featured it in both my picture books and novels. Dark humor presents unpleasant and taboo aspects of life in a satirical manner, taking the edge off and relishing in the absurdity of the human condition. In stories, it allows authors to address potentially painful topics—such as sibling rivalry in OTTO and poor parenting in DUCKWORTH—in a manner that’s less threatening and more enjoyable than a straightforward or didactic approach.

I was also eager to riff on THE TREEHORN TRILOGY because I felt it was under-appreciated and falling into obscurity. Now, thanks to me and Ron Howard, it’ll be rediscovered!

Let’s talk about the illustrations by Júlia Sardà. They are dark and mysterious, with a retro European surrealist vibe. (Maybe I think that because the mother looks like Salvador Dali?) The gorgeous cinnabar of the cobra jumps out and bites you.

The art takes full advantage of perspective—I love the illustration of Duckworth in the serpent’s stomach, surrounded by floating items the cobra has swallowed.

Is the art what you had imagined?

Júlia Sardà’s illustrations are spectacular, and way beyond anything I could have imagined or hoped for. Her style, sense of composition, and attention to detail are extraordinary, and perfectly complement the story. The illustrations are so striking that I actually became concerned that they’d overshadow the text, and convinced my editor—the wonderful Emma Ledbetter—to switch to a more dramatic font, and make use of drop-down letters to highlight the first word on some pages.

I was initially surprised by some elements of the artwork that diverged from what I’d expected. The snake is WAY bigger than I’d anticipated, and I think that was a brilliant choice. The mother’s face, body, and attire are quite masculine-looking, which bothered me at first, but I think this allows the parents to be presented as a single unit, which fits the story. (Not to mention that the mother, as I wrote her, is utterly devoid of maternal concern!) I expected Mr. and Mrs. Snodgrass, the neighbors, to look British, but they are decidedly Russian in appearance. Finally, Duckworth looks more peculiar than I’d envisioned him, but I’ve grown to like that. Initially, he looked far too old, but Emma and I convinced Júlia to make him younger.

So there were some changes and edits to the art. What about to your original manuscript? Did anything turn out differently than the version you submitted?

Initially, the boy’s name was Bowlby. I wanted an odd name, to parallel Treehorn, and I think I unconsciously selected Bowlby because of the famous British psychologist, John Bowlby, who did pioneering work on maternal deprivation. But Emma wasn’t wild about the name, so I made a list of unusual monikers, and the two I liked the best were Duckworth and Digby. My son, Ollie, preferred Duckworth, which Emma liked as well, so I used Digby for the name of Duckworth’s cousin.

Ha, Bowlby is a funny name, but I do like Duckworth far better!

In giving a workshop on humor recently, I talked about “superiority humor” and how feeling superior to someone else is a cause of laughs.

In DUCKWORTH, the child feels superior to the parents, and I think your reader will also feel superior to the Mr. & Mrs. Was that a deliberate decision to make the adults in the book so hapless?

Superiority theory states that we laugh at the misfortunes and shortcomings of others because it makes us feel better about ourselves. And indeed, a portion of the story’s humor stems from seeing the pompous stupidity and ineptitude of Duckworth’s parents. The vast majority of parents who read the book to their kids will be able to pat themselves on the back, thinking I may have my faults, but I’m a far better parent than these hapless twits.

But I think that Incongruity theory, the notion that humor derives from the enjoyment of a perceived or imagined incongruity, is a better fit here. The discrepancy between Duckworth’s desperate plight and his parents’ haughty indifference and self-preoccupation, is amusing.

Surrealist or absurdist humor is also at play, in that the story presents a ridiculous situation that is impossible to take seriously, and the obliviousness of Duckworth’s parents is exaggerated to the point of absurdity.

Well, I think you use all those forms of humor brilliantly.

I’ll close our interview with how I typically begin…

You know I host Storystorm to inspire writers. So what inspired DUCKWORTH?

Well, I was suffering from writer’s block at the time, so I resorted to my patented Whack-a-Plot titanium mallet, which I invented for your 2010 PiBoIdMo (forerunner to Storystorm). Within seconds of regaining consciousness, the story came to me in a flash.

titanium mallet, which I invented for your 2010 PiBoIdMo (forerunner to Storystorm). Within seconds of regaining consciousness, the story came to me in a flash.

Seriously, folks, the story was inspired by a visual image, which is unusual for me since I have aphantasia, a condition where one does not possess a functioning mind’s eye and cannot voluntarily visualize imagery. (I’m not making this up.)

One summer evening, while taking a stroll, an image passed through my mind of a snake that had swallowed a child. As I imagined the bulge working its way down the length of the serpent, it struck me as a compelling (if somewhat macabre) basis for a picture book. I recalled a similar image from The Little Prince, but when I returned home, I discovered that the prince’s drawing was of a boa digesting an elephant. (Although, as the prince notes, grown-ups all thought it was a picture of a hat.)

I worried that my concept might be too scary for young children, unless I made it a funny story, so I decided to model the tale on THE SHRINKING OF TREEHORN.

Michael, I think you’ve created a new classic! Thank you for chatting with me about DUCKWORTH!

Blog readers, Simon & Schuster is giving away 2 copies of DUCKWORTH THE DIFFICULT CHILD.

Just leave one comment below to be entered in the giveaway.

Two random winners will be selected in mid-August.

Good luck!

Abandoned by a cackle of laughing hyenas, Michael Sussman endured the drudgery and hardships of a Moldavian orphanage until fleeing with a traveling circus at the age of twelve. A promising career as a trapeze artist was cut short by a concussion that rendered him lame and mute. Sussman wandered the world, getting by on such odd jobs as pet-food tester, cheese sculptor, human scarecrow, and professional mourner while teaching himself the art of fiction. He now lives in Tahiti with Gauguin, an African Grey parrot. Visit him at MichaelSussmanBooks.com.

Abandoned by a cackle of laughing hyenas, Michael Sussman endured the drudgery and hardships of a Moldavian orphanage until fleeing with a traveling circus at the age of twelve. A promising career as a trapeze artist was cut short by a concussion that rendered him lame and mute. Sussman wandered the world, getting by on such odd jobs as pet-food tester, cheese sculptor, human scarecrow, and professional mourner while teaching himself the art of fiction. He now lives in Tahiti with Gauguin, an African Grey parrot. Visit him at MichaelSussmanBooks.com.

Source : DUCKWORTH is Worthy of its Dark Humor Predecessors (plus two giveaways)