Looking back on my reading list, I was shocked that the year began with Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. I re-read it in January because I was writing about Greta Gerwig’s film adaptation of the novel. Does anything seem more unlike the doomscape of 2020 than the joy and optimism of Gerwig’s Little Women? To be honest, rereading Little Women was a bit of a slog, especially the first half, when Marmee gives so many lectures. But the second half, which was originally published as a second volume called Good Wives, was unexpectedly modern, with many scenes devoted to the business of writing and publishing. A few weeks after I read the book, I watched the first two episodes of My Brilliant Friend on HBO and was surprised to see the girls passing Little Women back and forth — a detail I had forgotten from Elena Ferrante’s novel. But it makes perfect sense. The book is a talisman for girls who want to be writers.

I never finished watching My Brilliant Friend. It was a year of not finishing a lot of things — TV shows, books, manuscripts. At the beginning of the pandemic, I was drawn to dense histories: Russell Shorto’s The Island at the Center of the World, Adam Higginbotham’s Midnight in Chernobyl, and Tony Judt’s Postwar. I guess I was trying to get some perspective. But I never finished any of them.

What I did get through were memoirs. Before the pandemic started, I read Ruth Reichl’s Save Me The Plums, about her time at Gourmet magazine, which was abruptly shut down by Condé Nast in 2009 — one of the many casualties of the financial crisis. I enjoyed it so much that I went back and read Reichl’s previous memoir, Garlic and Sapphires, about being a restaurant critic for The New York Times. If Save Me The Plums felt like a nostalgic look back at the magazine world, Garlic and Sapphires felt retro to an almost Mad Men-degree, taking place in a quiet, internet-free world. In contrast to today’s never-ending news cycle, Reichl’s busy, deadline-driven life actually seemed pretty chill. If someone didn’t like her column — and they often didn’t — her editor got letters in the mail. Can you imagine? Me neither. And I grew up in that world.

I followed Reichl’s memoir with Cat Marnell’s How To Murder Your Life, which I thought was going to be an addiction and recovery story, but turned out to have more in common with Little Women and Save Me The Plums. Marnell’s memoir is as much about becoming a writer and working in the magazine business as it is about drug use and addiction. She and Reichl both show how precarious print media always was, with magazines getting by on corporate advertising budgets and a labor force of young people willing to survive on perks — a business model that proved to be completely unsustainable after the arrival of digital and social media. Their memoirs aren’t marketed as works of history but they both captured the end of an era.

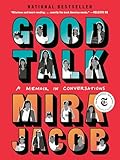

As New York locked down, I read Good Talk by Mira Jacob, a graphic memoir about talking to your kids about race and identity and family and other complicated subjects. It’s the kind of memoir that makes you feel close to the author, and the whole time I was reading, I was wondering how Jacob and her family were doing in the pandemic — I knew they lived near me, in Brooklyn. Shortly after finishing it, I received an answer to my vague worries in the New York Times in the form of a fresh comic from Jacob. They left the city.

In May, I joined the exodus and relocated to the suburbs of New Jersey. As we drove back and forth to New Jersey, looking for a new apartment, we kept our kids entertained with an audio book of Laura Ingalls Wilder‘s Little House in Big Woods, narrated by Cherry Jones. Children weren’t allowed inside the empty apartments, due to COVID restrictions, so my husband and I took turns looking while the other waited in the car, listening to Cherry Jones describe all the delicious foods Ma was making. Little House in Big Woods turned out to be the perfect pandemic read, since Laura and her family are basically in quarantine all the time, with no one ever coming to their isolated homestead and Ma always undertaking elaborate baking and craft projects.

I hate unpacking. It feels so anti-climatic after you’ve done all the work of packing. After we moved, I had a procrastinator’s appetite for reading and tore through two West Coast memoirs: Miss Aluminum by Susanna Moore and Stray by Stephanie Danler. Both were haunted by trauma and tinged with glamour. I read Sea Wife by Amity Gaige, which was also haunted by trauma — and by the dream of escape: escape from marriage, escape from land, escape from domestic life. It was a good late-night read.

In July, our library started doing curbside pick-up, so I ordered Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley after re-watching the movie on Netflix. I didn’t think the book could be any better than Jude and Gwyneth bathed in the golden light of Southern Italy, but I found a novel that was darker than the movie, and more coherent. In the movie, Ripley kills in passionate moments, out of jealousy or fear; in the book, he’s calculating, killing out of self-interest. He wants a good life for himself, with nice clothes, and nice furniture, and good things to eat and drink. He doesn’t take pleasure in murder but he’ll do what he has to do to maintain his standard of living. As soon as I finished the first Ripley novel, I started the second one — Ripley Underground — which wasn’t as good but delivered the same ice-cold truth. There was a moment when I was convinced that I was going to spend the rest of 2020 reading Ripley novels, because they seemed like the only thing that could capture the chilling superficiality of the Trump Administration, but when I started the third one I realized I’d had my fill — for now. It’s a perverse comfort to know that Ripley’s always there for me, wearing his elegantly tailored clothes and sipping Pernod.

After Ripley, I craved emotion. I read a bunch of first-person novels, one after the other: Writers & Lovers by Lily King, Want by Lynn Steger Strong, Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld, Weather by Jenny Offill, Sag Harbor by Colson Whitehead, and What Are You Going Through? by Sigrid Nunez. Nunez’s book was the one that really got me, and the one I would recommend for this year in particular. It’s a book about trying to control death, but you can’t, the most you can do is acknowledge the suffering of other living things. It’s a heavy insight but Nunez delivers it lightly; the novel feels spacious and conversational and there’s a scene with a cat that I want to spoil but won’t. I’ll just say that the scene — and the novel — is a worthy companion for the dark winter ahead.

More from A Year in Reading 2020

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The post Year in Reading: Hannah Gersen appeared first on The Millions.

Source : Year in Reading: Hannah Gersen