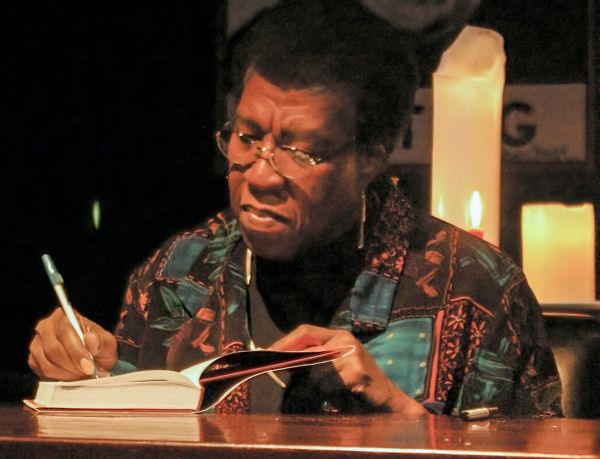

“Who am I?” reads an old jacket cover of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, “I am a forty-seven-year-old writer who can remember being a ten-year-old writer and who expects someday to be an eighty-year-old writer. I am also comfortably asocial, a hermit in the middle of Los Angeles. A pessimist if I’m not careful, a feminist, a Black, a former Baptist, an oil and water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty, and drive.”

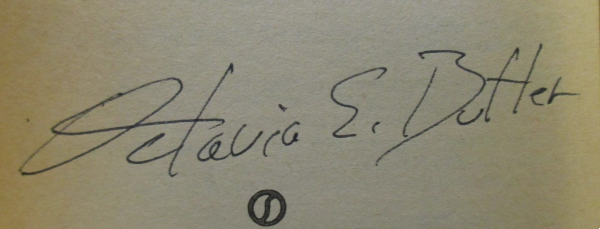

This famous description is catchy, but it barely scratches the surface of who Butler was. Her legacy as the first Black woman science fiction writer precedes her, but she was never too fond of labels. As her many interviews and novels show, there was a lot more to her than a simple by-line.

Octavia Butler’s Early Life

Octavia Estelle Butler was born to Laurice and Octavia M. Butler (née Guy) in Pasadena, California, on June 22, 1947. Her father passed away when she was still a toddler and young Butler was raised primarily by her mother and grandmother. She went by Estelle to everyone except her mother, who lovingly called her “Junie.”

Her mother was a domestic worker who cleaned houses for a living. She would sometimes take Butler with her to work, and because she wasn’t allowed in, Butler would wait in the car. On the few exceptions of these days, Butler would follow her mother inside. Sometimes she would hear people speak about her mother in disrespectful ways. As a child, the anger and humiliation she felt on behalf of her parent were directed at her mother, for not standing up for herself, rather than the people who insulted her.

“I will never do what you do,” Butler recounts telling her mother in an interview with Daniel Burton-Rose, “What you do is terrible.” At the time, her mother hadn’t said anything, but looked hurt. Years later, Butler came to regret her words, “I carried that look for a number of years before I understood it…I didn’t have to leave school when I was ten, I never missed a meal, always had a roof over my head, because my mother was willing to do demeaning work and accept humiliation.” Later, it would be people like her mother who Butler saw as heroes and who would inspire her to write her most famous novel, Kindred.

Her mother would often read to Butler from the Bible, and after Butler turned 5, she would read to her mother. Butler has fond memories of this time. Her mother was passionate about her daughter’s education. She would bring home armloads and boxes of discarded books from the houses she cleaned, all for Butler to read. At 6 years old, Butler asked her mother for a library card after an inspiring school trip. Her mother, surprised but happy, gladly agreed.

Butler was the last of five children, and the only one who survived. She had four older brothers, but they all passed away before she was born. Butler often wondered what it would have been like for her, had her siblings survived. Since she didn’t have that, she found solace in reading and books. Moreover, she created a place for herself in her own mind. She had been telling herself stories since she was 4 years old. At 10, she began writing them down because she was afraid she would forget them. She had a little notebook and would write in it with a no. 2 pencil. By 13, she was sending her stories out to publishers.

Writing is all I really ever wanted to do. Once I discovered it, I found that I enjoyed it and my mother just made a remark accidentally when I was about ten. She saw me writing and I told her I was writing a story and she said ‘Well, maybe you’ll be a writer.’ And at that point I had not realized that there were such things as writers and it had not occurred to me how books and stories got written somehow. And in that little sentence, I mean, it was like in the cartoons where the light goes on over the guy’s head. I suddenly realized that yes, there are such things as writers. People can be writers. I want to be a writer.

Octavia Butler, Conversations with Octavia Butler

Launch of Writing Career

When asked about what inspired her to start writing science fiction — and this happened in almost every interview — Butler would talk about how she was watching the movie Devil Girl from Mars, and had thought, “Gee, I can write a better story than that.” So she switched off the TV and began writing a story. Since the movie she had watched had been science fiction, she tried to write a story that was science fiction, as she understood it then.

Butler studied at Pasadena City College and earned an associate’s degree in 1968. The following year, Butler was admitted to the Open Door Program of the Screen Writer’s Guild, where she took a class by Harlan Ellison. Ellison became Butler’s friend and mentor and encouraged her to attend the Clarion Science Fiction Writer’s Workshop. The workshop at Clarion, Pennsylvania, was an important step in Butler’s career in many ways. It was where she met Samuel R. Delany, another mentor. It was her first time stepping foot out of California, and it was where she made her first sales. She sold her first short story, “Crossover,” to the Clarion Journal, where it was published in 1970. Another story, “Childfinder,” was to be included in Last Dangerous Visions, a volume of short stories collected by Ellison that went unpublished.

For the next five years, Butler didn’t publish a word. When asked to describe those early years of her writing career, Butler says, “Frustrating. Frustrating. During those years I collected lots of frustration and rejection slips.” She took a train of jobs to support herself: washing dishes, sweeping floors, going through warehouse inventory, sorting potato chips, and so on. During this entire period, she remained dedicated to her craft, getting up at 2 or 3 a.m. to write. Then Butler was laid off from another job two weeks before Christmas, 1974, and she decided to take the plunge.

Novel-writing had intimated her because of its length, so she decided to think of every chapter as a short story. With this in mind, she churned out her first novel, Patternmaster, within months. She sent it to Doubleday, who published it in 1976, when Butler was taking a writing course by Theodore Sturgeon at UCLA. Her next four novels were published at a steady pace of a novel a year until she reached Wild Seed, published in 1980. The ones after that were published at longer and varying intervals. Butler’s early novels were all based on stories she had been thinking about since she was 12. They were in what she liked to call her “trunk,” and once she started publishing novels, they were written fairly quickly. It was when she was out of her old ideas that her writing slowed down and she had to think of something new, let it simmer, and then write it out.

Octavia Butler’s Literary Legacy

Up to her untimely death on February 24, 2006, from a fall outside her home, Butler published 12 novels and nine short stories. Her short story, “Speech Sounds,” won a Hugo Award in 1984. Bloodchild, a novella, won the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 1985 and 1984 respectively. In 1995, Butler won the MacArthur Fellowship, also known as the “genius grant,” an amount of $295,000 which was distributed over a period of five years.

Her first novel was part of the Patternist series, which starts with Wild Seed (1980) and runs through Mind of My Mind (1977), Clay’s Ark (1984), Survivor (1978), and Patternmaster (1976). The series begins in southern California, in the distant future, where people of the Pattern — humans with psychic abilities — hold power over ordinary humans, also termed “mutes.” There exists another species — the subhuman Clayark, who Butler expands on in Clay’s Ark. The Patternist series plays with power — who has it, who doesn’t, and who that affects. “One of the reasons I got into writing about power,” Butler tells Juan Williams in 2000, “was because I grew up feeling that I didn’t have any, and, therefore, it was fascinating.”

Her Xenogenesis series, later called Lilith’s Brood, includes Dawn (1987), Adulthood Rites (1988), and Imago (1989). The trilogy contends with what Butler terms the “human contradiction” — a conflict between intelligence and hierarchical tendencies. The first, we would like to believe, reigns supreme, but Butler argues that the latter are more deeply ingrained than we imagine. Yet Butler’s books in this series don’t lean towards social determinism. If anything, she explores a set of different possibilities that this conflict could lead to. This series also challenges notions of heteronormative sexuality and families.

The Parable series, also called the Earthseed series, consists of Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). Narrated in a series of journal entries, the series tells the story of Lauren Olamina, who lives in the gated community of Robledo, southern California in 2025. It begins with a frightening picture of the deprived life that Lauren lives. She is threatened by both people and the environment. The issue of global warming is so strong here that Butler called it a character in the story. Disheartened by the direction humanity has taken on earth, Lauren composes her own religion, Earthseed, with the ultimate goal of reaching the stars — literally. Written as a cautionary tale, Butler wanted to write a story that would explore the future of the human race, if we continued to go on as we are. The Parable series is that story.

Some have tried to fit Butler’s novels into a lens of black-and-white morality instead of the rich landscape of social commentary they contain. When asked if her books are about good and evil, Butler said, “I don’t write about good and evil with this enormous dichotomy. I write about people. I write about people doing the kinds of things that people do.”

Kindred (1979), Butler’s best-known work to date, was originally meant to be part of the Patternist series, but it was too much an outlier. It was marketed as soft science fiction, but Butler called it fantasy. Although the story features time travel, there isn’t a science to it in the book. Kindred tells the story of African American Dana, who is one day unceremoniously — and frighteningly — thrust back from 1970s California to the pre–Civil War south to rescue Rufus, the slaveholder who would one day father her ancestor.

When talking about her inspiration for the book, Butler describes arguing with a friend of hers who had studied Black history. She had admired his knowledge, but after this particular discussion, she realized that for all facts he knew, he hadn’t truly understood. He had said to her, “I wish I could kill all these old Black people who’ve been holding us back for so long, but I can’t because I’d have to start with my own parents.”

Butler realized that there were people out there who had similar views, who, like her as a child, did not understand the sacrifices her mother had made. “What I wanted to teach in writing Kindred,” she said, “was that the people who did what my mother did were not frightened or timid or cowards, they were heroes. I wanted to make that clear to people like my friend. I wanted to reach people emotionally in a way that history tends not to.”

First African American Woman Science Fiction Writer

In a genre written primarily by white men for white adolescents, Butler was an outlier, more so than now. One of the things she struggled with, as a Black science-fiction writer, was finding examples. While part of it was that Black authors are still a minority in science fiction, Butler also said that she just didn’t have enough exposure growing up. A lot of the books she read had all white characters with women who were treated as sexual objects. People of color rarely cropped up in her reading. Butler’s novels feature storylines with strong female characters, usually African American, with a diverse cast of supporting roles.

In an autobiographical essay published in 1995, Butler responds to the question, “What good is science fiction to Black people?” by writing:

What good is any form of literature to Black people? What good is science fiction’s thinking about the present, the future, and the past? What good is its tendency to warn or to consider alternative ways of thinking and doing? What good is its examination of the possible effects of science and technology, or social organization and political direction? At its best, science fiction stimulates imagination and creativity. It gets reader and writer off the beaten track, off the narrow, narrow footpath of what “everyone” is saying, doing, thinking — whoever “everyone” happens to be this year. And what good is all this to Black people?

OCTAVIA BUTLER, 1995

Writing Life

A lot of what Butler experienced during her lifetime went into her writing. All the menial jobs that Dana works in Kindred were things that Butler had done in her life. Most of her books are written about communities — people creating communities or dealing with changes within them — because she grew up in a community, and a sense of belonging was an important aspect of her upbringing. While teaching writing classes, she would tell her students that if something didn’t kill you, you would probably wind up using it in your writing.

Aside from life, Butler drew inspiration from anything that caught her attention. When she was between projects, she would go to a library, find a section she hadn’t been in, and simply browse. Sometimes she’d find something that interested her, other times she’d put a book away after a few pages. She called this process “grazing,” often taking home piles of books and audiotapes to read later.

“I love audio tapes,” Butler said to Charles Rowell in 1997, “I’m a bit dyslexic and I read very slowly. I’ve taken speed reading classes, but they don’t really help. I have to read slowly enough to hear what I’m reading with my mind’s ear. I find it delightful. I learn much, much more and better if I hear tapes. I can recall when I was a very little girl being read to by my mother. Even though she was doing the domestic work that I talked about, she would, during my very early years, read to me at night. And I loved it. It was, again, theater for the mind.”

In a similar vein, she would flip through her specialized dictionaries and encyclopedias when she went “shopping for ideas.” Sometimes something she read would make it into her books, like the image of a worm in her encyclopedia on invertebrates that she used to describe some of the aliens in her Xenogenesis series.

Butler liked to write in the early hours of the morning, when it was still dark out. This was true for the ten years that she worked temporary jobs, between 1968 to 1978. Although she purchased a computer in later years, she preferred writing on a typewriter. She loved writing when it rained. Later on in her career, she would come up with a routine: taking a walk between 5:30 and 6:30 a.m., doing work around the house, sitting down to write at 9 a.m., and cutting time out later in the day to read.

It was Butler’s mother who had bought her her first typewriter — a portable Remington. Although no one in her life had been encouraging of her writing career, her mother had been the most tolerant. Everyone else didn’t see writing as a practical occupation. Her mother’s dream for her was that she would one day get a job as a secretary and be able to sit down while she worked. Growing up, the expectation was not to aim too high. She could have been a secretary, teacher, or nurse. Recounting her options later in an interview with Jane Burkitt, Butler says, “They all sounded like levels of hell to me.”

Octavia Butler’s Personal Life

The myriad interviews I’ve read have shown that Butler not only had a sharp sense of humor but also had the ability to open up about her personal life. She often talks about her lonely childhood, about how she was the “out kid” that never fit in with her peers. In certain places, she mentions instances of being bullied by older kids. In elementary school, she would get “hit and kicked” by the older kids until she learned to fight back, though the latter was difficult for her because she didn’t like hurting people. She talks about how she was called ugly for most of her adolescent years, and how that affected her, “If you’re called ugly that long, you start to believe it. You also start to expect it so that, after a while, when people become too polite to do that you assume that they’re thinking it, and you start to miss it in a horrible sort of way.” In one particular instance, she mentions that adolescence was the only time she felt suicidal.

Butler recounts instances of being mistaken for men — on the phone, owing to her deep voice, and sometimes in person — and feeling offended during these occurrences. She said that her social awkwardness — she was painfully shy as a child — and her physical appearance led to her being removed, socially.

The upside is that it all pushed her to write: “Because of this, because I was so ostracized and because I was so shy,” Butler says in an interview in 1997, “the writing was a real refuge for me. So, in that sense, I guess you could say my body helped to make me a writer.”

In later years, Butler described herself as “comfortably asocial.” When asked to expand on this, her answer seems to echo the way most introverts feel today: “I like spending most of my time alone. I enjoy people best if I can be alone much of the time. I used to worry about it because my family worried about it. And I finally realized: This is the way I am. That’s that. We all have some weirdness, and this is mine.”

Before I started working on this essay, I had only read Butler’s Kindred. The novel had been advertised as her best science fiction, and it was the first novel by her that I read. Kindred was brilliant in how immersive it was — it was difficult, sometimes horror-inducing, but always, always compelling. I was struck by how Butler does away with any sense of nostalgia and wonder associated with time travel to plunge us straight into a terrible period in history. It was innovative and impactful.

Reading about Butler’s childhood, her career, and simply hearing her voice through the transcriptions of a number of interviews made me realize that there is so much more to Octavia E. Butler than what I first admired. Not only was she a brilliant writer and thinker, but she was also startlingly brave — both in how she was willing to be vulnerable during her interviews and in her persistence in following her dreams.

To end this piece on Butler, I am going to leave you with another interesting fact. In 2000, she did an interview with Charles Brown for Locus Magazine, called Persistence. Despite being a scholar who was deeply concerned about the direction humans were heading in — and rightfully so, if you’ve been paying attention to the news — and who often envisioned us in dark futures, Butler still said, “I feel hopeful about the human race.”

Sources:

- Conversations with Octavia Butler by Consuela Francis

- Octavia E. Butler by Gerry Canavan

- Science Fiction Writers: Critical Studies of the Major Authors from the Early Nineteenth Century to the Present Day by Richard Bleiler

- “Octavia Estelle Butler,” Voices from the Gaps (University of Minnesota—Twin Cities) by Jennifer Becker, edited by Lauren Curtright

Source : Who Was Octavia Butler?