“Gulliver’s Travels” shows us how modern science could benefit from a little satire

The first time I picked up Gulliver’s Travels, I was working in a protein production lab. I’d just gotten home after a painfully long day, half of which I’d spent on an experiment that mysteriously failed at the last minute — not a good thing when the deadline to get data is fast approaching — and I was more than a little stressed. Gulliver’s Travels happened to be the book nearest to the armchair into which I’d gratefully collapsed. But in spite of my mood (or perhaps because of it), Jonathan Swift’s imagination, his worlds in all their layered absurdity, fascinated me enough to read well into the night.

A similarly frustrating week would pass before I got to Book III of the Travels, where Gulliver travels to a city of people devoted to studying mathematics, but who can’t even build their houses level. A grand Academy, built for the brightest minds in the country, stands in the city center and is occupied by a motley of projectors (investigators, that is) who do things like try to determine the color of paint by touch and smell, or turn ice into gunpowder. Their attempts are met with approval by the city’s inhabitants, and only Gulliver feels there’s something ridiculous going on.

Maybe it was my irritation with the work I was doing, but in reading Swift’s satire on the science of his day, I could see the spitting image of modern scientific practice.

Admittedly, my response wasn’t typical. Almost 300 years separate our world from the one Swift lived in, and for most people, the Academy of Projectors Gulliver visits seems at first glance a crude caricature of today’s multi-billion-dollar research institutes and university science departments. The instinctual reaction is to scoff — surely modern science doesn’t involve some crackpot squirreled away in a lab waving fistfuls of test tubes, right? After all, advances in science since the 18th century have been responsible for everything from the eradication of smallpox to the launch of the International Space Station.

But first impressions aren’t always perfect. It’s worth pushing through that initial reaction and thinking through the similarities between the discipline of science that Swift saw and criticized, and the science of today. The two have more in common than first meets the eye. Even now, three centuries on, reading Gulliver’s Travels can give us insights into modern science and its relationship with the world.

We just need to know what to look for.

Even now, three centuries on, reading Gulliver’s Travels can give us insights into modern science and its relationship with the world.

I’ll start by saying something about what makes Gulliver’s Travels effective at delivering its criticisms. Throughout the novel, the protagonist, Lemuel Gulliver, repeatedly encounters worlds which seem completely alien to the one he knows. On Lilliput, he meets a race of people one-twelfth the size of regular humans, living in tiny villages and cities. In Book IV, he comes face-to-face with a breed of talking horses and their vaguely humanoid slaves.

Swift hides his satire behind a veil of fantasy, and it’s only when we look closely that we see the mirror he holds up to society.

The Lilliputians may be tiny, but their capriciousness and cruelty easily match the extremes of which humans are capable. The talking horses might appear to be objects of slapstick humor, but they spend their days actively plotting genocide.

Time and time again, the worlds Gulliver visits and the beings he meets come to embody the worst of human nature and society, and Swift is so effective at leveling his criticisms because he withholds recognition of that humanity for as long as possible.

Swift hides his satire behind a veil of fantasy, and it’s only when we look closely that we see the mirror he holds up to society.

By presenting the familiar wrapped up in the exotic, Swift makes us, as readers, first experience, then intuit, and only then recognize and think.

It’s no surprise, then, that Gulliver’s Travels is often seen as one of the first science fiction texts in the English canon. After all, Swift is using a technique that in the years after him science fiction has come to perfect: burying the narrative’s relevance in a world so completely unknown that we can’t rely on our previous experience to recognize it. Darko Suvin, one of the best-known sci-fi literary theorists, describes it like this:

SF is… the space of a potent estrangement… [it is] a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.

“The presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition.” In other words, Swift goes out of his way to make the worlds he builds strange and unfamiliar, which causes us to bypass the fog of experience and see them afresh. And then cognition kicks in — then, once we’ve judged them properly, we can realize how similar they are to what we know, and hopefully come to a much more sober reflection on our own society.

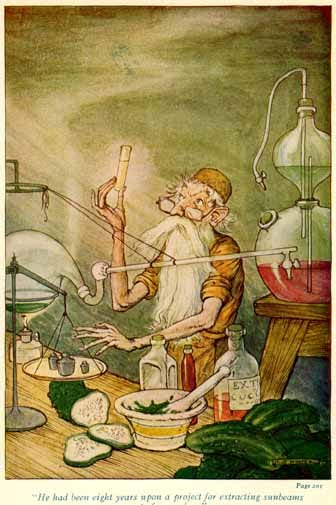

All this brings us neatly back to Gulliver and the Academy of Projectors. By now it should be clear that here, like everywhere else, Swift gives us situations that we’ll first judge as ridiculous, and only then start to recognize. So Gulliver’s first encounter is with a scientist in the Academy who

had been eight years upon a project for extracting sun-beams out of cucumbers, which were to be put into vials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the air in raw inclement summers. He told me, he did not doubt in eight years more, he should be able to supply the Governors Gardens with sunshine at a reasonable rate…

Mostly, this is funny because it’s incongruous — because the certainty with which the projector speaks doesn’t match up with the absurdity of what he’s suggesting. But for the more astute of Swift’s 18th-century readers, there would be a spark of recognition following the smirk.

By the time Gulliver’s Travels was published in 1726, the Royal Society of London, established 126 years earlier to bring about “the improvement of Natural Knowledge,” was starting to be viewed with a bit of skepticism. Partly, this was because its achievements at the time weren’t quite as numerous as people had hoped, but it’s also clear that Swift, like many others, saw some of the society’s activities as rather ludicrous.

In a 1937 essay, critics Nicholson and Mohler showed that the majority of the projects in Swift’s Academy aren’t really that far removed from what the Royal Society was working on at the time. The “sun-beams from cucumbers” idea, for instance, probably came from actual attempts at using plants to convert sunlight into gas, and experiments in bottling and selling regional air.

But that was then. How relevant is Swift’s idea about the absurdities of 18th-century science to the science of today?

Well, in one sense, the discipline has changed a lot since 1726 and has many more accomplishments to speak of. Science has certainly benefited from the process of institutionalization, and the persistent efforts of scientific organizations and the scientists in them have led to humans living longer and healthier lives. They’ve allowed us to manipulate the world in unbelievable ways, to build skyscrapers and airplanes. Science has cured diseases and saved lives, explored everything from the microscopic cell to the frontiers of space.

10 Satirical Covers for the Terrible Books You Can’t Get Away From

It’s important to remember that many of these advancements would never have come about if scientists weren’t willing to entertain the seemingly absurd — after all, the methodology of science has always been to take small steps in the direction of making the absurd a reality. As sci-fi writer Arthur Clarke put it, “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.”

But at the same time, the inexorable, institutional pursuit of science has some troubling consequences. As our scientific knowledge has grown over the years, it has become increasingly segmented and stratified. To take one example, my field of study, genetics, was all but unknown until a century ago. In the seven or so decades since the structure of DNA was discovered, the field has split into literally dozens of sub-specialties. Many of these, like evolutionary genomics and pharmacogenetics, are as alien to each other as completely different branches of science.

The inexorable, institutional pursuit of science has some troubling consequences.

We have to pause and consider what impact this segmentation of knowledge may have. Swift’s projectors in the Academy are ridiculous (and pitiful) partly because they’re so engrossed in their research that they have no ability to look up, step back and see the bigger picture. And as humanity’s wealth of scientific knowledge grows, it’s getting more and more difficult for researchers and students alike to maintain a sense of perspective. Already in many universities, science programs allow little to no scope for exploring other disciplines like the humanities.

It’s increasingly the case that in science, one has to learn more and more to become an expert in less and less. This trend cannot be good for our development as individuals, and it should worry us a great deal more than it seems to.

One of the reasons we don’t often think about such things is that our society, generally speaking, doesn’t like criticizing science. I don’t mean in the sense of climate change deniers or the rabid anti-vaccination movement — we’ve got plenty of those, unfortunately. I mean that serious methodological debate about science as a whole isn’t something we’re comfortable with.

This, too, was a problem that Swift identified early on. During his tour of the Academy, Gulliver meets a projector whose task is “an operation to reduce human excrement to its original food,” and that wonderful interaction starts off in a striking way:

I went into another chamber, but was ready to hasten back, being almost overcome with a horrible stink. My conductor pressed me forward, conjuring me in a whisper to give no offence, which would be highly resented; and therefore I durst not so much as stop my nose.

This is one of the most revolting scenes in the entire novel, and Swift uses that repulsiveness to demonstrate the cult-like reverence the Academy has generated for itself. Such is the power of the institution that the danger of offending its practitioners supersedes all other concerns — even ones of basic hygiene.

There’s a serious point here: in observing the institutionalization of science in the 18th century, Swift saw the very real danger of it becoming an increasingly inaccessible, incontestable, and monolithic discipline. And unfortunately, it looks like his fears were justified.

In observing the institutionalization of science in the 18th century, Swift saw the very real danger of it becoming an increasingly inaccessible, incontestable, and monolithic discipline.

Just last year, I met a student at the University of Edinburgh who told me that philosophers have no place commenting on the dealings of science. That only scientists have the right to judge science. Sadly, this is a common view, coupled with a growing belief that science is the only useful way of interpreting the world and gaining knowledge about it.

“What are you studying that for?” is a reaction I get regularly when I tell people that I study English literature as well as genetics. Sometimes it’s subtext. Sometimes it’s not.

Because of the very visible scientific achievements that have made our lives so much better over the years, people are forgetting that there are some questions about our existence science in principle can’t answer. Important questions, like “How should one act in order to be a good person?” and “What can we do to understand the experiences of others?” Questions that we cannot afford to lose sight of.

But the scientific mindset is at risk of overshadowing the forms of inquiry that are best suited to probing these questions, and that worries me greatly. When funding is cut to university departments, it is invariably historians, literature scholars, sociologists, artists, and anthropologists that suffer first, rather than physicists, mathematicians or computer scientists. Once upon a time, philosophers were the most esteemed members of society. Now, largely because of a lack of job funding, the vast majority of philosophy majors will never work in their chosen discipline.

And it’s a shame, because science is at its most beautiful and extraordinary when it shares the stage with other disciplines. When the insights it generates supplement other modes of thinking. When it steps into dialogue with philosophy, law, medicine, history.

The scientific mindset is at risk of overshadowing the forms of inquiry that are best suited to probing these questions.

Incidentally, the prestige of scientific authority that Swift saw as an emerging problem isn’t just something that affects the status of other fields. It’s also a reality that scientists themselves have to deal with.

Before he published a single word on evolution by natural selection — what would become the most successful scientific theory in biology — Charles Darwin spent 20 years gathering data, repeating his studies and thinking through his ideas. “You know what would happen to me if I did that?” an evolutionary biology professor from my university once told me. “I’d lose my job within a year.”

The drive to actively contribute to the prestige science commands — to further the cause of science — has led to a “publish or perish” culture in the field. Researchers are spending less time than ever reflecting critically on their work and much more time writing grant applications and publishing papers. Increasingly, quantity trumps quality.

Add to this the fact that many scientific journals are reluctant to accept negative results, and it’s no surprise that science is in the midst of an unprecedented reproducibility crisis. A 2016 article published by Nature found that of more than 1,500 researchers surveyed, over 70% had tried and failed to replicate the results of another study. In cancer biology, a 2012 inquiry estimated that as few as 11% of published results are actually reproducible. This is a major problem whose scale we’re only now starting to realize.

And broadly, this was exactly Swift’s point. If we consider the methodologies of science as a discipline to be beyond criticism, if we invest in it to the detriment of other human attempts at understanding the world — if we never step back and see the broader picture — there will be very real and devastating consequences.

If we invest in science to the detriment of other human attempts at understanding the world, there will be very real and devastating consequences.

Gulliver’s trip to the “practical” side of the Academy ends with a visit to the resident doctor, who first outlines his ingenious idea for treating colic — pumping and then sucking air through the rectum with a pair of bellows — and then demonstrates it: “I saw him try both experiments upon a dog… the animal was ready to burst, and made so violent a discharge… the dog died on the spot, and we left the doctor endeavoring to recover him by the same operation.”

The shock value is strong here, but the graphic imagery also reveals an unrecognizably, unfathomably barbaric side to science. And as always, there’s a deliberate delay for us to respond emotionally before we start to think about how accurate this depiction is — whether the science we know and trust really has the capacity for such harm, literally or otherwise. The answer isn’t easy to come to terms with.

So Swift’s final image of the dog and the doctor becomes a sad metaphor for a terrifying possible future — for a discipline scrambling in vain to repair the untold damage done in the wake of its unchecked and unquestioned progression.

In spite of all this, it’s important to remember that Gulliver’s Travels wasn’t an anti-science book. Jonathan Swift didn’t have a beef with the idea of science in principle — after all, he was writing during the Age of Reason, the Enlightenment. The very fabric of his satire, as we’ve seen, only works if people think.

Swift’s problem was with the way science was being practiced, and especially with the people who would preach it to the exclusion of everything else. By relying on rationality in his criticisms, Swift actually showed his support for the underlying principle of good scientific practice: careful and considered reason. It’s just that science shouldn’t be allowed to eclipse other modes of thought.

Three centuries on, we would do well to heed his warnings.

What Science Can Learn from Constipated Dogs was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.