Yu Hua and his translator discuss “The April 3rd Incident,” which revisits the writer’s early work

I n 1984, a Chinese dentist named Yu Hua decided he was sick of looking at teeth all day. He wanted more variety, and more freedom. Maybe he wanted to become a writer. By 1994, he was among the most celebrated novelists in China.

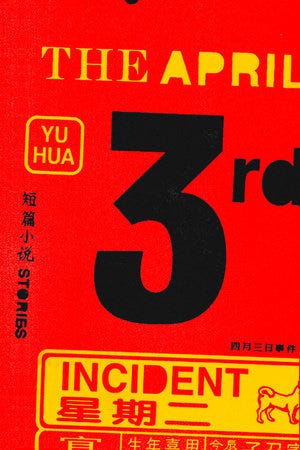

Yu Hua’s early work sprang from his desire for freedom and exploration, and from reading modern and postmodern writers like Borges, Faulkner, and Kafka. The characters in his early stories, seven of which are collected in his most recently released book The April 3rd Incident, are trapped in their own subjectivity, the world around them a baffling fog. The teenage protagonist of the title story, who convinces himself his family and friends are plotting against him, bears more than a passing relationship to Juan Dahlmann, the delusional librarian in Borges’ masterwork “The South.” In another, “In Memory of Miss Willow Yang,” Yu Hua numbers and then rearranges the story’s sections, presenting the narrative outside chronological order. And in “Summer Typhoon,” the collection’s longest and most lyrical story, he describes a weeks-long earthquake panic through the eyes of an entire community.

In more recent years, Yu Hua has turned from metafiction to character-driven fiction and political criticism. He’s an op-ed contributor to the New York Times and the first Chinese winner of the James Joyce Award, and his work has been translated into 35 languages, from Catalan to Tamil. In the United States, he’s perhaps best known for his novels Brothers and To Live, or his essay collection China in Ten Words. Anyone who has read those books is in for both a surprise and a treat with The April 3rd Incident, and anyone new to Yu Hua’s work could find no better place to start.

I interviewed Yu Hua via email about the experience of returning to stories from decades ago. His translator, Allan H. Barr, translated my questions and Yu Hua’s replies; he and I then corresponded about his experience translating The April 3rd Incident. Both interviews are below.

Yu Hua

Lily Meyer: How did it feel to revisit these stories decades after writing them? Were you able to approach them as a reader, or only as a writer? Were you tempted to make changes?

Yu Hua: Revisiting these stories now, what strikes me most forcibly is that I no longer have the talent I had when I was young — though, of course, when I was young I didn’t have the talent I have now: they’re different kinds of talent. Changes in my society have made me into an author not so very much like the one I used to be: these days my writing is much more direct in addressing social realities. When I reread these stories, I sometimes feel an impulse to change the odd line here or there, but I haven’t done that, because those were lines that the younger me wrote, not the current me. That being so, I don’t feel I have the right to make revisions.

LM: Your writing since The April 3rd Incident has become much more character-driven, where these stories tend toward the conceptual. Are you still attracted to this abstract mode of writing? What can you achieve through the abstract that’s harder, or not possible, through the concrete?

YH: These stories were written before I began to write full-length novels, and you’re right, they’re a little abstract — certainly in terms of the characters, which to a large extent are symbols, symbols that emerged when I was trying to give expression to things. Once I started writing novels, I suddenly discovered that characters would often speak in their own voices, in words that were better — more apt and more natural — than the ones I originally had in mind, and so later my writing, as you say, became much more character-driven.

Revisiting these stories now, what strikes me most forcibly is that I no longer have the talent I had when I was young — though, of course, when I was young I didn’t have the talent I have now.

LM: You’ve spoken often about your influences over the years, and Borges seems to me to be a particularly clear influence in The April 3rd Incident. What did you take from his style, and how did you transform it so completely into your own?

YH: Borges had an impact on me, certainly, and you can see that in this book. Some of the stories, however, were written before I came into contact with Borges’ work. I wrote the title story, for example, in 1987, before ever reading Borges. At that point I was under Kafka’s spell. The sensation I got from reading Kafka was a compulsive feeling of dread, a dread that I felt as my own. And so what I received from Kafka was not an influence in terms of form or technique, but rather an emotional influence. Kafka activated a sense of dread that had been lurking deep in my heart, and then I gave it expression in my own way.

LM: “The April 3rd Incident” is one of the funniest and saddest articulations of adolescence I’ve ever read — its protagonist felt very much like Holden Caulfield — and yet it skates constantly on the edge of true darkness. How did you keep it on that edge?

YH: Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye was all the rage in China in the late 1980s and still is popular today, I think because you can find lots of Holden Caulfields, in any country and any era. The “he” in “The April 3rd Incident” is very different from Holden, but in one respect they are alike — both are excluded from the crowd, or they exclude themselves, because they don’t want to be part of it. That description of yours — “Skating constantly on the edge of true darkness” — is spot on, for that was precisely my state of mind as a 27-year-old writing this story. And it’s true that I needed to get the balance right; my method was to not let the protagonist ever get too excited, for that would fatally disturb the story’s equilibrium.

Kafka activated a sense of dread that had been lurking deep in my heart, and then I gave it expression in my own way.

LM: In “Summer Typhoon,” you write in the voice of a community, though never in the first or third person plural. How did you get the balance of characters and voices right?

YH: It would have been impossible to tell this entire story from the viewpoint of a single character — it needed multiple perspectives, but each character is independent, with a distinct voice that is his or hers alone. It’s not that easy to write a story from multiple angles: first you need to think about an order in which to introduce the various viewpoints, and then work out the transitions from one to the next. As for balance, I felt that the never-ending rain and the characters’ shared fear of an earthquake could help me there, for these things create an atmosphere that envelops both them and the reader. Just so long as I didn’t disrupt that atmosphere, the narrative could remain secure and keep its balance.

LM: In “In Miss Willow Yang,” the characters often find their knowledge of the world coming into direct conflict with their experience — take, for example, the narrator walking into his kitchen, which he knows doesn’t exist. What attracted, or attracts, you to that particular paradox? Does it have political echoes?

YH: By the time I wrote “Miss Willow Yang,” almost two years had passed since I wrote “The April 3rd Incident,” and by then I was a reader of Borges; I’m sure that Borges must have left his mark on this story. It is a slippery or, as you say, paradoxical narrative: as it progresses, it constantly contradicts itself. Its paradoxes probably do have political implications, for when I wrote the story I had still not fully emerged from the shadows of the Cultural Revolution. The Communist faith that had been inculcated in me from childhood to adolescence had all at once been discredited, and things that later I’d begun to believe in I very soon stopped believing in, so I was myself living in a paradox. That, too, was the political reality in China in those days: Deng Xiaoping wanted to repudiate the Cultural Revolution, but he refused to repudiate Mao Zedong, and that was the biggest paradox of all.

Trading the American Dream for the Promise of a New China

LM: When the outlander in “Miss Willow Yang” starts losing his sight, you write, “From that day on, he no longer took responsibility for his own body.” That seems true for a lot of the characters in The April 3rd Incident. Did you feel that way at the time? What’s the source of these character’s lack or loss of control?

YH: That loss of control seems to have been a keynote of the stories I wrote 30 years ago: the characters have no command of their own destiny, and sometimes they even lack a command of their own sensations. I’m not sure what caused me to create such situations, but one thing I can say with certainty: I encouraged myself to keep on writing such stories, because this sense of a loss of agency was something that I myself often felt, and I needed to get it off my chest. It was when I had unburdened myself of this feeling that I began to write novels, and then my writing moved in a new direction.

Allan H. Barr

LM: How did you come to work with Yu Hua, and in what ways did you collaborate or use him as a resource?

AHB: In my early academic career, I focused largely on the literature of late imperial China, but I always had an interest in current developments, and in time I thought I’d try my hand at translating a living author. It’s not that common for scholars of pre-modern China to get involved in contemporary literature, and when Yu Hua and I met for the first time in Beijing in 2001, he was rather tickled that someone with a background in Ming and Qing fiction would want to translate his work. We soon found we enjoyed working together, and by now I have now translated five of his books — two novels, two short-story collections, and a volume of essays.

In this case, Yu Hua personally selected seven stories that he thought would make a representative collection of his early work, and I suggested an order in which to arrange them. We also conferred about the title. As I was translating the stories, I emailed Yu Hua regularly with questions about particular words or passages that I wasn’t sure I fully understood. In some cases, I was relieved to find, the problem was not with my reading comprehension but with the text itself: the 1995 edition of Yu Hua’s collected works on which I basing my translation turned out to include a number of typos that his Chinese copy editors had failed to detect.

In some cases, I was relieved to find, the problem was not with my reading comprehension but with the text itself: the 1995 edition on which I basing my translation turned out to include a number of typos.

LM: The stories in The April 3rd Incident are simultaneously vague and detail-driven, and their humor, especially, lives in detail. Were there details you had to change to make the English version work?

Allan H. Barr: It’s true that a combination of vagueness and detail is a hallmark of Yu Hua’s narrative style. Precisely because details are relatively sparse, I am always keen to know just how Yu Hua visualizes the things that do make an appearance in his work. For example, in a couple of his novels we encounter the simple word yáng羊. Potentially this could mean “sheep,” or maybe “lamb,” or possibly “goat.” Which is it? Sometimes you can’t be sure about this kind of thing unless you ask Yu Hua himself. In “Love Story,” Yu mentions an item of clothing that translates literally as a “student dress.” What exactly is a “student dress”? His answer, when I asked him, was that at the time this story is set a student dress was a prized item in a young woman’s wardrobe; made with Dacron, it was deemed more fashionable than dresses made with cotton fiber. So I adjusted my translation accordingly and called it a “Dacron dress.”

LM: With stories like “Miss Willow Yang” and “The April 3rd Incident,” the reader has to be confused and uncertain for the story to work. How did you make sure not to give too much away as you translated?

AHB: You’re quite right that confusion and uncertainty are critical to the success of these two stories. A good deal of the confusion is actually hard-wired into their design, and there’s little I could have done to alter it. “The April 3rd Incident,” for example, is divided into 22 sections, numbered sequentially from 1 to 22, but the sections are not presented in the chronological order of the events that take place. Rather, they are arranged according to another scheme of Yu Hua’s devising, so that section 9, say, follows section 7 in terms of conventional narrative time. “Miss Willow Yang” is also divided into numbered sections, 13 in all, but in four sequences (numbered 1, 2, 3, 4; 1, 2, 3, 4; 1, 2, 3; and 1, 2), each sequence relating much the same story, but with significant — and perplexing — variations. So any translation that follows the original plan of these two stories is bound to throw the reader off balance to some degree.

One concern I had when translating “The April 3rd Incident” and “Summer Typhoon” was that they might actually sow a little too much confusion. In the original Chinese text of these two stories, the internal musings of characters are not visibly demarcated from the actual events, and Yu Hua and I agreed it would make sense to put internal imaginings in italics, Faulkner-style, to help the reader navigate what might otherwise be a rather too bewildering landscape. But plenty of confusion and uncertainty remains.

How a Japanese Novella about a Convenience Store Worker Became an International Bestseller

LM: Which story in this collection was the hardest to translate? Which was the most fun?

AHB: The hardest would have to be “Summer Typhoon.” Of the pieces in this book, its narrative arc is the least clear; it evokes an atmosphere more than it tells a story. Reading it, more than once I was unsure just what was happening, and several times I sought advice from Yu Hua as I considered how to present a scene or wondered whether to clarify something or leave it a bit mysterious. The most fun was definitely “The April 3rd Incident,” with its offbeat humor and its exasperating but oddly endearing hero.

LM: There are some moments of amazing lyricism in these stories — I’m thinking particularly of “Summer Typhoon.” How do you match your own lyrical language to Yu Hua’s?

AHB: The lyrical passages certainly stand out in “Summer Typhoon,” contrasting starkly with the scenes of discomfort and anxiety that form so much of the story. I suspect that these lyrical passages recall scenes that Yu Hua himself may have observed on his travels in China, but they describe places that are unfamiliar to me, and so I had only his words to go on as I thought about how to render these passages in English. Fortunately, having known Yu Hua a long time, I think I have a sense of what words will be a good match for his.

LM: How much do you want readers to think about your presence as a translator, or the fact that these stories are translated?

AHB: I take it as given that most readers are not going to think about the fact that the stories are translated, and I don’t have a problem with that. But I certainly appreciate it when — as here in this interview — a reader takes the trouble to think about the work involved in translating into English such a different language as Chinese.

What It Takes to Write, and Translate, Some of China’s Most Famous Stories was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : What It Takes to Write, and Translate, Some of China’s Most Famous Stories