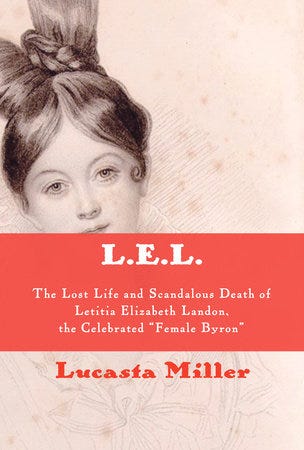

Lucasta Miller on the complex cultural and gendered reasons why women writers disappear

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” by Lucasta Miller is a sirenic, ultramodern biography. Miller’s sleuth-scholar storytelling engages an inventive tone to unravel hidden, seismic-secrets of the nineteenth-century London literary landscape. The finessed feat accomplished by Miller is a restoration of Letitia Elizabeth Landon’s prolific oeuvre.

Confession: Fearful of immersing myself into a stodgy classic read written by a London literary critic, I considered passing on this interview. Drained by the holidays and having just published a personal essay, my mind was processing thoughts on the literary marketplace and its thorniness towards trauma’s complexity and content currency. Miller’s response as to why L.E.L.’s story remains relevant changed my mind:

The commodification of the private self is endemic in our Instagram culture, having been democratized at a cost. The idea that you have to market yourself to survive is something Letitia Landon — who thought “society is a marketplace” — would have recognized. What makes her special is the way in which her work surreptitiously registers the conflicts and traumas that entailed, especially for a woman.

L.E.L. broke ground for ambitious women writers. Her mastery of linguistic and narrative ambiguity popularized her work and opened it up to interpretation while also turning her into a transatlantic celebrity. Landon wrote in many genres: poetry, novels, reviews, annuals and, had she lived in the 21st century, would have gathered to gab with Lady Gaga, George Saunders and Saeed Jones.

The author and I attempted to talk over the phone but our bad connection prompted Miller to remark in a pristine British accent, “You sound as if you’re talking through a wet towel.” We spoke over email about slut shaming, the risk of female ambition, and the parallels between Taylor Swift and Letitia Elizabeth Landon.

Yvonne Conza: Is there a particular conversation that you hope emerges from your book?

Lucasta Miller: I hope that the book will contribute to the conversation about the complex cultural and gendered reasons why women writers have so often disappeared and failed to make it into the canon.

I desire readers to come away with a clearer picture of the “strange pause” between the Romantics and the Victorians, that odd, underexplored gap in the history of English literature that L.E.L. inhabits. In her story you can see before your eyes how the world of Regency rakes and Romantic rebels transitioned into that of Victorian values.

I would also love for readers to see L.E.L. as a contemporary figure in some respects: the woman who wrote “I lived only in others’ breath” and would have understood the social media era. Her story resonates with the #MeToo generation, not just in terms of the sexual politics of workplace affairs or the so-called “casting couch”, but in terms of the slut-shaming to which she was subjected by male peers in the industry. L.E.L.’s story speaks to the ambiguities as much as to the clarities of that debate as she was not a simple victim but a woman trying to pursue her ambition who found that the system she tried to game was more powerful than she was. Above all, I want readers to come away understanding that L.E.L. is an irreducibly ambiguous and slippery figure and to be OK with that.

I hope that the book will contribute to the conversation about the complex cultural and gendered reasons why women writers have so often disappeared and failed to make it into the canon.

YC: Did it concern you that L.E.L. might be seen only as a victim or as ambitious seductress?

LM: Actually, when I first started working on L.E.L., #MeToo had not yet taken off, but I was always aware that her story was going to foreground issues to do with gender, not just in terms of social and economic equality but in terms of the cultural construction of “femininity”. I was always concerned to keep in play her complexity and not to reduce her to a single paradigm, though she herself brilliantly manipulated all her culture’s clichés of femininity, from tragic victim to sassy seductress.

YC: What does your book tell us about the double standards between men and women writers?

LM: There are so many issues here: what women/men write, what women/men read, how gender is treated in the media. Is ambition the desire for success or the fear of failure? When the latter becomes too dominant it can be self-defeating.

There’s certainly less of a double standard in many respects, especially sexually. Gone are the days when a man can sire as many illegitimate offspring as he likes but single mothers are pariahs. (Contextual note: William Jerdan, editor of the Literary Gazette was not only L.E.L.’s mentor, publisher and promoter, but he sired three illegitimate children with her, leaving her vulnerable to press exposure and scandal.)

But as for the literary industry, when I was working as deputy literary editor at a British national newspaper in the 1990s, I used to have to make a conscious effort to make sure we had at least one or two women reviewers on our pages every week (my boss, the literary editor, was a man). In terms of the literary marketplace, it would be interesting to do some research into whether there’s a gender pay gap today — not at the apex in what has increasingly become a winner takes all marketplace (I’m not talking about J.K. Rowling) but at the ordinary level of people making their livings in journalism and publishing both online and in print.

YC: Taylor Swift’s genius as an artist and a savvy marketer shares a platform that reminded me of L.E.L. — in today’s world and back then, talent is not enough. In her desire to achieve success, is an ambitious woman more likely to risk her reputation?

LM: Yes, you can see the parallels quite easily. However, the difference with L.E.L. is that the split between what we now call “high” and “popular” culture had not yet happened so she regarded Keats, Shelley and Byron, who are today enshrined as canonical greats, as her male avatars — with all the complexities that brought for her as a woman, given that the male Romantics, though politically liberal, were far from feminist.

For L.E.L., ambition was a minefield. The constant vein of self-destruction found in her work, symbolized by Sappho’s story, reflects the paradox of her situation: to assert herself in public was to risk her own destruction.

L.E.L.’s subjective experience at the hands of the printed and oral gossip of her day was probably not dissimilar. Because of the nature of culture then and now, a woman’s desire to be noticed and succeeded remains more problematic than it is for men.

YC: How do you explain L.E.L.’s ability to understand, and succeed in, the literary market place of the 19th century?

LM: She was educated in the Regency culture of feminine accomplishments which emphasized people-pleasing, though at the same time she was also a childhood rebel who identified with lone wolf male protagonists such as Robinson Crusoe. In the competitive literary market of the 1820s, in which marketing and audience manipulation were at a premium, feminine wiles arguably worked better than simple male assertions of authority.

L.E.L’s story resonates with the #MeToo generation, not just in terms of the sexual politics of workplace affairs or the so-called “casting couch”, but in terms of the slut-shaming to which she was subjected by male peers in the industry

YC: Is there a writer today that you see as comparable to Letitia Elizabeth Landon? Anne Sexton?

LM: Your comparison with Anne Sexton is interesting. I think ambiguity has often been the space available to women writers who have felt their voices compromised in a male-dominated culture. L.E.L.’s confessionalism is rather different because she is always playing a public role and often speaking through a fictionalized double. When one thinks of L.E.L. one mustn’t just think of her as a poet but as a sort of performer. For her the role of poetess was not dissimilar to that of the actress or diva. Perhaps we should look to modern examples of performers rather than poets to find a comparison. The famous singer dying of a drug overdose — Judy Garland for example — is a feature of modern celebrity culture.

YC: Who are the writers that benefited most from the groundwork laid down by L.E.L. with respect to first person female voice?

LM: Elizabeth Barrett Browning was always fascinated by L.E.L. Her Aurora Leigh (1856) is a narrative poem — a sort of novel in verse — written in the first person voice of a fictionalized female writer. As such it picks up on L.E.L.’s works, for example Erinna, but it also tangentially references aspects of L.E.L.’s life, such as the attic “room of one’s own” and the demands of writing for the market. However, it completely desexualizes the heroine and saves her from the need to write commercially by marrying her off at the end.

On the whole, the female first person voice was not the chosen mode for the best Victorian women writers who came after L.E.L., from Elizabeth Gaskell and George Eliot to Mary Braddon. When Charlotte Brontë used it in Jane Eyre (1847), in combination with a passionate love story, her morals were called into question.

Why Was Norah Lange Forgotten?

YC: Did you need to become completely obsessed with L.E.L. to understand her? And, did that ever become an obstacle as you were developing the book? Or, was it the fuel that drove the story?

LM: During the project, I often felt trapped in a hall of mirrors or entangled in a web. The fact that her first biographer slit his throat in 1845 was not a very consoling thought! I was determined to keep going because I wanted to make sense of the so-called “ mystery of L.E.L.” in a way that would satisfy me. So much was covered up after she died — especially to do with her affair with William Jerdan and her secret illegitimate children. The problems, from a research viewpoint, were manifold, including the sheer volume of material. Reading the sources, it often turned out that the absences spoke more loudly than the words. There was almost no line in L.E.L.’s work or her contemporaries’ accounts, which could be fully made sense of “straight” i.e. in a vacuum. Everything required contextualization, because she was so completely of her moment and so embraced being “modern” in Baudelaire’s sense of “the transitory, the fleeting, the contingent”.

All the sources had to be collated and cross-referenced. But even once the basic facts have been established, L.E.L. will always remain slippery. She is so labile that you have to let go of the traditional biographer’s unspoken assumption that the subject has a fixed and consistent core to their personality. Having worked on The Brontë Myth, which charts the sisters’ biographical image through time, I was geared up to take a questioning attitude to the art of biography, and to listen to Virginia Woolf who said “a biography is considered complete if it merely accounts for six or seven selves, when a person may have as many thousand”. When that person — L.E.L. — staked her career on role-play and masquerade you have to question all the more searchingly.

YC: Is there anything comparable today to the Literary Gazette where L.E.L. first published and became a major contributor via her reviews and work as an editor?

LM: The magazine market was different in the 1820s, so there isn’t a direct comparison, partly because the market was not yet segmented into “high” and “popular”/ “commercial” culture in the same way as today. However, in some respects, the boom in print culture of L.E.L.’s era, fueled by technological advances in printing and by a growing consumer base of literate people with disposable income but little experience of being literary consumers, prompted some of the same worries as are now hitting the Facebook generation. In the “puffery” era of the 1820s, publishing was in some respects a cowboy culture, and readers were implicitly regarded by some in the industry as a gullible source of revenue. Today, the issue is data-harvesting for sophisticated “invisible” target marketing. But the notion of the reader/consumer manipulation is nothing new.

L.E.L brilliantly manipulated all her culture’s clichés of femininity, from tragic victim to sassy seductress.

YC: What went into your decision to go to Cape Coast Castle in Ghana where she died? As you mentioned to me: “I couldn’t let L.E.L. go without seeing the place where she died.

LM: I think I went there to find some feeling of closure. I’d been entangled in L.E.L.’s web for so long. The extraordinary thing about her is that her story touches on so many wider historical currents such as the history of the slave trade and colonialism. At every level she’s like a person without boundaries, open to every current, a live wire through whom all the complexities of her era flow.

YC: In the book you wrote about visiting Cape Coast Castle: “Only when the guide takes us into the slave dungeons below ground level is its traumatic history made visible.” Then you continue:

In none of her letters home does Letitia mention the dungeons or the castle’s history as a slave fort. The perpetual swoosh of the ocean waves — pleasant enough for the hour or two I spend there, but inescapable — seems to echo the constant low-level interference of the suppressed. Letitia lived her entire adult life with the stress of the unspoken: “none among us dares to say/What none will choose to hear.

Would you clarify the meaning or symbolism of: “none among us dares to say/What none will choose to hear.”

LM: L.E.L. made damn sure her readers could never fully clarify her meaning! That’s how she tried to hook them and kept them reading. There’s something almost postmodern about her writing in her refusal to ‘own’ her own authorial intention, though it also reflects her lack of agency within the literary marketplace and as a woman and a mistress. She’s a skeptic and a relativist (“No one sees things exactly as they are, but as varied and modified by their own method of viewing”) but there’s also a deep vein of nihilism in her work which, I believe, is related to her life experiences and the culture she inhabited.

That said, these particular lines clearly refer to the human need for denial and, more specifically, to the endemic hypocrisy of the society in which she lived. Their private significance could only have been guessed at by the cognoscenti at the time who were apprised of the rumors about her private life. The biographical point to make is that the lines were written in the year she gave birth to her third and last baby Laura, who, like the other two, was given up and could not be openly acknowledged. As a “fallen woman”, she was to some extent “hiding in plain sight”, which is what this quotation is about. The same could be said of the shady businessman Matthew Forster, who introduced her to her husband, in his contraventions of the slave trade laws.

YC: Are there any projects that you are working on now?

LM: At the moment I’m teaching creative writing to women refugees. I’m also doing a short book on Keats and have plans to put together the libretto for a song cycle based on Wuthering Heights for my singer husband to perform. (It suddenly occurs to me that being married to a performer might have unconsciously helped me in my efforts to understand L.E.L…)

YC: Labels attached to you have included: “literary critic,” “biographical deconstructionist,” and “scholar” — what descriptive words would you assign to yourself for this book?

LM: I would love to think I could be all those things and at the same time be a storyteller.

About the Author

Lucasta Miller is a British literary critic who has worked for The Independent and The Guardian, and contributed to The Economist, The Times (London), The New Statesman, and the BBC. She was the founding editorial director of Notting Hill Editions and has been a visiting scholar at Wolfson College, Oxford, and a visiting fellow at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. She lives in London with her husband, the tenor Ian Bostridge, and their two children.

About the Interviewer

Yvonne Conza’s writing has appeared in Longreads, Catapult, Cosmonauts Avenue, The Rumpus, Joyland Magazine, Blue Mesa Review, F(r)iction #5, Funhouse Magazine. Her author interviews can be read on The Millions, Electric Literature, The Bloom and Tethered by Letters. She has performed at The Moth in NYC, is a Pushcart Nominee and a finalist for: Penelope Niven Prize in Creative Nonfiction, Cutbank Literary Journal, Bellingham Review’s Tobias Wolff, Barry Lopez Creative Nonfiction, Blue Mesa Review and The Raymond Carver Short Story.

What Happened to Letitia Elizabeth Landon? was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.