The first version of The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde that I saw was “Hyde and Go Tweet,” a 1960 Warner Bros. cartoon starring Sylvester and Tweety. My grandparents had a small collection of VHS tapes that my cousin and I would put on when we visited, and this was included in some Looney Tunes collection in a worn-out case that I would watch in fascination as Tweety transformed from a tiny and meek bird to a hulking, violent beast.

If it wasn’t “Hyde and Go Tweet,” though, it could have been “Hyde and Hare,” a 1955 Looney Tunes cartoon that shows gentle Dr Jekyll turning into a green, squat man with knuckles dragging on the ground that chases Bug Bunny with an axe.

Jekyll and Hyde adaptations are common in just about every format, from radio plays to cartoons to comics and novels. It’s been parodied endlessly, and even if you’ve never seen a movie version or read the book, you still will likely understand what people mean when they reference someone being in a Jekyll and Hyde situation with another person.

I certainly thought I knew the story. So when I was assigned it in a Victorian Literature class, I wasn’t exactly excited to pick it up. After all, when I read Dracula, I couldn’t help thinking, “You’re really not supposed to know he’s a vampire” through most of the story. Sorry Stoker fans, but I think it loses a lot of its bite when you know the ending.

Though I’d never read the book, I’d seen enough versions of it on the screen — beginning, but not ending with Looney Tunes! — that I was confident Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde would be even worse. It’s just a novella, and the big twist is that they’re the same person, which I already knew going in.

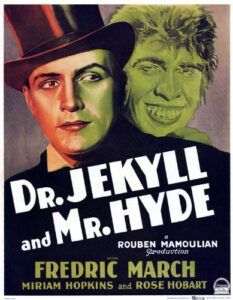

I was surprised to find out that The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde kept me riveted — and also, that Hyde was very different than adaptations led me to expect. While the exaggerated monstrosity is typical for a cartoon, even the adaptations that took themselves seriously that I had seen featured a monstrous Mr Hyde. In many, his skin is green. He often has a humped back. He is balding — or hairy — and has crooked teeth on display in a constant leer.

Let’s put a pin in the discussion of how evil/villainy is associated with disability, poverty, ugliness, and more for now. In these adaptations, Jekyll is essentially a werewolf. He is an average person who occasionally turns into a violent monster, terrifying the people around him. So it came as a surprise to come across the actual description of Hyde from the original novel:

“He is not easy to describe. There is something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, and yet I scarce know why. He must be deformed somewhere; he gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn’t specify the point. He’s an extraordinary-looking man, and yet I really can name nothing out of the way. No, sir; I can make no hand of it; I can’t describe him. And it’s not want of memory; for I declare I can see him this moment.”

While Mr. Enfield described him as looking “detestable” and says he gives the “feeling of deformity,” (there’s that ableism popping up again), he is forced to admit that there’s not anything really out of the ordinary about his appearance. He makes people feel unsettled, but it’s not because he’s a werewolf. He has some intangible quality that repulses people, but it’s not anything particular about how he looks. The only other description he receives in this first chapter is that he is a “little man” — hardly the hulking beast we see in many adaptations.

He’s later described as “small” and “plainly dressed,” “pale” with a “displeasing smile.” The book admits that “all these were points against him, but not all of these together could explain the hitherto unknown disgust, loathing, and fear with which Mr. Utterson regarded him.”

While Hyde’s appearance surprised me, his behavior unsettled me in a way I didn’t expect a horror novel from more than 100 years ago to be able to. I want to give a content warning for child harm and injury here.

The first time we see Mr Hyde described — by Mr Enfield, relating a story to Mr Utterson — he is walking down the street. When a 9-year-old girl crosses his path, running down a street, he “trampled calmly over the child’s body and left her screaming on the ground.”

When the people around, including the girl’s mother, protest in outrage, he cooly says, “‘If you choose to make capital out of this accident, I am naturally helpless. No gentleman but wishes to avoid a scene. Name your figure.” He pays off the family — the girl is shaken but not seriously hurt — and walks away.

This is leaps and bounds from the Hyde I thought I was dealing with. He isn’t an animal. He isn’t even particularly violent at this point. He’s just utterly amoral. He is simply selfish, but taken to a monstrous extreme. He cares so little about other people that he wouldn’t move a few steps out of his way to prevent from trampling a kid.

When he faces consequences, he answers like someone with status. He isn’t speaking in gibberish or even in a decreased vocabulary, as many adaptations have him do. He moves through the world with the confidence of someone untouchable, used to privilege.

Though he becomes more violent over the course of the story, this villain that we see in the first chapter is so much scarier and more relevant than the versions that resemble Frankenstein’s monster or a wild animal. This monster has much in common with a billionaire than with a werewolf. He’s not far off from many of the people we see every day who would sooner burn down the world than experience a modicum of discomfort, who have so little regard for other people that they refuse to make even the most minor of changes.

It also is much more effective as a warning for us about the sides of our personalities. I don’t much worry about becoming a slavering beast who has an insatiable appetite for violence. But the idea that there’s a part of you that is selfish and uncaring, who would distance themselves from the world rather than participate in it and all its attendant hurts and discomforts? And that it has to be kept in check before it takes over your entire being? That’s a lot closer to home.

I’m surprised at how much this story has shifted over the years to be an exaggerated, cartoonish version of itself, and it’s one of the times where it’s well worth returning to the original story. It’s just as chilling and thought-provoking today as it was when it was written. Now, I just hope that future adaptations can retain what made it so powerful in the first place.

Source : What Adaptations Get Wrong About Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde