The author talks to Javier Zamora about writing as a vehicle for political rage

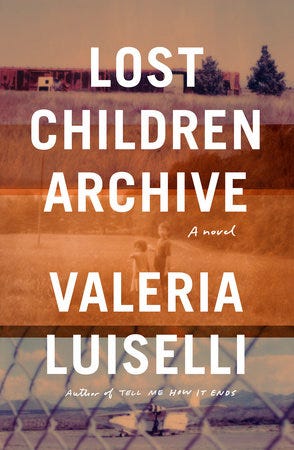

When friends ask me what Valeria Luiselli’s new novel, Lost Children Archive, is “about,” I say it’s about many things. The big theme that stands out for me is immigration — in particular, the “crisis at the border,” and more specifically, how we talk about and deal with children. The novel brilliantly reflects the pervasiveness of these issues by keeping the current crisis as background noise; Luiselli never lets it enter the main stage. Yet, immigration is only one of many themes in the book. Lost Children Archive can also be read as a critique of technology, what it means to return to radio, cassette tapes, maps, polaroids, and what this return to these older/lesser technologies tell us about our current “American experience.” Another major thread is empathy: can we really love someone else’s children as much as we care about our own biological children? Part of empathy is also listening. The novel essentially is about listening to everything around us in order to better understand the world we’re walking on.

I have been a fan of Luiselli’s work for a long time. In all of her work, there are nods to prior literary works, and in this book, she has found the right balance between the referential and the new. This is a novel that asks to be read multiple times; each time, there will be a different reading, different sounds, different pathways that can be taken with each bibliographic reference.

From her work as an immigration translator that was well captured in Tell Me How It Ends, we arrive at a work of fiction that is not about immigration but fiction with immigration — a distinction I hope writers and readers think about in a time when our media, politicians, and own interests seem to be making immigration into an obsession. I have not stopped thinking about this book, the world it builds. In the best way, Lost Children Archive has stayed with me, making me look at my own immigration story in a different way.

Javier Zamora: Your novel brilliantly captures the current immigration moment; by that I mean it addresses invisibility and hypervisibility of immigration. Could you talk about this?

Valeria Luiselli: It’s definitely not a novel about immigration, but it’s a novel with immigration. It’s a story that looks at immigration’s course and it looks at the way we can talk about political violence more generally. So one of the things that I believe as a writer is right there in the novel to a degree, or more than what I believe, it’s one of the questions that I have been asking myself now for many years. The question is this: how do you write about crisis? And in particular, about a particularly vulnerable population without doing more harm to said population?

For example — on a very basic level — does writing about undocumented children bring them into a kind of unsolicited visibility? Or does it make them more likely to become prone to become a target of political violence? So does writing about undocumented children make them more vulnerable in the context of an administration that will surely target them this way? But then not writing about them — if we all shut up and not even look — then the vulnerability is perhaps of another kind, right? Then perhaps political violence can go unseen, unreported, ignored, and ultimately with impunity, right?

I debate myself constantly between those two poles. I think that the novel is different from my essays in that it doesn’t explicitly reveal a political stance. It quests more than advocating any kind of answer.

Does writing about undocumented children bring them into a kind of unsolicited visibility? But then if we all shut up and not even look, then perhaps political violence can go unseen, unreported, ignored, and ultimately with impunity.

JZ: Regarding searching or questing, I think what I got from your book, and maybe because it was published so close to Tell Me How it Ends, I learned a lot about what I expected from a book through reading your novel. Could you talk about how you relate to expectations, both what you expect from yourself as a writer and what your readers expect from you?

VL: To be very very blunt and honest with you, I don’t think about expectation when I’m writing. Really on the day to day basis, I’m thinking about sentence structure, form, architecture, and rhythm. What I do think about when I step a little bit away — from the moment of engaging with the language and with my work — is whether the form and the vehicle which I’m using is the exactly correct one for what I’m trying to say.

What happened to me is that at some point I was writing the novel — I started writing it in the summer of 2014 — and at some point, I started to use it as a vehicle for my political rage and for my political stances and I started writing more directly about the immigration crisis within the novel.

After a while, I started to realize that I was really messing the novel up. I wasn’t really doing justice to the novel, I was kind of suffocating the prose. And I wasn’t doing justice to the issue. So I stopped writing it and I wrote Tell Me How it Ends. And it was so clear that that was the form I wanted to say had to be an essay, had to be more straightforward, had to disclose a more clear political stance as well as a positionality of where I’m writing from. I’m a member of the Hispanic community but also I am a member that came here to study a PhD but didn’t come here undocumented. So all that I could leave very clear in a very straightforward approach to the issue right? And only then was I able — when I finished Tell Me How it Ends — to go back to the novel and have a different kind of narrative distance which was just what I wanted to do in the novel.

JZ: At some point, did the political rage — some of which you say turned into Tell Me How It Ends — become the Elegies for Lost Children? Because, to me, the Elegies act as this weird, dark undercurrent. Reading them, I thought it was an actual book, as you claim, and was surprised to later learn it is your own fabrication — which is brilliant. And why the choice of creating these made-up Elegies from other literary references? Why do that? Instead of incorporating actual events, like news, in other words, a very non-fiction approach?

VL: First of all, I don’t appreciate fiction that kind of just reproduces the violence of reality or the violence that we read about. I find it a little bit parasitic and also sometimes sensationalist. There were all these novels in Mexico when the narco wars broke out and the drug wars started, I found it suffocating.

I never really wrote anything in fiction about the drug wars in Mexico. I guess Tell Me How It Ends is my best approach to it. But until time passed and writers had been finally able to take a kind of pause and a breath and a narrative distance, and then other much more interesting books about violence emerged. Like Yuri Herrera’s books, particularly one book I forgot the title right now, La transmigración de los cuerpos (The Transmigration of Bodies) I think. That’s to say, I had never really appreciated a certain kind of fiction in its approach to political violence.

I also had decided while writing Tell Me How it Ends that I didn’t want to use testimony as such — kind of just use the voice of someone who had told me their lives and reproduce it to a minor detail is also just a little bit transgressive. So Tell Me How it Ends takes bits and pieces of a person’s life — different people’s lives — but never a full testimony, and their stories somehow always visibly intertwine with my interaction with them. That same thing in the novel became pure to me.

I didn’t want to transgress. I didn’t want to appropriate. I didn’t want to reproduce, as things are reproduced in the media. So I had to find another way in. And that’s exactly what fiction is about right? Finding different ways in. The way that happened was, as things are, a little bit by coincidence and a little bit by generating the conditions for coincidences to happen, and those conditions had to do with just reading other people’s takes on different historical instances of children in situations of virtual abandonment or forced migration. And among the many many books I read, there was this book by Jerzy Andrzejewski, The Gates of Paradise, that narrated the children’s crusade in the 13th century. In a way not such a different story in its brutality to the one of children fleeing now. That gave me a way in, like a rhythm, a way of stepping one step back and again finding a narrative distance.

And I really like that you say that it is like a dark undercurrent. That is exactly how it felt writing it.

I started to use writing as a vehicle for my political rage and for my political stances.

JZ: Speaking of ways into a narrative, the cataloging, archiving, documenting, reenacting, incorporated into the text do a great job to tell the story. As a reader, I found myself going back and re-reading the elegies, going forward to see the polaroids, analyzing the “boxes” between chapters, etc. … In other words, the “form” the book takes, propels the story forward. Where did that come from and how did the “form” come together?

VL: How? Very slowly. The thing is where to start? On one hand I have always been interested in the question of how the archive that you work with or even just the materials that you work with and the space that you work in leave a print — like a fingerprint or footprint — in the work that you are producing. I mean there are many types of writers and I guess there are writers who sit in a room and are completely oblivious to every material around them and are completely into fiction. I write very different, I write with a lot of material companions, so like books and cutouts and pictures. If I work in a library, I’m constantly standing up and getting books. I think that in my book, in my work, the fingerprints of the archive always somehow show up.

In this novel I was interested in meditating about storytelling, about how we compose stories with the pieces of things we have, and how there are many ways of composing stories but we ultimately decide to arrange them and to somehow build a narrative and to mediate our relationship to the world in that narrative. Because I was interested in that question I integrated the archive of the novel very visibly.

I think that the way that you said you read is really very fortunate and gives me great joy to hear that. Because I think that is exactly how I would like to read. Because you can see this book that’s mentioned here has this echo here, and how would I as a reader recompose that? And I think that laying that archive there for others to move along also maybe creates a more active interaction between the mind of the reader and the text; because it’s read in more ways, you can shift, you doubt, you can reckon.

There are many ways of composing stories but we ultimately decide to arrange them to build a narrative and to mediate our relationship to the world in that narrative.

JZ: And the personal experience too. I also followed along with the sounds. I’m a reader that likes to listen to music while reading and I was listening to the albums mentioned in between chapters. The boxes act as the sounds that you should listen to, a sound bibliography of sorts. And regarding that, I had never listened to “Metamorphosis,” by Philip Glass, I had no idea –

VL: It’s such a beautiful piece right?

JZ: It’s absolutely beautiful. It sort of mimics, or acts, like the novel. I find “Metamorphosis,” very ironic because it ends and begins almost the same way. It’s very circular.

VL: It is, it has like a very minimalist circularity.

JZ: And that’s a huge theme, or a key, that unlocks your work. There are echoes, there are birdsongs, there are trains. Even Apacheria comes off as circular. There’s a revisionist impulse in all of this.

VL: Definitely. It’s about how we tell history, right? And therefore, how we make past as presence, so yeah there is something revisionist. A stance on a political and aesthetic. Like a very intimate stance with respect to basically how we make sense of stories in time. Reenactment has to do with it. Reenacting is on one hand a very desired cultural practice where an event, a historical event, is reproduced ad nauseam for consumption and entertainment. But in another sentiment, in another more intimate sense, it’s also a way of playing out history and maybe bringing that which is far away historically and peoples who are faraway and circumstances unreachable and bringing it intimately close. And maybe being able to experience a deeper kind of understanding and empathy through that ledge.

JZ: And speaking of very personal, the polaroids at the end, you’re probably going to get this question a lot, are those your children?

VL: So there’s one kid in the pictures right?

JZ: Yes

VL: Yeah that’s my daughter.

JZ: Was having a family, being a mother, help with the part of the book that is told via a child speaker? I ask because I’ve seen terrible examples of attempts of trying to convey childhood, myself included, and it comes off as trite. But your writing is genuine, there’s never a point in which I know an adult is writing…

VL: I think that since I became a mother like 10 years ago, I have always intimately written about childhood and children. Maybe before I did as well but differently. I spend a lot of time around children. I teach creative writing workshops in the detention center for undocumented kids. For a while I did interviews and translations in courts with kids.

I have many nephews. I only have one daughter. And I have two step-sons from my ex-partner, but they grew up with me too. So I always find myself around children. And I sense that my only way of making more sense of adulthood has had a lot to do with reconnecting to childhood, not severing the person we were — when we looked at the world the way we did when we were little — from the person that we are now. I am always trying to translate those two worlds back and forth.

INTERVIEW: Valeria Luiselli, author of Faces in the Crowd

JZ: Now I’m gonna ask a question that annoys me when others ask it, but will ask nonetheless. From my understanding you wrote this novel and Tell Me How it Ends first in English right?

VL: Yeah, I did.

JZ: So this is the second book that you begin in English if I’m not mistaken?

VL: Yeah, it is. I mean I have written many other things in English and many bits and pieces of my previous books were first in English because the notes that I think in are always bilingual. And I’m not sure if you’re fluent in Spanish, are you?

JZ: Sí.

VL: So you’ve experienced the empezamos la frase con un idioma and then you finish it in the other? Our brains, I think especially if you’re Hispanic in the US

JZ: Or everywhere…

VL: Wherever, everywhere, it’s not only that, I mean, we are a humongous community here, so it’s not like we’re on an isolated language like in Norway or something. There are at least 60 million cabrones who speak Spanish here, right? Second largest Spanish-speaking country in the world! I mean it doesn’t consider itself a Spanish speaking country for some bizarre reason, but [America] is a Hispanic country too.

Within this, I find really interesting how my brain here, even though I have maybe been bilingual since I was 5 years old — I went to American schools in Korea when I was 5 and I learned how to read and write in English before I did so in Spanish. So I haven’t been bilingual since I was born, but since I was five — but my brain never connected the two languages as absolutely as it has here in the U.S. It’s like here we have a third language here which is this confluence of both Spanish and English.

JZ: Did that help?

VL: I think it helps writing because if you are bilingual or trilingual — if you are at least bilingual, you know that certain things can feel better or more accurate in one language and not in another. So when you are forced to say it in only one of them, there’s always like this need to be more precise because that language is maybe not doing justice to what you’re trying to say exactly. So then I think that forces you to be incredibly rigorous and think things once and twice and three times and eleven thousand times until you find the exact way, which is usually, I mean there’s something very fertile in that. You’re not taking the direct route to anything, you’re always kind of meandering on until you find where you wanted to go in terms of finding meaning.

JZ: Along those lines, I really appreciate that you don’t really make that big of a deal around ethnicity or immigration status of the novel’s protagonists. It’s very subtle. There’s this almost-fear but it’s not an overwhelming fear, and it’s not this overly flat or reductive depiction of a migrant’s story in this country like how most media outlets depict immigration. I commend you for that.

And I don’t know if you know, but I immigrated and I crossed the border along the desert, and I’m just completely tired of all the narratives that are going around regarding this topic, and I’m tired of the sensationalist coverage in the media (from all political views). And I just thought your novel does a brilliant job balancing all of these things, in the background of the novel. A sort of background noise.

VL: Oh wow what an honor. Don’t say that, you’re gonna make me cry.

About the Author

Valeria Luiselli was born in Mexico City and grew up in South Korea, South Africa and India. An acclaimed writer of both fiction and nonfiction, she is the author of the essay collection Sidewalks; the novels Faces in the Crowd and The Story of My Teeth; and, most recently, Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions. She is the winner of two Los Angeles Times Book Prizes and an American Book Award, and has twice been nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Kirkus Prize. She has been a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35” honoree and the recipient of a Bearing Witness Fellowship from the Art for Justice Fund. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Granta, and McSweeney’s, among other publications, and has been translated into more than twenty languages. She lives in New York City.

About the Interviewer

Javier Zamora was born in La Herradura, El Salvador, in 1990, and he migrated to the United States in 1999. He received a BA from the University of California at Berkeley and an MFA from New York University. Zamora is the author of Unaccompanied (Copper Canyon Press, 2017). He has received fellowships from CantoMundo, Colgate University, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Poetry Foundation, among others.

Valeria Luiselli’s ‘Lost Children Archive’ is a Road Trip Novel about the Border and Its Ghosts was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Valeria Luiselli’s ‘Lost Children Archive’ is a Road Trip Novel about the Border and Its Ghosts