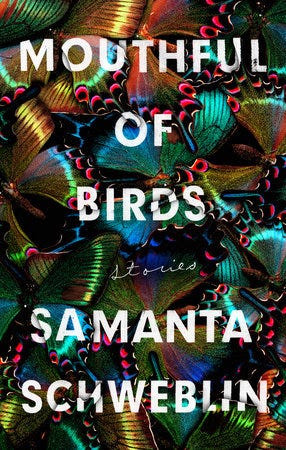

Megan McDowell on the challenges of translating strange fiction — and why it’s worth it

I n 2017, Samanta Schweblin’s novel, Fever Dream, was released in English. The surreal, hallucinatory tale about a woman dying from a mysterious poison, expertly translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell, earned a cult-like reputation among writers and raves from critics for its sparse prose and haunting tension.

Schweblin’s latest collection in English, Mouthful of Birds, also translated by McDowell, offers up twenty short stories that are just as haunting as Fever Dream.

The first story, “Headlights,” is a pitch-perfect rendering of abandoned women sobbing in a dark field. The story hints at a larger terror at its own periphery, leaving the reader in wait for something even more terrifying to happen, all while underscoring the generational tension between young women and their elders.

Other pieces examine strange almond-like pregnancies, a bizarre fight in a truckstop restaurant with a short man who has a tall dead wife, a merman, a depressed brother, and heads against concrete.

While the collection fluctuates as a whole between fully fleshed out stories and looser pieces, there is no denying the originality and darkness that defines Schweblin’s work. Even Schweblin’s less polished stories are tense wonders.

The more I read of Mouthful of Birds, the more questions I had about how it came to be in English. As translator, McDowell must also confront the darkness in Schweblin’s work, perhaps more intimately than anyone, and bring these vicious, yearning scenes to life in another language.

McDowell and I spoke via email about how she became a literary translator, why she is drawn to darkness in literature, and what’s coming next from Samanta Schweblin.

Sarah Rose Etter: What first drew you to Samanta Schweblin’s work? You’ve worked with her as a translator for two books now, so I was curious how you two found each other.

Megan McDowell: Well, I was lucky enough to be offered the translation of Distancia de Rescate (Fever Dream) when Riverhead bought it. I think it was because of a recommendation from Alejandro Zambra. Laura Perciasepe at Riverhead sent me the book and I started reading it over dinner that same evening. And once I started I couldn’t stop. I had other things to do and I had to get up early the next day, but I just couldn’t stop reading. I finished it late that night. It’s not often that a book can just take you out of your world so immediately and completely. So of course, I said yes.

Mouthful of Birds is the second book I’ve translated by Samanta, and there are two more on the way. I’m working on her second novel now, called Kentukis, and I love it — it’s creepy and surprising. After that will come her short story collection, Siete casas vacias (Seven Empty Houses), which came out in Spanish in 2015.

“Birds in the Mouth” by Samanta Schweblin

SRE: I wasn’t planning to ask about the next work coming out yet, but I can’t help myself. You have to tell us a little bit about Kentukis and Siete cases vacias. Just a tiny bit about each?

MM: Kentukis is Samanta’s new novel that just came out a month or two ago. It’s very different from Fever Dream, but just as compelling. It’s structured as many interwoven stories of people from vastly different backgrounds living all around the world. It’s an exploration of the way technology has of infantilizing us as we incorporate it into our daily lives, how even as it offers us new possibilities and abilities, it also tends to narrow our perspective and make us grow complacent.

As of now, the book’s opening line in English is: “The first thing they did was show their tits.”

Siete casas is, as I said, short stories, only seven of them as the title suggests. Like Mouthful of Birds, these stories have a precision and weirdness that disorients and intrigues; they tend to center on domestic worlds that are distorted in a way that makes the reader question any sense of security she may have. Here are seven first lines:

“We’re lost,” says my mother.

“Where are your parents’ clothes?” asks Marga.

Mr. Weimer is knocking at the door of my house.

The list was part of a plan: Lola suspected that her life had been too long, too simple and light, and now it lacked the weight that would make it disappear.

My mother-in-law wants me to buy some aspirin.

The day I turned eight, my sister — who absolutely always had to be the centre of attention — swallowed an entire cup of bleach.

Three lighting bolts illuminate the night, and I catch a glimpse of some dirty terraces and the buildings’ partition walls.

SRE: Those lines are incredible — especially the cup of bleach line. Very excited to hear both of those are in the works. But let’s focus on Mouthful of Birds. How did you feel when you first read Mouthful of Birds?

MM: I’ve always had a soft spot for dark literature, psychological horror, stories that make us uncomfortable when we read them. Samanta is a master of that, without relying on any genre tropes. Her work is genuinely surprising and thought-provoking.

When I translate a book or story I have to read it over and over, and I never get tired of reading Samanta’s work. I get something new out of it every time, change my interpretation a little, pick up on something I hadn’t before. That kind of writer is a joy to work with.

I also love short stories. I’ve never understood why they get such a bad rap in the publishing world. And the short story is Samanta’s terrain, she’s very sure-footed and she knows how to pace a tale. Each time you finish one you get a little gleam of satisfaction along with the sense of unease her work tends to provoke.

There isn’t a clear path to becoming a literary translator. It’s always a little hazy how one gets into such a thing, and you don’t really know until you’re doing it.

SRE: What drew you to dark literature specifically for translation? Is that something you’ve always been interested in since you began reading?

MM: I remember when I was a kid, I loved to read mystery, thriller, and horror books. My dad and sister read them too, and we used to pass the Stephen King novels around. I would also take whatever books looked interesting from my parents’ shelves, and they weren’t always age-appropriate.

Now, I grew up Catholic, and I have a deeply ingrained sense of guilt. I remember reading a book from my dad’s shelf that I was definitely too young for, a lot of violence and sex. I knew I shouldn’t be reading it and I felt guilty, but I also couldn’t stop.

Maybe that was among my first transgressions; it was exciting. Later I started reading more literary books, but I never lost the taste for darkness. When I discover writers who can combine the transgressive joy of horror with literary depth and original style, I’m sold.

SRE: When did you first know you wanted to become a translator? How did you get into it?

MM: It was a cool morning in March of 1999, 8:55 in the morning, over coffee. Just kidding!

It was a gradual process, starting with a general interest in reading translation, then in publishing, finally in being a translator myself. I was interested in translation as a genre before I knew another language. I loved to read books from other countries, I always had the feeling I was getting some kind of privileged, rare look into other patterns of thinking.

At first I was interested in publishing — as an undergrad I interned at a small press in Chicago called Ivan R. Dee, and after I graduated I had a year-long fellowship at Dalkey Archive. That job gave me the idea that knowing another language would help me get a job in publishing, so I moved to Chile to learn Spanish, and then for a while I worked as a translator at a British shipping company in Valparaíso. I really learned a lot, but eventually I felt stuck because I wanted to work with literature, not insurance reports, and so I moved back to the states and started a Master’s degree focused on literary translation at the University of Texas at Dallas.

But even when I went back to school for translation, I wasn’t really sure I could do it. It was all more of an exploration or a testing of the waters.

Maybe the answer is that my desire to be a translator was concretized when I published my first translation — that was when it was really real. It’s strange because there isn’t a clear path to becoming a literary translator, it’s always a little hazy how one gets into such a thing, and you don’t really know until you’re doing it.

A translator spends a lot of time trying to figure out what a writer really means, what lies behind the words and makes them move, similar to what a therapist does.

SRE: Can you tell me a bit about the first book you translated?

MM: I took some translation workshops and the project I worked on was Alejandro Zambra’s The Private Lives of Trees. I read from my translation at the ALTA conference that year, and one of the three people in the audience was Chad Post from Open Letter (I knew him from the old days at Dalkey).

Later, when Chad was considering the book, he remembered I was working on it, and he ended up publishing my translation. I think I was very lucky in many ways in the whole process, a lot of things came together to make the publication possible.

SRE: What kind of relationship do you have with Samanta as a result of these translations? What is it like to work with her?

MM: I’ve only met her twice in person, once in London for the Booker madness, and once when she was passing through Santiago and came over for dinner. But we’ve been in contact much more and I do feel close to her; maybe it’s just that I admire her a lot, but I’ve also spent a lot of time in her head, which makes me feel, maybe falsely, that I know her well.

If you translate living writers I think it’s not unusual for authors and translators to be pretty close. It’s a strange and intense relationship. Right now I’m finishing up the translation of an essay on translation and language by Alejandro Zambra. It’s even more meta than it sounds, because I have a cameo in the essay, and I recognize points in it that grew out of things that he and I have talked about.

He also references a book by Adam Phillips that compares translation to therapy. There are a lot of conclusions one can draw about the very possibility of “translating a person,” but the comparison to therapy rings true: a translator spends a lot of time trying to figure out what a writer really means, what lies behind the words and makes them move, similar to what a therapist does.

Samanta Schweblin’s ‘Mouthful of Birds’ is a Dark Magical Nightmare

SRE: What else are you working on translating beyond Samanta’s work? What are you reading right now that’s really compelling?

MM: I’m working on several things. I’m in the final stages on two books: one is a book of short stories called Humiliation by Paulina Flores, a young Chilean writer. The book was a big hit in Chile and I’m excited to see it in English; it’s rare for a first book to be translated, especially if it’s stories, and I think that speaks to the quality of the book and also the eye of the editors (One World in the U.K. and Catapult in the U.S.).

The other is a novel by an Argentine writer, Nicolás Giacobone. This is his first novel, he’s previously been a screenwriter — he wrote the script for Birdman, for example. It’s a strange and compelling novel about a screenwriter who is kidnapped by a great director who keeps him in the basement and forces him to write award-winning screenplays.

Then I’m in the beginning stages of two other novels: Kentukis, which I’ve already mentioned, and Museo animal, by Carlos Fonseca, both of which I’m excited about.

As for what I’m reading, strangely it’s a lot of non-fiction (unusual for me). I’ve just finished a book called Cuaderno de faros by Jazmina Barrera, a young Mexican author. It’s a beautiful and surprisingly personal collection of essays about lighthouses, and the writing is assured and understated. I’m also reading Alguien camina sobre tu tumba by Mariana Enriquez, which is a book of essays on the author’s visits to cemeteries around the world. It’s creepy and entertaining, like you’d expect from Mariana.

Finally I’m reading Rebaño, by the Chilean journalist Óscar Contardo, which is about the Catholic church’s abuse of power in Chile. Also very well-written, and it’s helping explain the context of how and why those kinds of atrocities were particularly possible in Chile, where priests have typically had a kind of god-like status in public life and in the daily lives of their parishioners.

SRE: What do you love about Humiliation by Flores? You sound so excited about it. What can we expect from that work?

MM: The stories in Humiliation have a lot of sensitivity and wisdom. They often seem like small stories and when you read them you think you know where they’re taking you, and then you end up somewhere entirely different. The book is very Chilean in its evocation of place and class and childhood, but it has a wider reach. I think Flores is a real writer and I’m excited also to see what she does next.

SRE: When you’re deciding on a translation project, what helps you choose work? You live in Chile and focus on Latin American writers. What draws you to that region? What do you like about what is happening in literature there?

MM: I learned Spanish in Chile and I live there, and it’s the Spanish I feel most comfortable with. It’s also kind of my adopted country, and I know more about the history and the literary scene. I’ve expanded my reach into Argentina, which is close by and shares a lot with Chile, and I want to expand further. In 2018, I went to Colombia and Mexico, and I would love to translate some authors from those countries, we’ll see how that works out.

I don’t know that I can say I really choose a project — a lot of the time the project chooses me. The only writer I really chose 100% was Zambra with the first book I translated, and I hit the jackpot there. These days, there’s a different story for how I come to translate each book I do. Sometimes the editor offers me a book, and if I love it I say yes. Other times I’m the one telling editors about a book I love; sometimes I spend years talking a project up before it comes to fruition. Also, once I translate an author, I’m committed to them. I try to translate everything they do, which means I can’t always take on new projects.

I do think that the English-speaking world can be a bit xenophobic. Reading translation is a fun way to combat those tendencies.

SRE: In terms of the state of translation, can you talk about why it’s so critical for these works to make their way into English?

MM: I’ve been putting off answering this question because there’s just so much that could go into my reply.

Of course, I dothink it’s critical for works to be translated, but there are a lot of people who don’t. I often get asked why people should read in translation, when there are so many great works written and being written in English; I’m always astonished by that question. But I try to avoid saying that people should read translations, because reading should never be prescriptive or obligatory.

I can say that for me, I feel like reading in translation broadens my sphere of empathy. Reading in general gives people compassion by letting them experience the subjectivities of other people (authors, characters), and reading literature from other cultures makes that possible empathy a little larger, I think. I also believe that translation adds to the English language. I know people always talk about what is lost in translation, but so little attention is paid to the vast amount that is gained — a whole new work that wasn’t in English before, one that draws on other histories and traditions, one that can influence writers and open up new paths for them.

But getting back to the point about empathy, I do think that the English-speaking world can be a bit xenophobic, sometimes overtly and other times in very subtle ways. Reading translation is a fun way to combat those tendencies. I guarantee that if you compared the circle of translation readers to that of Trump voters, there would be little to no overlap.

I am optimistic about the state of translation. I see more and more people who are curious and knowledgeable about international literature, and there are ever more presses that are either specifically interested in translation or becoming more open to it. There are a lot of conflicting currents in the world today, and the one carrying translated literature is small but I think it’s growing; hopefully it will become an ever-larger wave.

About the Translator

Megan McDowell has translated many contemporary authors from Latin America and Spain, including Alejandro Zambra, Samanta Schweblin, Mariana Enriquez, Gonzalo Torné, Lina Meruane, Diego Zuñiga, and Carlos Fonseca. Her translations have been published in The New Yorker, Tin House, The Paris Review, Harper’s, McSweeney’s, Words Without Borders, and Vice, among others.

About the Interviewer

Sarah Rose Etter’s first novel, The Book of X, is forthcoming from Two Dollar Radio. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Cut, VICE, Guernica, Philadelphia Weekly, The Fanzine, and more. She is the recipient of writing residencies at the Disquiet International Program in Portugal, and the Gullkistan Creative Program in Iceland. In 2018, she was the keynote speaker at the Society for the Study of American Women Writers, where she presented on surrealism in fiction as a mode of feminism.

Translating the Dark Surrealism of Samanta Schweblin’s “Mouthful of Birds” was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Translating the Dark Surrealism of Samanta Schweblin’s “Mouthful of Birds”