Cartoonist Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom begins her graphic memoir, Palimpsest: Documents from a Korean Adoption, with the following dedication:

This album is dedicated to all adoptees

—living and dead—

whose voices have been silenced

What follows is the story of how Sjöblom, adopted and raised by a family in Sweden, discovers a document that unravels everything she had been told to believe about her own history as an orphan. She recounts every difficult aspect of the investigation on the path to uncover the complicated truth about who really owns the story of adoption.

My interview with Sjöblom over video chat ranged far and wide, from her signature art-style to Sweden’s adoption lobby, from the female adoptee body to misconceptions about reunions, mental health, and first mothers.

Marci Cancio-Bello: Would you be able to talk about showing your reunion with your birth mother?

Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom: Yes. It was very difficult to write. We have a television program in Sweden called Without a Trace. It’s an entertainment show for the general audience to watch painful reunions between adoptees and their first parents and siblings. The narrative always, always ends with the adoptee, alone again, on her way home or something, saying, “Now I feel whole, now I feel like this part of me has been found, and I can be a normal person again.” There is this sense of catharsis and relief, and that everything is fine. This is what the program wants it to be, and what the Swedish audience needs to hear as well—that reunions are considered a finale, the closing of a chapter.

I have known hardly any adoptees who have said that about their reunions. Reunions are the beginning of something. Maybe a new relationship. But so many adoptees are really, really frustrated because they feel that the initial meeting may have been wonderful, but then it becomes another relationship full of trauma and questions. It’s not easy, and it’s definitely not as it’s depicted on television and film.

I wanted to show that this is a different ending, that this is not what you think this book is going to be. It’s not the happy ending where I found the final piece of the puzzle. From the reunion comes more pain and more questions, and the reunion isn’t over. My Korean mother and I didn’t really reunite, either. We met, but we didn’t talk that much. I didn’t find out that much, so I still feel like I’m just waiting to find her, still, in a way. But as a person, not as a physical person.

When we think about a reunion, before they ever happen, it’s about the physicality of the reunion, holding, seeing, wondering where you got your features from and all that, but then after that, it becomes about the person behind the face, who are they, why did they do this, why did this happen, and it’s also about the relatives around them, why did my grandmother decide to force my mother to give me up, blah blah blah. All these questions. So I left a lot out, but I still wanted to communicate that reunions are really, really difficult for everyone involved. I didn’t want anyone to feel comfortable at the end.

MCB: Can you talk about why, toward the end of the book, you dedicated a few panels to showing how you spent your last few days in Korea, going to parks, spending time with your host family?

LWRS: I had a lot of fears when I made this book, and they kept changing when I was working on it, and of course I also had this fear that people would judge Korea, because I am very tough on Korea as the sending country. There’s a lot of prejudice about East Asian families, because one of the common images is that they are really ruthless, and the mothers are heartless and only want their children to succeed, and they push them to their limits, and they beat the children and all those things.

I wanted to show that Koreans are just like anybody else, that they are all different. We have these horrible Koreans in the agency and in City Hall, and then we have the wonderful, warm police officer who was helping me as much as she could, and then we have Min-Jeong, my translator and friend, whose whole family took us in. Her parents sort of became my children’s grandparents, so these final panels were to show that there are more sides to Korean families than just my mother’s. I also wanted to show that my trip to Korea wasn’t just painful, that there were a lot of happy, lovely memories from that too, and that we got something of a family, even if it wasn’t my biological family.

MCB: I hope this is not an inappropriate question, but do you regret having gone through the process, or are you glad you did it?

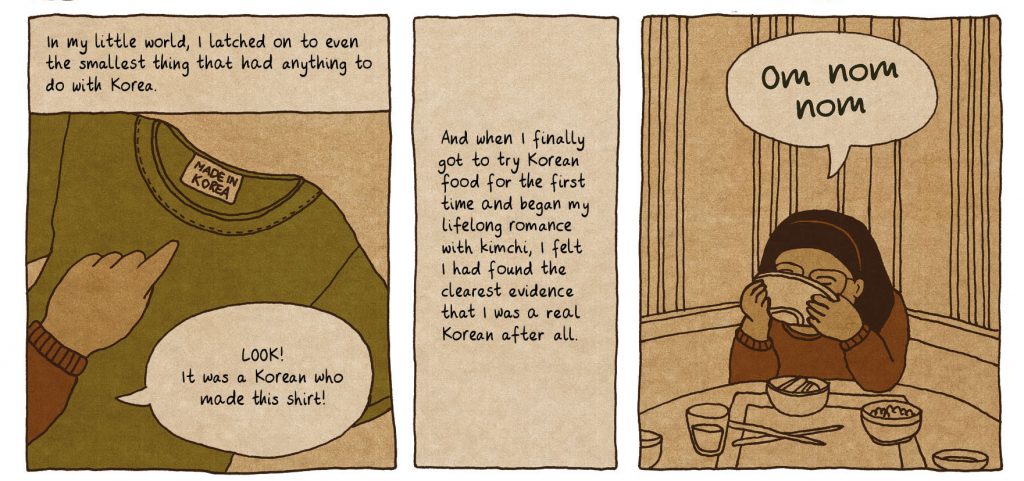

LWRS: I’m really glad I did it. Maybe not so much on a personal level, but more as an activist. I think that a lot of people who identify with my struggles in the book and see that a lot of the things that I struggled with growing up was about trying not to be Asian, not to be an adoptee, trying to be white, trying desperately to fit into something that I could never fit into. I think that my search made me also come to terms with and deal with a lot of other things about being adopted that weren’t so much about where I come from, but rather who I am now.

Birth mothers tend to be reduced to selfless angels or broken bad people. They are never seen as whole people.

It took me over 30 years to just accept the fact that I’m Asian. I finally feel comfortable with that. I don’t feel disappointed when I see myself in a mirror, or I feel disappointed, but on my own terms. But I don’t feel anymore that I wish I was blond, or that I wish I had blue eyes. I can acknowledge a lot of things that I had just been pushing down in my desperate need to fit into all these narratives about what I’m supposed to be as an adoptee.

I thought the search was just about the search. But coming to terms with being Asian has been a major thing that also made me a better activist. I think it made me a better person as well. And I think I can be a better mother to my children, because if I’m proud of being Asian, I’m not going to make them feel bad about having inherited their looks from me. So there’s so much else to it than just the search. So yeah, I’m very happy with it, even though it brought about a lot of pain, but the pain hasn’t changed.

I don’t think there is any: “You have to do this, or you have to do that.” It can be difficult enough to know what you want. If you don’t feel comfortable searching, then wait. There is only one thing you have to do, which is to try to listen to yourself.

MCB: Could you talk about your artistic process and art style? It’s so striking.

LWRS: The color scheme itself is something I’ve worked with for a long time. It has become a bit of a signum for me. Before I drew this book, I drew comics for children using the same color palette. I’m really into nature palettes with lots of browns and mossy greens. I knew that I didn’t want it to be black and white, even though it would have taken me a lot less time to not have to color in every panel. The term “palimpsest” came to me very early, long before the actual story fell into place. And since “palimpsest” refers to old parchment, I wanted to communicate that sense of fading, old paper.

MCB: You also include a lot of text, since you’re working with so much documentation of research and correspondence, but it doesn’t visually bog down the narrative. It’s fluid and well-balanced.

LWRS: I think that my work as an illustrator comes through, because some panels are more like illustrations than comic panels, and I think it works quite well because sometimes you need a break when you’re reading a comic book. The story itself has been compared to a detective story. I think that is what makes it possible to have that much text. There is so much to tell, and certain things are impossible to communicate with images. Like the emails, for example; they’re important because there’s so much frustration—and lies—in the emails that I couldn’t leave them out without compromising what I wanted to do and say. Even with the factual bits of information about the adoption industry, it’s not so much about my own adoption but about the things I discovered that are important. Where the panels are more like illustrations, as a reader you might be able to pause a bit and realize, “Oh gosh, this is huge; it’s not just her story.”

MCB: It allows you to control the pacing so readers can’t just skim through the emotionality and historicity. These pauses made me read the book carefully.

LWRS: When I found out about my paperwork, I did exactly what I show in the book. I started Googling people, and this massive thing happened: I discovered that there is this term, “paper orphan,” to begin with, and that there is massive corruption in adoption, so my search was interrupted by this other insight.

We adoptees are the ones who are punished by society for not being as ‘good’ as we were expected to be.

On the one hand, I was being very self-centered and thinking about my own story, and then learning about all these other broken families, other adoptees who were searching in vain and discovering that they had been stolen. So it felt like I had to deal with discoveries about my own story, and then all these other people’s stories as well, and I didn’t want to leave them behind.

MCB: I loved the motifs of the umbilical cord, the family tree, and the cover art depicting the Korean peninsula as a womb. As a female adoptee whose body holds the possibility to carry a child, it felt important to able to read about someone who has concerns about becoming a mother and creating literal blood ties. People don’t really talk about that sort of thing with adoptees.

LWRS: Absolutely. I think it came from different places, but I remember when I got pregnant, I felt ashamed and guilty for having thought that my mother had made an easy choice just because that’s what I’d been told. I know that’s impossible, it wasn’t my own fault, but I felt very deceived by other people who would say, “They gave you up because they loved you so much.” And then you think, “Okay, well that’s nice,” and then they can move on. Like the letter from the adoption agency that opens the book, which says that hopefully my Korean mother has a husband and new children and a good life. I had reduced her story very much to “She had me, and then she couldn’t take care of me, and was given a solution through adoption.”

When I got pregnant, this storm of emotions just hit me, physically and mentally. It’s not just about adoption, because all my friends who have been pregnant have said the same thing: how you go through the pains of birth, and how connected you are to the kid. I felt so ashamed for having reduced pregnancy and birth to something extremely simple. Of course, you can never understand those things until you’ve gone through it yourself.

We take for granted that the female body can do this, and we see this in the surrogacy industry too. It’s reduced to something that is almost not even part of yourself—that’s why you can rent a womb today, and it’s not part of the body, it’s not essential; it’s just a function of the body, like going to the toilet or something.

So I think those bits in the book are a way for me to apologize. It’s massive, becoming a mother, even if you can’t keep your child, or don’t want to keep your child. It’s massive for the baby, too. It’s quite a thing to be ripped apart from the only person you know. That’s also something that is being reduced to being meaningless.

MCB: When I read about how you had such anxiety during your pregnancy, I was reminded that this is not something women have space to talk about, especially adopted women who must struggle with particular anxieties about motherhood.

LWRS: We are reminded by maternity care. In one of the first pages, my midwife tells me to talk to my mother about my birth, because we inherit from our mothers. For them, it’s just something they say because it’s a good recommendation, but for me, a whole trauma was being unraveled in that one little detail. I can’t talk to my mother. I don’t know who she is. We also can’t talk to our adopted mothers about it, not just because they may not have experienced childbirth, but also because there can be jealousy, and guilt as well.

I struggled with trying not to be Asian, not to be an adoptee, trying to be white, to be something that I could never fit into.

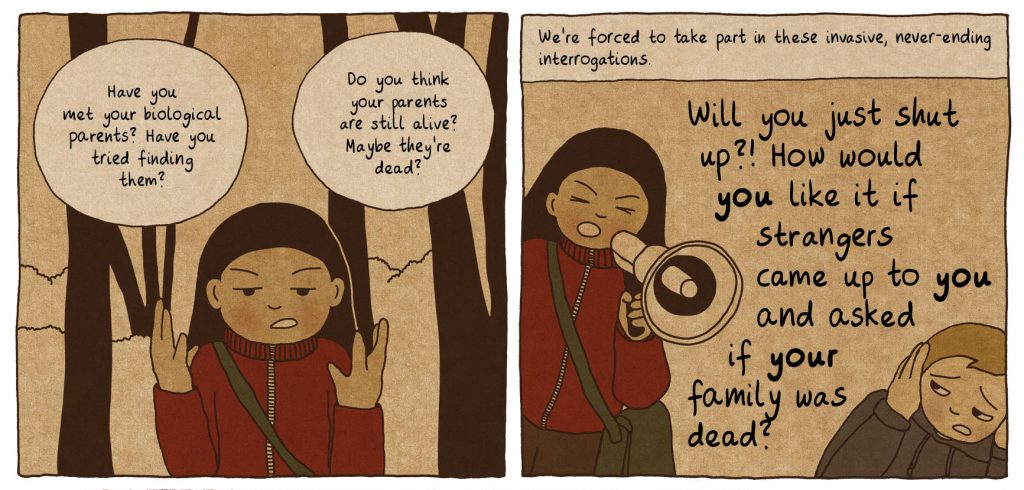

You have to fill in all this paperwork about degenerative diseases, and you have no information, there’s so much going on inside and out, and when people who don’t know they’re talking to an adoptee, they don’t understand that these questions can feel very blunt, and you can be emotionally unprepared to deal with that.

In Sweden, if you have been through sexual violence, or if your parents have died, you’re offered special help when you get pregnant; but they don’t have it for adoptees. I’m advocating for a lot more support for adoptees. So many adopted mothers in Sweden contacted me after the book was written, and said, “I know exactly what you’re talking about. It was awful, it was difficult, and I could have dealt with this much more if anyone had told me that I should be prepared as an adoptee for all the trauma that can come back to me when I get pregnant.”

MCB: And yet you didn’t do as many people tend to do, which is to demonize the birth mother. You saw and acknowledged your own birth mother as a complex person, even before you began your search.

LWRS: In Sweden, birth mothers tend to be reduced to children, or selfless angels, or broken drug-addict alcoholics who couldn’t mother because they were bad people. They are never whole people, and they’re simplified a lot.

I wanted my book to show respect for the first mothers, and to give them the complexity that they are never given in Sweden. Adoptive parents and adoption organizations have been talking for adoptees and reducing us to very simplified beings. I didn’t want to make the same mistake with the first mothers, so I didn’t want to make any assumptions other than asking questions in the book: “How did it feel for you? Were you lonely? Was it difficult for you?” and not saying, “It must have been difficult, it must have been [____],” but asking open questions in the panels to my mother.

There are things that I have left out in the story because I didn’t want any reader to demonize her or to think, “Look at this woman; be glad you didn’t have to grow up with her.” It was a difficult reunion, but with all that trauma, could it have been an easier reunion? I don’t want to put that responsibility on my mother, no matter how hurt I was, to communicate something that would paint her in a bad light.

MCB: I also appreciate how transparent you were about struggling with depression and mental health as a young person. I don’t know about Sweden, but America often shies away from anything that has to do with mental health.

LWRS: Yes, the same in Sweden, at least when it comes to adoptees. The adoption issue in Sweden is so connected to the adoption lobby that anything negative is automatically seen as political and anti-adoption. One of the first questions I get, not just about the book, but about my search or anything, is, “How did your adoptive parents react?” Everybody is so concerned about how they feel, and not: “What did it feel like for you to find your parents?” Always the first question is about my adoptive parents.

And that is a bit how it is in general for Sweden. If we voice our concerns as adoptees about our health, and we don’t get the proper care that we need, people say this must be so hard for our parents. We are the ones who are dying. We are the ones who are committing suicide, and we are the ones who are punished by society for not being as “good” as we were expected to be, and yet everybody is concerned about the adoptive parents, because they did everything they could, and now we are ungrateful because we’re not healthy enough or whatever. It’s absolutely insane.

When other Swedes commit suicide, we see it as a huge health problem that needs to be dealt with, but adoptees are not included. We have this group called Suicide Zero, which I work with, and which works to inform about suicide factors, where you can get help. They’ve listed high-risk groups on their webpage, such as LGBTQ people, refugees, and so on, but adoptees are not mentioned, even though we are the group with the highest suicide rates in society. There’s quite a lot of research done in several countries that match the numbers that we found in Sweden. The numbers are alarming, and yet if you try to talk about these things, people actually say, even in adoption organizations, “Yeah, but this is good, because it means that so many adoptees actually survive.”

We are overrepresented when it comes to foster care, crimes, suicide, attempted suicide, psychiatric care, we do worse at school, we don’t marry as much as the non-adopted population, we don’t have kids at the same rate, and all of this is dismissed, because we are told to look first at the adoptees who succeed, we should look at those who didn’t get adopted in their own countries, and be grateful for what we got.

MCB: Does Sweden have citizenship issues in the adoptee communities? Adoptees are not included or acknowledged in conversations about citizenship and immigration.

LWRS: No, we don’t have that, so that’s one of the few good things. Several of us who are activists are working to make people understand that we are migrants. I don’t know if in the U.S. adoptees are included in the term “migrants.” They may be in numbers and statistics and academic environments, but not in the general conversation. We are separated from other immigrants. So we say adoptees and immigrants. But we are trying to say that we are also migrants in this country, which is important to understand for several reasons. It doesn’t make any sense at all, but it’s because the term “immigrant” has become loaded with a lot of other things.

The adoption lobby also wants to cover up that it is an immigration issue. They want adoption to be seen solely as a bi-political thing, and it’s all about forming families, especially for childless couples to be able to have children. That’s where they want the focus to be, and not on the fact that we are forced migrants from a different country, because then the conversation would look very different. We have political parties with racist policies that want to limit the migrations, but they want to support more foreign adoptions, separating the issue that you have this kind of immigration that is welcome, and then you have the other migration that you want to stop, but they don’t realize that it’s all the same.

The whole difference is that adoptees are wanted by wealthy Swedes, and we come without our parents, whereas other migrants might come over with their families, which they want to stop. An effective way for them to distinguish between us is to not acknowledge that we are all migrants, and to just talk about us in different terms so that it’s not obvious that they are completely hypocritical about migration issues.

The post This Graphic Memoir About Adoption Isn’t Interested in Comfortable Answers appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : This Graphic Memoir About Adoption Isn’t Interested in Comfortable Answers