Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings from the Me Too Movement, a multi-genre anthology of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry that I compiled and edited for McSweeney’s, was released in September and is now headed toward its third printing. Recently, after returning home to Brooklyn from book-event travels on behalf of Indelible, I invited two of the book’s contributors—Mecca Jamilah Sullivan and Diana Spechler—to discuss the current state of the #MeToo movement and their experience writing on this topic.

Shelly Oria: Had you written #MeToo before or was this your first time writing about this topic?

Diana Spechler: The #MeToo movement has given me a new lens through which to see so much of my past, including my past writing. Sometimes the lens makes me wince. For example, years ago I wrote fairly straight journalism about pick-up artists, giving very little thought to how gross “pick-up art” is. Please don’t Google that! Or, if you Google it, please say aloud to yourself, “Well, Diana has certainly matured since 2009!” I now realize how much my experience as a woman in a patriarchal society has impacted my writing, my life, my preoccupations, my fears, my sense of accomplishment, so perhaps it’s fair to say that everything I’ve ever written has been a #MeToo piece; I just often didn’t realize it.

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan: Exactly. I’ve never written about sexual violence expressly in the context of #MeToo, but the movement has absolutely awakened me to themes of sexual harm, power, and vulnerability, both in my work and in the writing I love. I have always known sexuality and power to be important concerns of my work, and of feminist and black feminist literatures, but #MeToo has really brought these themes into a kind of focus in ways that are challenging but crucial. Or crucial because they are challenging. This movement has shown me how true it is that we can’t think about, for example, coming-of-age fiction, or what people call “domestic fiction”—or really any story that wants to deal honsetly with the experiences of women and people of marginalized genders—without thinking about vulnerability to sexual violence and sexual power. It’s there in the novels, the stories; we just haven’t all been talking about it.

DS: Shelly, I know that your writing has explored power, gender, identity, and sexuality for a very long time. How did #MeToo (at least as it reemerged a couple years ago, more than a decade after Tarana Burke started it) impact your work?

SO: I had this moment when I was asked in an interview for Indelible if I was also working on my own #MeToo story collection, and I started and restarted my answer a bunch of times—luckily this was over email—because I kept thinking of another story of mine and another that is actually about sexual violence in some way…I started with an answer that could be summed up as “not really,” and ended with some like “I’ve been writing a lot of MeToo fiction.” So I very much relate to what you’re both saying here. I think it’s mostly my thinking about my work that has shifted in the past two years, as the cultural context for everything being written and made has reshaped itself.

This change affects what’s being published, and it affects how readers are receiving these stories. If you’d written about this topic prior to October 2017—pre-Harvey—did the experience feel different in any way? Was the reception of the work different?

DS: So much has shifted since the rise of Trump. We couldn’t have gotten to Harvey had Trump not already begun contaminating the air. And I would say that that contamination has made everything feel different.

I’m not really answering the question, am I? I think that’s because what’s more compelling to me than changing reactions to my own work is how reactions to other writers’ work have changed. For example, in 1998, Joyce Maynard published her memoir At Home in the World, about how J.D. Salinger preyed on her when she was a college student. The response to that publication was ostracism from much of the literary community. I met Joyce a couple years ago at a writers’ conference and gushed about that book to her and then we talked about how different the reception would likely be today, how awful the reaction was back then, and how fascinating it is that a book that once made her a pariah could have 20 years later made her a hero. Since that conversation, I’ve seen a bit of a revival of that book. People are reading it differently now.

An even more fascinating example, though it’s not a literary example, is how the world has begun treating Monica Lewinsky. In the ’90s, she was Public Enemy No. 1. Now that seems totally absurd. Why the hell were we blaming her? Today she’s one of our spokeswomen.

I keep wanting to apologize for going off on tangents instead of answering the question, but that would be ironic since Harvey Weinstein and Donald Trump have rested their careers on never apologizing and they are rapists, while I am just a lady with an imperfect attention span.

MJS: But also, it makes sense to resist a linear narrative of time and “attention span,” as Diana puts it so well, in this conversation. I think it’s important to acknowledge how even imagining the public conversations on Weinstein (or Trump) as a kind of catalyzing or originating moment in the #MeToo conversation ends up enacting (or at least permitting) another kind of narrative violence that not only erases the labor of black women and women of color organizers like Tarana Burke, who founded the #MeToo movement in 2006, but that also centers these men and their actions, rather than the cultures of power that have allowed these stories and billions of others exist as open secrets—or at least as secreted, as objects of a rigorously selective hearing—for decades or more, and the many women writers around the world who have been telling these stories for just as long, often only to be ignored or punished or both. That’s a harder set of questions to grapple with, and one that a singularly-focused origin story can’t really accommodate.

DS: Shelly, this makes me think of this line from “But We Will Win,” your short story in the anthology: “My point was to bring attention to the larger issue.” In the context of the narrative, the sentence is very funny, but when I read it, it jumped out at me because it also could have been a summary of the activism you did by compiling this anthology. It makes me misty-eyed to think that all of our stories and poems and essays might “bring attention to the larger issue,” might help us to one day “win.” How do you view our responsibility as writers and artists in this critical moment?

SO: Working on Indelible—compiling the book, editing the pieces—felt like an effort to “bring attention to the larger issue” for sure, yes. And that effort presented itself in my life at a time when I was desperate to do something that might “matter.” Having grown up in Israel, I find protesting hard, at times impossible; I grew up believing this type of action mattered, and while my brain still believes that, my body hasn’t in many years. So putting together this book felt like the type of protest I could show up for again and again.

But really—and this may sound…hokey—I think our responsibility as artists is only to truth and vulnerability. When we meet that responsibility in a real way, the rest takes care of itself. So while conceptualizing our writing as activism is generally a bad idea, sometimes some form of activism will happen through the work nonetheless. Honesty is radical. Especially right now.

I see Indelible as part of a wave of books that are coming out now, at the two-year mark of the movement in its current incarnation and the one-year mark of the Kavanaugh hearings, and that’s been making me think a lot about this question, and specifically about the role books like Indelible play, both in readers’ and writers’ lives, in shaping the larger conversation.

Were you already working on the piece you contributed to Indelible when I reached out to you, or did the solicitation from McSweeney’s inspire the work?

DS: When you solicited me, I had a complicated reaction. Reflecting on men who have bulldozed my boundaries generated an elixir of pain, shame, and fury. Simultaneously, I was excited to contribute to such a beautiful project and terrified that I was going to fail. (To be fair, my initial reaction to every assignment I’ve ever gotten in my life is that I’m going to fail.) And then within a week or so, the voice of the piece popped into my head. It was the voice of an interrogator—a man demanding that a woman prove her allegations against her various sexual harassers. It was a silly voice, a caricature, like the collective voice that yells about “due process” these days without having any idea what it is.

That’s how writing works for me: Someone whispers a line into my ear and that’s the seed. It’s planted. Then I have to sit down and…I don’t understand gardening, so please don’t make me continue this metaphor. But eventually there’s a big, published plant?

MJS: That’s really interesting. I had mixed feelings too, actually, though I think for different reasons. I have taken issue with the way #MeToo has often been framed as a kind of spontaneous eruption of voicing catalyzed by famous or well-off white women. So, I thought it was really important to contribute, and I was honored to be invited. At the same time, it was important to me to be able to be clear about this erasure. So when we did our Philly launch event in October, It was important to me to read from Burke’s piece, “MeToo is a Movement, Not a Moment,” instead of sharing only my own writing. I appreciated the chance to center her voice in the conversation.

But your initial email about the anthology got me thinking about my writing (and, again, the literature I love and teach) in a different way. As a fiction writer, I thought at first that I didn’t have a “MeToo story,” proper, to contribute; I’ve only written a few stories that I think of as dealing directly with sexual violence, and they had been published already. But when I thought more about it, I realized that so much of my work is tinged with the specter of sexual vulnerability and sexual harm in complex ways. The story I ended up sending narrates a similar experience. The character, a thick black girl who has fought hard to lose weight, does not see herself as having experienced sexual violence—at least not at first. She doesn’t have language to describe her experience, just as she doesn’t have language to describe her body. We catch her in that search for words and context. It’s a complicated thing to grapple with, and I was glad for the chance to do it.

DS: Have either of you felt emboldened as writers because so much of the misogyny that used to be confined to whisper networks is now out in the open? How so?

MJS: In some ways, I think I have tended to be a little…what…oblivious, or maybe irreverent, when it comes to sex and power and bodily experience in my writing, and how it will be received. For better and for worse. So I don’t know that my writing has changed, but it is interesting and, I think, heartening to imagine that there is a widening readership for candid, direct, work on these subjects. How about you?

SO: I think touring with the anthology has emboldened me: meeting and talking to many people in different parts of the country who shared their stories with me, who came to our events because—whether they feel empowered or not—they are dedicated to speaking up and reading and in many cases writing, too, about this issue. I think it’s necessary. I think that in our lifetime, it will never not be necessary, and never not radical.

I, too, have been focused on the exclusion and erasure that were part of the phenomenon of the past two years, and much of making Indelible has been a response to and a conversation with these big problems. Through the book events, and before that, through planning these events—especially the ones in cities I couldn’t go to myself, where local writers stepped up to celebrate the anthology and what it stands for—I got to feel the true power, and grassroots power, of this movement in this moment in time.

Relatedly, sort of, you’ve both heard me talk about why making Indelible a multi-genre anthology felt important to me from the start. In short: I believe that it’s our responsibility as a society in times of crisis to encourage and receive art in all the forms it takes, and I believe multi-genre is a form of inclusivity we should strive toward. I’m always curious to hear other writers’ thoughts on this issue.

DS: I love that this book is multi-genre because that in itself is a political statement. The feminist movement today, or dare I say one goal of the whole Left today, is to dismantle boundaries—to embrace gender fluidity and racial equality, to open borders. Categorizing a book as one genre or another used to be a dogmatic practice, but ultimately who does that serve (other than people shelving books at bookstores)? I’m not suggesting that it’s okay for a writer to say, “Here’s my true book about surviving a genocide,” if she did not in fact survive a genocide, but I do love writing that might be poetry or might be creative nonfiction or might be a lyric something-or-other. I love that Indelible is an anthology of woman-identifying and non-binary writers writing whatever the hell they want to write. It’s an example of structure reflecting theme.

MJS: Yes. I was so excited to learn that this would be a multi-genre anthology. I think unsettling genre is crucial for literary conversations about power. You know, I nerd out on languages, and I talk with students about this all the time—how in Spanish and French (and, I imagine, other Romance languages), “gender” and “genre” have the same pronunciation and spelling. In French, “Genre” is a polyseme that takes on both meanings. (It also means “type” or “kind”). In Spanish it’s “género.” On one hand, I think that speaks to the Western impulse to divide and categorize, as Diana points out—and how that impacts all of our discussions of gender in ways we may not acknowledge or even see. But, as writers, I think paying attention to literary genre also allows us to undo those categories, and break down the boundaries, as you’ve both said. And when we mess with genre in discussions of gender and/or race, class, ability, embodiment, sexuality, nation, and more, I think we have the chance to pierce those structures as well.

DS: Shelly and I nerd out a lot on language together, too, Mecca! We both speak (and often live in) our second languages, and making comparisons between English and other languages, not to mention between American culture and other cultures, is endlessly fascinating. Comparison is like a black light, illuminating issues of power and privilege that are otherwise hard to see.

And like you said, that impulse to categorize (and organize?) is particularly Western. It’s a method of control, one that art, ideally, acknowledges and messes with or ignores completely.

When I first moved to Mexico, I couldn’t stop noticing how much the dogs were barking. No one was shushing them. Noise regulations in Mexico aren’t enforced the way they are in the States, but beyond that: in Mexico, there’s a respect for nature that struck me as novel. Dogs are allowed to be dogs. I love that. That’s what I want from art. Let it bark all night if it needs to. Let it be what it needs to be.

MJS: I find myself thinking and talking a lot about my students in this conversation we’re having. I wonder what your experiences have been talking about #MeToo with generations other than your/our own.

SO: I love this question, Mecca. I was hyper aware of age in curating the book; it felt crucial to also invite writers who were dealing with this bullshit before I was born, whose perspective was much broader than mine could ever be.

Something that brought me to tears while I was touring with the book was seeing mothers and daughters at our events. It happened often, and it wrecked me. Or even just a young woman asking me to sign the book for her mother, or the other way around, which also happened quite a bit. I felt a very specific kind of pain around these interaction every time—the realization of how this societal illness of ours connects generations of women—alongside a careful, gentle hope that maybe we are beginning to heal.

DS: I like that you’re thinking about age as a determining factor, Mecca. The younger generation seems smart and open and I’m so relieved. I see Greta Thunberg and Malala and Emma González and I think…maybe we’ll be okay?

I guess I find myself thinking less about generational responses to feminism than about how the conversations vary from country to country. In many parts of Latin America, for instance, feminism is exploding. But the strength of the resistance to it is quite powerful, too. Femicide statistics have risen in the wake of the #NiUnaMenos hashtag—a movement to call attention to Latin America’s alarming rates of femicide—so some draw the sloppy conclusion that activism doesn’t work, that feminism is bad for women. Some further conclude that feminists are hypocrites because if feminists hated murder so much, they wouldn’t fight to legalize abortion. And on and on. I don’t mean to single out Latin America, but it’s an interesting microcosm of resistance-to-resistance. I try to trust that things have to get worse before they get better. I also try to trust that the death rattle of harmful and antiquated ideas, institutions, and practices is loud and grotesque.

SO: Indelible features a significant array of voices and backgrounds; this felt not just crucial, as it always does, but urgent, since at the time we were hearing predominantly from white, straight, beautiful actresses. How do you feel about the inclusivity of the #MeToo conversation in 2019? And would you say we’ve successfully shifted the cultural perception that appearance affects whether or not a woman gets harassed or abused?

DS: I don’t take kindly to the implication that I’m not a “beautiful actress.” Jeez.

MJS: I am definitely a beautiful actress.

DS: I peeked at your website. You are!

SO: I apologize and take full responsibility for not realizing you were both beautiful actresses. Someone else ask a question, then.

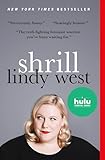

DS: I’ve seen a lot of cool art in recent years that challenges the notion that the gift of shitty male behavior is bestowed only on certain types of women. A couple off the top of my head are Shrill (both Lindy West’s book and the Hulu series based on it) and Orange Is the New Black. But no, I don’t think we have successfully shifted the cultural perception yet. In June, the president of the United States rejected a sexual assault allegation against him by arguing that she wasn’t his “type.”

DS: I’ve seen a lot of cool art in recent years that challenges the notion that the gift of shitty male behavior is bestowed only on certain types of women. A couple off the top of my head are Shrill (both Lindy West’s book and the Hulu series based on it) and Orange Is the New Black. But no, I don’t think we have successfully shifted the cultural perception yet. In June, the president of the United States rejected a sexual assault allegation against him by arguing that she wasn’t his “type.”

MJS: I agree that that perception has not shifted. I think writing by Ntozake Shange, Toni Morrison, Gloria Anzaldúa, Janet Mock, June Jordan, Dionne Brand, Jamaica Kincaid, Lenelle Moïse, Suzan-Lori Parks, Cherrie Moraga, Carmen Maria Machado, Nina Sharma, Roxanne Shanté, Roxane Gay, Queen Latifah, Sapphire, Reina Gossett, Bushra Rehman, Aishah Shahidah Simmons, Darnell L. Moore, and many others has been doing that work.

The post The State of #MeToo appeared first on The Millions.

Source : The State of #MeToo