I recently read Shadow Life, a new graphic novel by Hiromi Goto and Ann Xu. It’s a stunning book that I’ve been loudly recommending to everyone in my life, and one I can’t stop thinking about. The heroine, Kumiko, is a trash-talking, gives-no-fucks, absolutely no-nonsense, bitingly funny 76-year-old bisexual woman. She is my new favorite elderly lady in fiction, and I will fight anyone who tries to hurt her (even though she is eminently capable, and spends a whole book fighting for herself).

The story opens just after Kumiko busts out of the assisted living facility her adult daughters moved her into. She’s not happy there, so she finds an apartment in the city, and sets up a sweet little life for herself. It’s full of simple pleasures: swimming laps at the pool, brewing the perfect cup of tea, eating what she pleases. She lets her daughters know she’s safe, but refuses to tell them where she is, steadfastly ignoring their increasingly shrill calls and emails. She knows what she wants, and she defends it fiercely, her daughters and the rest of the world be damned.

But the peace of her new life is shattered when Death’s shadow comes calling for her. Kumiko has no intention of going along quietly, so she does what any badass old lady would do: calmly traps Death’s shadow in a vacuum cleaner, and goes about her day. Of course, it’s not that simple. The rest of the book follows her many delightful and often hilarious adventures as she works to fend off Death for good, or at least until she’s ready. It takes all of her considerable creativity, along the help of several new friends and her ex — another complicated and beautifully drawn elderly woman.

I read this book in an afternoon and knew immediately it would become one of my favorite graphic novels. But I wasn’t prepared for how often I found myself thinking about it. I finished it back in April, and now I find Kumiko pops into my thoughts all time: while I’m washing dishes, folding laundry, walking my dog. Specifically, the tenderness with which Xu drew Kumiko’s aging body is forever lodged in my heart.

These drawings took my breath away. Xu takes so much care to draw Kumiko as she is. She captures her many wrinkles, the folds of her skin, the tiredness behind her eyes. Much of the book concerns the small moments that make up Kumiko’s ordinary life. We see her slowly walking to the store to buy groceries, carefully steeping her tea, easing herself down on her mat to sleep. We also see her naked, or partially naked, a lot: in the shower, changing her clothes, swimming laps and soaking in the hot tub at the neighborhood pool. There is so much vulnerability and honesty in all of these scenes. It almost felt too real, like I was seeing a part of Kumiko that didn’t belong to me. But I didn’t want to look away from it, either.

Xu’s drawings celebrate Kumiko’s age and life experiences. She carries her body with the ease of long familiarity, an ease that Xu somehow translates onto the page in laugh lines and curves and belly fat. There’s one illustration where Kumiko is laughing to herself, exasperated by something her daughter wrote in an email, that made me catch my breath. I was not prepared for the powerful magic of this simple moment: an old queer lady, sitting alone at her kitchen table and laughing gleefully, her face wide open with mirth.

Xu also captures the inevitable truths of living in an aging body, and those moments are just as moving. She draws Kumiko’s aching feet, the care she takes to pull herself out of the pool, the creases of pain around her eyes. All of these complexities and contradictions, these little details of joy and heartbreak, are etched into Kumiko’s face and 76-year-old body. It’s not glamorous; it’s just true. This is what I can’t get out of my head.

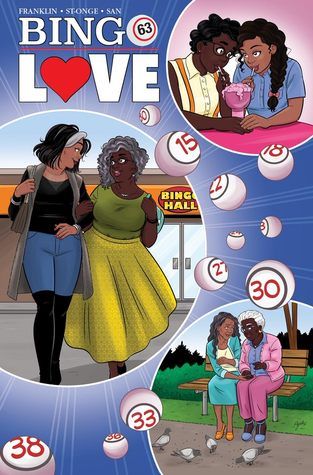

How often do we get to see queer elders, especially queer elders of color, drawn like this on the page? I remember this is what I loved most about Tee Franklin’s graphic novel, Bingo Love. It’s a story about two Black women in their 60s, high school lovers who find each other and fall in love again after decades apart. I read it 2018, but I can still see the drawings of Hazel and Mari so clearly. Watching these older women fall in love, and especially getting to see the physicality of their relationship — not just the sex scenes, but the two of them holding hands, laughing with each other on the couch, sharing a meal — gave me the same sense of joyful possibility that Shadow Life did.

Similarly, the queer grandmothers in the charming graphic novel Mooncakes by Suzanne Walker and Wendy Xu absolutely stole the show for me. The story focuses on their granddaughter Nova, so the grandmothers aren’t drawn in the same kind of intimate detail that Kumiko is. But from the moment they first appeared, in swishy skirts and baggy sweaters, grey-haired and laugh-lined, in their magical bookshop, I felt that same rush of familiarity, that same pull on my heart. Seeing them was like looking into my own future — or a possible future that I desperately wanted.

There aren’t a lot of queer elders in fiction to begin with. That’s part of what makes seeing them drawn so truthfully in graphic novels such a powerful, transporting experience. There’s a lot of talk about books as mirrors and windows, about the power of seeing yourself reflected in a story, and of reading stories about experiences different from your own. But how often do we talk about books as portals? What about the power of seeing a possible version of yourself, not as you are, but as you could be?

The reason I can’t get Kumiko out of my head isn’t because her story is a mirror or a window, although, in different ways, for me, it’s both. Her story, and the stories of the queer elders in these graphic novels, is possibility. Seeing her old body celebrated and honored allows me to imagine my own old body. Seeing queer elders come alive on the page, imperfect and full of regret, still struggling, still afraid of death, still falling in love, dealing with pills and back pain and a world that wants to kill or erase them, watching these funny, weird, loving, messy elders have sex and fight monsters and bask in the luxurious pleasure of a cup of tea — it creates a portal into a queer future, and gives me space to imagine myself there.

Source : The Power of Portals: Seeing My Own Future in Graphic Novels About Queer Elders