It was the era of Waldenbooks, Crown Books, Bookland, and the early start of Borders. It was the era of You Can’t Do That On Television and Clarissa explaining it all. Grunge bands ruled the airwaves, the OJ Simpson car chase was the biggest thing live news had ever seen, and the first web browser went online.

While all this was happening, four girls in Stoneybrook, Connecticut, were plotting how to take their little babysitting business, run from Claudia Kishi’s bedroom, and turn it into a global empire.

The Baby-Sitters Club (BSC), founded by a rag tag team of four 7th-grade girls — Kristy, Mary Anne, Claudia, and Stacey — would take on everything from babies to dogs, snowstorms to shipwrecks, divorce, death, and any and everything in between.

Over time, the BSC grew to ten members and the series to 213 books, which have sold more than 176 million copies worldwide. What began as a humble idea in the late 1980s and early 1990s exploded into a phenomenon like none other.

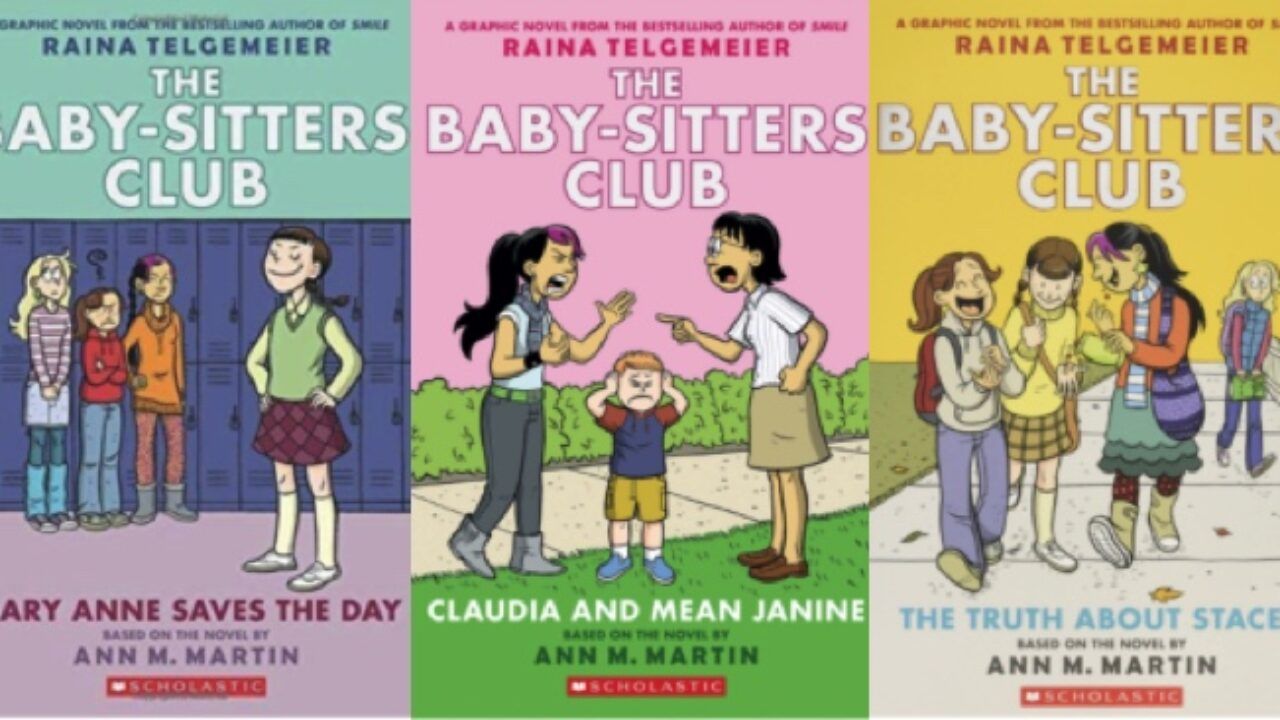

The Baby-Sitters Club entered the world in 1986. In the decades since, it has spun off into side-series, graphic novel series, a standalone film, a TV series, board games, as well as contemporary audiobooks and a Netflix series.

Why is it readers love this series so much? What gives the Baby-Sitters Club series staying power unlike any other for young readers? Why does this fandom thrive, and how does it remain a welcoming, inclusive community?

David Levithan, an award-winning young adult author, as well as publisher and editorial director at Scholastic, began his career at the peak of Baby-Sitters Club popularity.

“I started off as an intern here when I was 19 and, by shear luck, was assigned to, among other people, Bethany Buck, who was then the editor of The Baby-Sitter’s Club. I had never heard of The Baby-Sitter’s Club. […] I found many of my friends had younger siblings who were devoted, devoted fans and I, therefore, had the coolest job in the universe, according to them,” he said.

By the time Levitan joined Scholastic, there were already more than 50 books in the series, and there was no end in sight.

“I started with it already being a hit to a degree that it really was almost unprecedented. And I think that it was just sort of astonishing to see. Usually a series ran for 10 or 12 books, if it was lucky, with the exception of something like The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, most series had a nice life and then they ended.”

But The Baby-Sitters Club was just getting started.

“And there were all the spin offs and there were such devoted fans that it really was a question of how many stories can we tell?”

Before we get too far down that road, let’s go back to book one.

The Baby-Sitters Club begins with Kristy’s Great Idea. Kristy’s single mother, who usually relies on Kristy, her older brother, and a rotation of sitters, is desperate to find someone to watch Kristy’s younger siblings. When she’s unable to find a sitter one day, Kristy has an idea: what if people seeking a babysitter could call one number at a specific time and date each week and reach a number of potential sitters at once?

She presents the idea to best friend and neighbor Mary Anne, who loves it, then they bring in Claudia Kishi, who suggests inviting Stacey McGill. And thus, the Babysitters Club is born.

The series was initially planned to be just four books, but Scholastic quickly recognized they had a hit on their hands and ordered more. As the shelves of Baby-Sitters Club books filled up, the club itself was also growing. By the end of the series, the BSC boasted ten members. Clearly, something very special was happening.

“The whole premise, the whole idea of the Baby-Sitter’s Club was so ahead of its time, in a way. Because it’s these young women coming into their own, but they’re entrepreneurs and they’re strong and they’re finding work for themselves. And it’s a we can do it attitude. So it was pretty cool at that time of being 11, 11, 12, to be exposed to that positive role model,” said Schulyer Fisk, who played Kristy in the 1995 The Baby-Sitters Club film.

“I really loved that Kristy was the leader. I loved that she was a tomboy and she was strong and she was really a go getter. During the movie, we have a summer camp,” explains Fisk. “And she’s leading the kids with a bullhorn and telling people where to go and organizing it. And it’s a lot of work and she just, she has no fear. And I thought that that was really cool. And she was friends with the guys, which I liked. I just thought she was a cool girl and I thought her confidence was really something special.”

It’s empowering to see confident, can-do, go-getter girls and women in books and on screen at any stage of life, but the BSC reached its audience at a particularly important time.

“Because that age, middle school age is so hard. And kids can be so mean and so tough and even your closest friends can be horrible to you. So to be able to tap into someone with an inner strength like that was really, it was beneficial for my own personal life,” said Fisk.

And it’s not just the characters’ outward behavior that was inspiring. The girls had rich personal lives, and they were diverse in a way that was rare to see at the time.

Kristy came from a family of divorce that saw a remarriage and blended family; Mary Anne was raised by a protective single father after her mother’s death; Stacey had diabetes and was nervous to tell her new friends about it; Dawn moved from California with her mother after her parents divorced.

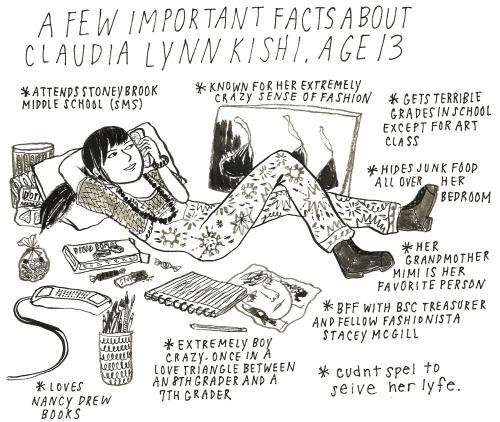

And more, Stoneybrook featured characters like Claudia Kishi, a Japanese American girl who was a superbly fashionable artist living with a high-achieving sister, a beloved grandmother, and married parents.

For award-winning comic artist and author Yumi Sakugawa, Claudia offered an opportunity to see herself on the page.

“I love Claudia Kishi not just because she is Asian-American and Japanese-American, like me. The other thing that resonated so much with me is that she is an artist like me. Growing up, there were hardly any Asian-American characters, Asian-American girl characters, and so to find one Asian-American character who was Japanese-American, a girl, a creative person, that was just like finding a unicorn. I felt like I probably came across her when I was 8 or 9 years old, and so to have this cool 13-year-old girl, who was artsy, and considered cool, and popular, and well-loved, and well-respected by her peers, I think that was just this narrative for me that I just didn’t find anywhere else,” said Sakugawa.

Eugene Myers, an award-winning YA science fiction author, agrees.

“Claudia, I think…She didn’t stand out just because she was Asian, but she stood out because she was very different. She made a point of having her own style, and the thing I maybe remember about her more than her being Asian is she was an artist. She was also on the cover of some of the books. How many Asians were on the covers of children’s books? Like, ever?”

Even today, that’s much less common than it should be. That Claudia was visible at all was a big deal, but it’s how she showed up that really made an impact.

“She was not ashamed of being her own person because I think that, as somebody growing up, who, as an Asian living among mostly other white people, you try to fit in,” said Myers. “You’re already drawing attention because you look different from everyone else, but she was owning it, and being different for other reasons, so that’s not necessarily the first thing someone would even necessarily notice, is “Oh, she’s Asian.” It was like, “Oh, no, she’s got this really cool outfit.” Or, “Look at her earrings.””

—

Stoneybrook — and the Baby-Sitters Club — was also home to dancer Jessi Ramsey and her family, who were among the few Black people in town. Remarkably, the books addressed the racism and hostility the Ramseys experienced head-on.

Amma Marfo, an independent higher education professional, writer, and editor, grew up with the series and found herself identifying with different girls at different times

“I think of the original four, I was probably closest to Claudia. And then as other people started coming in and out, there were parts of me that really liked Dawn. There are parts that felt a lot like a Mallory. Once Jessi came along, there were some similarities there as well,” she said. “I think there are a lot of things to be said about finding somebody that looks like you in a book. And at that point, there really weren’t that many, especially talking about some of the other reading that I’d been doing. It was really, really white and I lived in an area that was really, really white. So that was very much my reality.”

Then Jessi showed up, and Amma found a deeper connection to the series.

“It was the same circumstances. It was somebody who has right around school going age, took ballet. I was also taking ballet. Who had a younger sibling that was premature, same. So there were a lot of parallels that came from pretty deep within the literature and how the character was introduced.”

It was amazing for Amma to be able to see herself in Jessi. But when other people started identifying her with the character, things got more complicated.

“There’s a difference between identifying yourself as a character and somebody else identifying you as a character,” said Marfo. “And for me, anytime I was identified as a Jessi, it felt purely cosmetic, purely appearance ridden just like you’re the black character and there’s black character, ergo that’s you.”

“So it felt like more quickly arrived at less nuanced idea of who are you most like? It’s like well I see you look like this person and therefore that’s who you are. And that was really different from how I came to identify as that character,” she added.

As David Levithan said earlier, most series have a nice life, and then they end. If they’re lucky enough to be beloved, they live on their fans’ nostalgia-fueled memories.

And it takes more than nostalgia to give a series staying power for generations of readers. In the Baby-Sitters Club, there’s something more than a cast of archetypal characters that keeps it relevant and powerful.

For Yumi, the series is a portal to a time and space that was real and honest, without being cloying or too much like an after school special — it didn’t suffer from the one-dimensionality that so-called “issue books” or “problem novels” from the same time frame did.

“It’s just this great, safe space, where you got to explore through these characters what it means to be both a kid, and also a responsible person who takes care of other people’s kids. Every book just has such a nuanced lesson on dealing with toxic friends, or dealing with friends who change in ways that make you uncomfortable, or dealing with heartbreak and boys, or teachers who don’t like you. I feel like because they sort of gave themselves permission to be frozen in time, and to go through every iteration of what a middle schooler would go through, they then created this whole library of young adult experiences that an eight to twelve year old girl can explore safely, in the comfort of these very predictable and reliable characters,” she said.

“It was this comforting worldview that no matter what, you have friends you could rely on. If you’re a good person, you will be rewarded.”

Levithan agrees, adding that the entire building of Stoneybrook as a world, made a space for readers to not just escape, but to really belong.

“We usually talk about worldbuilding in terms of science fiction universes and fantasy universes. But, Stoneybrook was as much of an exercise in world building as any other literary adventure. And I think that what was so amazing for readers is that they could, for the two or three hours it took to read the book, they could live there and they got to know the people, they got to the know the babysitters, the babysitting charges, the families. So, you would just escape into that world and it wasn’t a fantasy world. It wasn’t a Sweet Valley High world where people weren’t really like you, they were like the fantasy version of popular people. Instead, it was like a lot of people like you that were articulating a lot of things that you didn’t necessarily know how to articulate yet,” he explained.

That sense of connection and belonging turned BSC readers into devoted fans. The series nurtured this relationship over 213 books that all stayed true to the world of Stoneybrook, allowing readers to stay true to it as well.

And the fact that the girls were young entrepreneurs? That didn’t hurt, either. Amma credits being exposed to young girls taking charge and building their own company as inspiration for her career.

“So I remember around 4th or 5th grade, I got really into making bows and packaging decorations out of wrapping paper and I wanted to sell them in the neighborhood. So I wrote this business plan, typed it up, presented it to my dad, and asked for him to invest in it. I remember that direct connection from kids starting a business, [and] I could start a business. And then later on women starting businesses, I could do that for myself. So absolutely, it’s linked in a couple of different ways.”

Here, again, the sheer volume of books in the series plays a key role. It wasn’t just one story about girls running a business, it was hundreds of them.

Schuyler Fisk adds that seeing such a template of friendship made — and continues to make — a huge impression.

“I think it’s just a special thing that Ann M. Martin created and that people connect with. When you boil it down, it’s about friendships and confidence and all these things that we all struggle with, not just when we’re young but our whole lives. And relationships and things that are going on with your family and work balance and trying to get ahead,” said Fisk. “Those never get old, those never go out of style.”

She adds, “I really like the sisterhood that the girls have, the friendship. Sometimes girls struggle with girl-girl friendships because there’s a competition. Oh, is she prettier than me? Is she better than me? She’s smarter than me and better at sports.”

Schuyler would know — 20 years on, she remains friends with the women who played her fellow babysitters in the original movie.

Thirty-five years and 176 million copies later, The Baby-Sitters Club remains part of contemporary culture and has a loyal, welcoming, and enduring fandom. It started early, growing up alongside the internet itself. Early fan-sites like “What Claudia Wore” and LiveJournal communities emerged prior to social media, but as technology and, indeed, social media expanded, so did the possibilities for sharing love, sharing art, and sharing passion for the series.

Jack Shepherd and Tanner Greer are the cohosts of the podcast The Baby-Sitters Club Club. The show, which chronicles two men in their 30s reading and discussing the series, grew out of Jack’s passion for the books, which started when he was young.

“My history with The Baby-Sitters Club is that when I moved to the U.S. from England, I think I was probably 7 or 8 years old. My best and only friend was my cousin and so I spent a lot of time hanging out at her house and she just had this entire library of BSC books and Sweet Valley High. And so I just ended up sitting in her room and reading the books.”

“There’s something unique about these books that is, it’s like it’s all girls and it’s girls working together and being entrepreneurial and there’s something that’s fun and cool about that and it’s kind of the opposite of Sweet Valley High, which is like girls fighting with each other over boys,” he said. “And the Baby-Sitters Club, it seemed like, chose to do the opposite of that. I think that is a big part of what the lasting value is. I do think, reading them again with fresh eyes, I’m impressed.’

Like any media, the BSC books are a product of their time, but it’s clear, even reading them through today’s lens, that a lot of care and energy went into presenting diverse characters and perspectives.

And it’s especially compelling when taken alongside another popular series of the day, Sweet Valley High.

“We just read a book, Sweet Valley High super special, to guest on a podcast called Sweet Valley Diaries and there’s one character and she is deaf and the way they deal with her deafness in Sweet Valley High, is that they send her to the most expensive surgeon in the world and cure her.”

He continued, “And in Baby-Sitters Club, they just have a deaf character called Matt Braddock and he’s deaf and everybody has to learn ASL. I think that contrast really brings out the genuine effort that was made throughout these books to make them interesting and make them real and make them true to different people’s perspectives. And I think that that has been really fun.”

Although they didn’t predict the popularity of their podcast, Jack says he and Tanner aren’t entirely surprised, either. The BSC has a loyal fanbase and, from what Jack himself experienced in early online fandom, he knew the series was deeply loved.

“I mean the classic all time great Baby-Sitters Club fan based creation is the blog, What Claudia Wore. It goes through each book and talks about what Claudia wore that week, which could be an entire podcast of itself, I’m realizing.”

“And there’s a series of stuff that’s called, I think BSC Snark that was like LiveJournal culture,” he said. “There were these cool artifacts from a different internet, that was probably 2005 onward, where people kind of in a way that is similar to what we were trying to do with the podcast, revisited these books as adults. And picked out what was fun about it and what was silly about it.”

The BSC’s first wave of fans came of age before blogs, online communities, and social media were a thing…so when they did eventually go online and find each other, they had 20 years’ worth of nostalgia to pour into fandom.

“It is so much fun to literally, 20 or 30 years later, share experiences of these things that, at the time, I’d talked to my cousin about it and that was it. And I certainly didn’t talk to the boys at school about it. That’s a really fun thing about any nostalgic property. But especially something that, it has to have this lasting value, which I think the BSC really does.”

—

Fan projects about the series often have legs, as Yumi saw when she created her fanzine “Claudia Kishi, My Asian American Female Role Model.” What started as a feature for one site connected her to a wealth of fellow Claudia and Baby-Sitters Club fans worldwide.

“I made my comic in my late 20s because I was noticing around that time that my contemporaries who grew up reading The Baby-Sitters Club, were starting to write their own nostalgia blog pieces and essays. It was exciting for me to see my peers touch upon a book series that was very near and dear to my heart. What I really wanted was for somebody to acknowledge how cool Claudia was, but from this Asian-American perspective.”

Yumi’s first big break came when she shared a link to her comic on Angry Asian Man, a popular pop culture blog at the time, and the creator Phil Yu tweeted and shared it to his large following.

“I just got such an overwhelming response from many Asian-American women who were just like, ‘Oh my god, yeah. I totally feel what you’re feeling. Claudia Kishi was this one Asian-American girl character I had growing up.’ It just elicited such a personal, intimate response that just reminded me so much of how empowering, and personal, and intimate it is to see yourself, to see somebody who looks like you reflected in books, and TV, and movies.”

While the fandoms of some franchises meet new iterations of their beloved series with skepticism and even backlash, Amma believes that for the BSC, the new takes help the originals endure. Fans both new and seasoned greet them with openness and enthusiasm.

“I wonder if some of it too is associated with who we were in a lot of ways when that source material came out and how it existed. So the idea of it feeling really communal and like it’s something that people again can engage with for the most part civilly. That’s who we were when we first got to it. And I think in some ways it brings us back,” she said.

That’s an important and powerful distinction when many fandoms seem to thrive on one-upmanship and the currency of trivia, rather than community and connection.

“But that’s not who we were when we read these books. And I think that being able to engage with it again in that wholesome way might be indicative of maybe some things that are missing other places, or that other fandoms maybe don’t necessarily encourage or have core to their being.”

Naia Cucukov, the executive producer on the Netflix adaptation of the series, also notes that it’s a series that spans generations now, as those who grew up with the babysitters now have the chance to share these stories with their children. In an era where there’s so much fractured enjoyment of entertainment — everyone can stream from their own personal devices — stories like the BSC allow for a powerful bonding experience.

“We, over at Walden [Media], are always looking for these kind of co-viewing moments. There are so few and far between now, but there’s some things that are special about characters that you loved as a child and really helped shape your own personal identity, and being able to share that with your kids, to me that’s a really special thing,” she said.

The legacy of the BSC is, of course, also the legacy of creator and author Ann M. Martin. Though she did not write the entire series, she’s credited with writing the first 35 books in the original series and has had a hand in the creation of each and every book since.

Shannon Supple is the lead steward of the Mortimer Rare Book Collection, part of Smith College Special Collections. The Mortimer collection is home to the Ann M. Martin papers — Martin is an alumna of Smith College — which were donated to the school 2013.

The Ann M. Martin papers include synopses, outlines, drafts, proposals, and myriad other material related to her work on the Babysitters Club.

“These materials are so wonderful because they illuminate her writing and creative process over time. You can dig into her creative process around a very specific edition of a particular Baby-Sitter’s Club book, or you can look sort of across at how did things change and how did her process shift and change from The Baby-Sitter’s Club series to the Little Sister series, to Main Street, to some of the later work that she’s been working on.”

What strikes Supple about the papers — and indeed, what resonates with readers — is how much work Martin put into crafting books that featured not just well-rounded characters, but also into doing the research to ensure that issues raised in the books were presented with sensitivity and honesty for young readers.

“You can see that she would actually go into scholarly journals. She would go into newspaper articles, and read up on that particular area so she would be able to create depth and speak from a place of knowledge around some of these hard issues,” she said.

Perhaps one of the big reasons why so many readers have such fondness for the series and continue to think about how much it has inspired them and continues to inspire them comes from the way Martin constructed the books. Where characters matter and where plot matters, Supple says something else stands out.

“Her synopsis include how she expects the story to invoke feeling in the reader at particular points. In the synopsis, she’ll say her goal is for the readers to have positive feelings toward a particular character or group. So, she’s not necessarily even at that stage building a character or the plot, she’s saying, “My goal through chapter two is that the reader will feel connected and like these particular characters or this particular circumstance.””

And that’s what marks Martin as a master of her craft — she’s never just planning what happens to whom. She is always thinking about how it will make readers feel, and what it will do for them.

Cucukov agrees — and believes that this blueprint Martin made in the initial series is precisely why it remains relevant and viable in today’s pop culture landscape. Bringing the girls into today’s era for the new show, she says, really only meant thinking about the big challenges they’d be facing now and that, when originally published, weren’t necessarily in the cultural zeitgeist.

“It’s dealing with issues that kids today are dealing with, taking things like the worst parents that step further, talking about same-sex couples, talking about just the things that are just a given in our modern world that I think back then weren’t at all in the popular conversation,” said Cucukov. “At the same time, we are trying to make a more kind of inclusive landscape for our girls. So Stoneybrook is going to feel a little bit more like modern times. I think that it’s going to feel like a very diverse, really fully fleshed out place, and then that’s going to include some of our girls as well.”

And as so much of life in modern times is influenced by technology, the girls of the BSC have unique relationships to it and experiences with it.

“Someone like Stacey was cyber-bullied at her last school, and that’s part of the reason why she’s moved to Stoneybrook. Someone like a Claudia, who’s got a sister who’s a tech genius, probably is a little bit more of a Luddite and just really doesn’t like modern technology. And that’s a whole wave of kids today as well, the ones that are going back to flip phones and stuff,” said Naia. “So, we’re playing with all of those things, at the same time, trying to keep it as timeless as possible because at the end of the day, your friendships with your girlfriends, your relationships with your parents, your first crushes, all of those things are so universal and have been issues for young girls and will continue to be issues for young girls for all time.”

—

Today, it’s not just nostalgic readers of a certain age who feel connected the BSC. It’s young readers, too. New formats invite new readerships, who are brought into the multigenerational fold of lifetime fans.

“I continue to be surprised at what a deep impact that movie has made and continues to make to people, to the new generation of kids that are watching it. But also the people that are in their thirties and that grew up with it,” said Fisk. “There’s something in its simplicity that’s really connected with a lot of people and continues to. And I don’t think I even realized that in the beginning when I started reading the books and when I made the movie. But I think that as I’ve gotten older and looking back, to see how it’s grown and how that our fans of the movie grow with us and continue to, and the new generations become hip to it. Now they’re doing new projects like this Netflix series. It’s so exciting for all of us.”

Shannon agrees.

“One of the fun moments I had in one of my few weeks on the job at Smith was a girl who was about 8 or 9 years old, maybe a little older, maybe 10, walked into the library with her mom and sort of asked shyly if we had some special information about The Baby-Sitter’s Club. She was kind of looking down at her feet, but her mom was encouraging her to ask the questions that she wanted. It was so fun, because her mom clearly had known her interests and brought her to the right place to learn more about what we had.”

“I was just delighted, because she was so excited to see things like outlines and book covers. I thought, “Is this 10-, 9-year-old going to be interested in these materials?” But it was special for her, and it was special to see Ann’s handwriting and sort the work of developing a book that has a lot of meaning to her. I thought that was so much fun.”

That was just a few years ago, and with the Netflix series, Supple anticipates even more continued interest in the BSC.

The world of Stoneybrook is vast and rich, offering readers many points of entry and plenty space to bring their own perspectives and ideas. Yumi believes that this is a key reason the stories resonate with readers and will continue to find new fans, both young and old.

“It’s just this interesting portal where everyone’s eternally 13, and they go through all the seasons multiple times. And it’s just this great, safe space, where you got to explore through these characters what it means to be both a kid, and also a responsible person who takes care of other people’s kids,” said Yumi. “To go through every iteration of what a middle schooler would go through, I felt like they then created this whole library of young adult experiences that an 8- to 12-year-old can explore safely, in the comfort of these very predictable and reliable characters.’

The notability can’t be overstated. David Levithan agrees, adding that we haven’t yet seen another realistic series with the staying power of the BSC.

“One of the things we talk about now is could it happen again? Was it because of the market being what it was at that time in the ’80s, that’s something that is so much about reality could go for so many books and could create a world like that,” he said. “But, for an everyday series, I don’t think there has been anything like it. I think it really is unique.”

And more, says Eugene, it’s possible we won’t see something like this again because the premise of the stories couldn’t be replicated today.

“If you were to try to make a truly contemporary version of The Baby-Sitters Club, it wouldn’t work. Today, we’ve got Care.com and websites, and everybody has to be vetted. You have to have all these references. When I’m looking for a babysitter, I’m like, “Do you know CPR? Do you know first aid?” You try to meet people, so you know that they’re not going to hurt your child. There’s all these scary stories about babysitters. And, just the idea of teenage girls going to strangers’ houses. Some of those elements in today’s society really seem strange.”

He continued. “And so, I think that possibly some of the modern-day appeal for it is not even a nostalgia because kids wouldn’t remember this, but just a simpler time. There’s an innocence to it all that, I think, you can find appealing.”

It’s about more than nostalgia. It’s about more than yearning for a simpler time. It’s about an innocence and a universal connection to characters who experience the same kinds of real-life things that young people do. Cucukov agrees, referencing a phrase Jack and Tanner use on The Baby-Sitters Club Club podcast and suggesting that, similar to classics like Little Women, The Baby-Sitters Club allows for each generation to connect, to share, and to make these stories their own.

“It’s like it’s almost universal, but at the same time it’s so deeply personal. Everyone has their own kind of relation to this series, and that’s what’s really cool about it,” said Cucukov. “The girls will always and forever, to borrow a phrase from The Baby-Sitters Club Club, be encased in amber at the age of 13. This is a series about being accepting and tolerant of all. It’s just about being a good person.”

“There’s something about like the things that you loved as a kid that put you into a really kind of vulnerable, happy place,” she concluded.

The above piece comes from our former Annotated podcast series, originally aired in September 2019. If you liked this, enjoy the companion piece about The Baby-Sitters Club’s legacy.

Source : The Legacy of The Baby-Sitters Club