This is a guest post from Camille A. Collins. Camille has an MFA in Creative Writing from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has been the recipient of the Short Fiction Prize from the South Carolina Arts Commission, and her writing has appeared in The Twisted Vine, a literary journal of Western New Mexico University. Her novel THE EXENE CHRONICLES is out with Brain Mill Press. She likes writing about music, and has contributed features and reviews to Afropunk and BUST. She lives in New York City. You can find her on Twitter at @ponei_rosa9.

Few authors do a better job of passionately articulating the need for diverse characters in YA literature than Jason Reynolds, who once told The Washington Post, “I learned just how…necessary it is sometimes to humanize those who have been vilified.” It’s not that I don’t appreciate the need myself—my debut novel The Exene Chronicles centers on Lia, one of a very small handful of minority students at a high school in a suburb of San Diego, just as I was. But unlike Reynolds, as a kid I think I was pretty resigned to the fact that there weren’t going to be any YA books with characters that looked like me or felt and experienced the same things I did. Not only did I not expect it—I didn’t dare dream it possible. I simply did my best to find common ground in the humanity of characters in books I enjoyed like The Outsiders and Lord of the Flies, unable to imagine a book that might put a black girl at the center of the narrative.

What if there had been some fantastic lore of a band of renegade black girl detectives in motorcycle jackets or pink windbreakers a la The Pink Ladies, solving tricky neighborhood mysteries and taking down bullies on the block? What might it have meant for me as a kid to have such a book? Minority narratives are often expected to reflect pain and deprivation, material, social or otherwise—and they often do, because stuff still goes down. Maybe one day Sasha Obama or Blue Ivy will write a YA book about a kid so privileged they feel disconnected from their community—and just about everybody. At least it would be a fresh take.

I attended a screening of James Spooner’s 2003 film Afro Punk in the fall, for a first-time viewing. It’s from this film that the Afro Punk festival and social platform gets its name. In interview after interview, the black kids in the film say, “well, I was the only black kid in my school…” Time and again, this was the refrain. Who knew that punk, of all things, would offer such a sheltering umbrella for minority youth? With isolation and otherness eventually leading these kids to seek solace and common ground in the formidable battle cry of unadorned lyrics and chaotic beats. It was interesting to learn that as one of the few black kids in Coronado, California, by discovering punk in middle school, I was part of a trend of black misfits in suburban towns across America. Who knew the punk scene would become a de facto after school “chess club” for so many of us? Punk, typically associated with adolescent angst, the frustration of a sanitized suburban idle, a disciplining DIY credo, and temporal oases of rundown ballrooms to thrash out pent up rage, and fear—is usually associated with privilege, and typically that don’t mean black. I hope The Exene Chronicles is a first step towards that different kind of narrative—a new take on the “black experience,” just like the AfroPunk website says.

Thankfully, the future is now and it’s incredible. YA lovers can now choose from a variety of protagonists, from a diverse array of viewpoints and cultures, to both mirror and guide them through cultural and social landscapes familiar and new. The following are a few such books, literary companions—young people of color at the center of their very own narrative. These stories stayed with me, and may offer satisfying accompaniment to you as well.

I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika L. Sanchez

I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter by Erika L. Sanchez

Julia Reyes is a Mexican American teen growing up in Chicago in this unique and addictive novel by Erika L. Sanchez. When her “perfect” older sister Olga suddenly dies, Julia adjusts to her new status of being her parent’s only—and possibly second best—preoccupation. Julia has always been in conflict with her parent’s cultural and social strictures, and in the wake of her sister’s death every argument and bad word she utters seems magnified. Along the way, Julia discovers that maybe Olga, a young adult who stayed on at home and clean houses with her mom, wasn’t so saintly after all. Rich with realistic dialogue and conflict, Sanchez crafts scenarios where the chafing of Mexican cultural tradition against the struggles of a first generation American daughter is nearly tactile. I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter brings a bird’s-eye view into the values and expectations of a working class Mexican American family. Julia is an unabashedly flawed, rebellious character with a heart more tender than she cares to let on—and despite some reviewers complaining that she is “unlikable,” I like her. I get her.

Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend by Erika T. Wurth

Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend by Erika T. Wurth

I can’t believe I’m only just discovering Erika T. Wurth. The journey of 16-year-old Margaritte as told in Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend is haunting and unforgettable. Wurth’s pull-no-punches writing style is a fitting accompaniment to the harsh realities that shape the environment and experiences of this mixed Apache, Chickasaw, Cherokee, and white teen. The numerous indignities Margaritte faces are enough to end anyone. Her home life is fraught with abuse, and the community lousy with drug dealers, users, and pregnant teens with little vision for their future. Intelligent and responsible, with a self-deprecating humor that is damn near heroic given the circumstances, Margaritte hopes to engage with the vices of her Colorado town just enough to beat the system. When she falls in too deep with the wrong guy and finds herself pregnant, her dreams hang in the balance. Wurth is a skilled author who fearlessly depicts an environment so grim it feels almost post-apocalyptic.

Native Americans are no more a monolith than any other group. History was just made when Deb Haaland and Sharice Davids became the first Native American women elected to the U.S. Congress. Still, Margaritte embodies other similar experiences. Her harsh realities mirror that of the four non-Native, West Virginia youth who made national headlines when they became trapped in a mine the other day. They had taken the life-threatening risk while in search for copper wire to sell. Through Margaritte, Wurth draws a fierce, real, and memorable character who allows us to see the kind of town that altogether too many Americans are forced to survive. And although fictional, the novel stands as backstory to help highlight the hellish grid of abuse and codependency that poverty and racism have dealt far too many native youth, and their subsequent vulnerability to crimes such as human trafficking. I cannot shake this story—and I don’t want to.

The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo

The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo

The delicately crafted, emotive National Book Award–winning novel written in verse tells the story of 15-year-old Dominican Harlemite Xiomara. Xiomara’s blossoming is made indelible by Acevedo’s exquisite crafting of content and verse. Marked with the taint of sin for merely existing by her strictly religious Catholic mom, Xiomara is a smoldering volcano of angst and confusion, struggling to adapt to her body and burgeoning womanhood as she crosses the chasm of her mother’s exacting standards and the New York streets, where she’s objectified by catcalls, and falls for a boy named Aman. Xiomara has a twin brother, Xavier, whose obedience stands in contrast to her seemingly constant rebellion. She’s a girl who’s willing to challenge the local priest on sexist biblical narratives, after all. Having been raised in a very religious household myself, I can relate to Xiomara as she begins to take the essential steps needed to claim her identity and liberate herself from someone else’s voice and idea of who she should be. For her part Acevedo, a tricky spider—works stealthily to weave a narrative that closes the divide between poetry and prayer.

A Girl Like That by Tanaz Bhathena

A Girl Like That by Tanaz Bhathena

Who doesn’t love the opportunity reading provides to “travel” and become immersed in unfamiliar worlds? A Girl Like That is a story about two deceased teenagers, told from beyond the grave from multiple perspectives, including that of Zarin and her young Romeo, Porus. In this book, author Tanaz Bhathena brings a deftly woven story that chronicles the life of a rebellious teen girl in modern day Saudi Arabia. The once orphaned Zarin is the subject of ridicule and gossip around her neighborhood and school for her devil-may-care dalliances with boys, and for her beliefs as a Zoroastrian—a religious minority group. Zarin and Porus are killed in a catastrophic car accident in Jeddah. Flashbacks highlight the challenges they endure, from disapproving elders to the scrutiny of the religious police. This is a book to stoke jocular book club discussions. A Girl Like That has received flak in some quarters for the dark characterizations of many of the male Muslim characters, and for the constant in-fighting among the women and girls. A group discussion of how the book may lapse into unfortunate stereotypes is a worthy conversation to have. Still, A Girl Like That offers an intriguing look into the social hierarchies determined by religion, culture (Zarin is of Indian, not Saudi, descent) and familial status in a major, modern Middle Eastern city, comprised of people from an array of regions and religions. Misunderstood Zarin, a social misfit who experiences more than her fair share of hardship in the years leading up to her untimely death, is a character worthy of exploration.

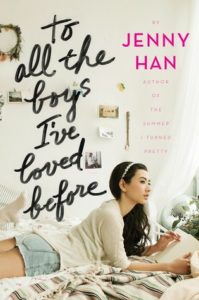

To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han

To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han

Often it is the harshest or most dramatic of minority experiences that satisfies the assumption that life for some communities is all tragedy most of the time. Jenny Han’s novel is a departure from this definition that lands like a breath of fresh air. Lara Jean Covey is one of three “Song girls.” Song is their late Korean mother’s maiden name. The half Asian trio are now on their own with their dad, and with the eldest heading for college, Lara Jean will soon have to assume more responsibilities at home. Perhaps her position as the somewhat sheltered middle daughter is the reason Lara Jean is given to such deeply emotional flights of fancy—her musings are innocently overdramatic when juxtaposed against her naivety. Much of Lara Jean’s love life is lived out through the farewell letters she writes boys when her affections for them have waned. When five such letters are mailed accidentally, the safe next door neighbor Josh and magnetic Peter among the recipients, Lara Jean is cast in an uncomfortable spotlight. Yet, the trouble also fortuitously leads to an alliance, something akin to a milk and cookies version of the pact in Dangerous Liaisons, that affords Lara Jean and Peter a chance to become better acquainted. To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, since adapted into a Netflix movie, is light, romantic teen fare. And sometimes light is just right.

Source : The Future is Now and It’s Inclusive: Young People of Color in YA Books