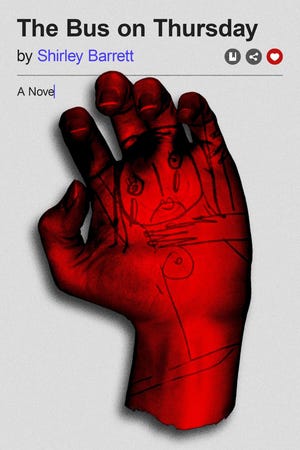

Shirley Barrett on cancer as a demonic infestation

I n the first line of The Bus on Thursday — the latest novel from Australian writer Shirley Barrett — the narrator, Eleanor, discovers a lump in her armpit. Her horror comes true: it’s cancer.

We follow Eleanor as she undergoes surgery, struggles socially and romantically, and, needing a job, moves to the remote town of Talbingo, where she’s hired as an emergency replacement for a beloved schoolteacher who’s mysteriously disappeared. Along the way, she meets a lively cast of humorous and disturbing locals: a friar who declares her to be full of demons, the missing schoolteacher’s suspicious best friend, and a strangely attractive man of seemingly otherworldly virility. The deeper into the story you go, the darker (and funnier) things get.

The novel — which takes the form of Eleanor’s voicey, unpublished blog — is a romp through literary horror, packed with the stunning images that one might expect from a writer who is also a director. But it also gives life to the crushing reality of a cancer patient — the anger, the grief, the crazy-making self-blame. The Bus on Thursday elegantly rides along the edges of these issues.

Shirley Barrett and I corresponded over email about the demonization of cancer, the challenges faced by cancer patients, and the differences between novel-writing and screenwriting.

Joseph Scapellato: The Bus on Thursday is a darkly comedic combination of a cancer patient/survivor story, a small-town transplant drama, a teetering-into-madness tale, and a genre-bending ride right into the heart of horror. And most impressively, it’s often all of these at once! Where this book began for you?

Shirley Barrett: I was interested in the idea that there is a bit of blame attached to getting cancer: you drank too much, you ate processed meats, you wore underwire bras, therefore you brought this upon yourself with your terrible lifestyle choices. And I particularly liked the idea — popular in some evangelical religions -that cancer is a demonic infestation, if you will, and that perhaps you have unwittingly invited this demon in.

The book began as a screenplay, a screenplay which obviously never got made. I’m a filmmaker and I wanted to make a horror film and I had just the location to set it in: Talbingo! Talbingo is a very pretty little town set in the foothills of the Snowy Mountains here in New South Wales, [Australia], and I happen to know it well as my husband’s grandmother lived there. Every Easter, there would be a regular family gathering, so over the years I’ve spent a bit of time there. I’ve always found location to be very important as a stepping-off point in my writing, and there was something about the moody isolation of this place, even amidst its beauty, that seemed to lend itself to horror.

The novel came from the idea that there is a bit of blame attached to getting cancer: you drank too much, you ate processed meats, you wore underwire bras, therefore you brought this upon yourself with your terrible lifestyle choices.

JS: There are so many ways in which this novel is funny. In my reading of it, the humor pours out of the narrator, Eleanor (her voice, her attitude, her ability to consistently make a bad situation worse), her surprising and mysterious encounters with the sharply-drawn supporting characters, and the novel’s playful engagement with horror.

What is your approach to writing comedy? Where do you try to find it, and how do you work to follow it?

SB: The other big part of the book is my friend Kate. She got cancer very young, at age 29, and had a mastectomy which she freely admits totally stuffed up her life. But she was always very funny, in a dark and angry and uproarious kind of way, whenever she’d talk about it, and at one point I taped her talking about it because I was going to write something else on the subject. And so basically, I appropriated my friend’s voice: in fact, the first paragraph of the book is Kate verbatim. And some of the awful things, like the horrible date, happened to her in slightly different form. She is very decent about the whole thing and is keen for Margot Robbie to play her if it ever gets made into a movie.

But in fairness to Kate, who is in reality a lovely and kind person, Eleanor is also very much me at my worst; lazy, impulsive, quick to judge. As for my approach to writing comedy, everything I write turns out more or less comic — I seem incapable of writing anything else. And I realized that this was at odds with it being truly effective as a horror — the comedy cancels out the horror, in my opinion — so for a while I struggled with that but in the end, I threw up my hands and thought, what will be will be.

JS: One of the things that I admire the most about this novel is how it so honestly enacts certain experiences common to cancer patients/survivors. Early in the novel, Eleanor straightforwardly explains a frustrating expectation:

This is the whole problem with having cancer: everyone expects you to have mysteriously acquired some kind of wisdom out of the experience, and if you haven’t, then it’s a personal failing. I mean, people have actually said to me, “Wow, I guess having cancer so young must have given you a whole new perspective on life?” And I always nod and try to look inscrutable, but in fact, if I am completely honest with myself, I have the same old skewed perspective I’ve always had, except now I get to feel guilty about it.

If that weren’t hard enough to deal with, as the novel goes on, multiple characters covertly or overtly suggest that Eleanor’s cancer is her fault — that she has invited it into her body. This idea eventually takes root in her, and resonates with the novel’s other themes in sinister and surprising ways.

What challenges did you face when writing about a cancer patient? What responsibilities (and/or pressures, and/or fears) did you feel and how did you grapple with them?

SB: I did feel a certain anxiety writing about having cancer when I had never been through such a thing, but I was able to cast this anxiety aside when I went and got cancer myself. In a bad case of the universe having a bit of a laugh at my expense, I was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer when I was just embarking upon the edit. But in lots of ways, this was useful in that I was able to throw in all my own experiences; the horror of those sinister nuclear scanning machines, the fear of where the cancer will travel to next. I think I would have been really annoyed about it if the book was already published and sitting on a shelf, but I still had time to use what was happening to me creatively. It was quite therapeutic really! In fact, the paragraph you mentioned above I remember writing while I was having chemo.

I did feel a certain anxiety writing about having cancer when I had never been through such a thing, but I was able to cast this anxiety aside when I went and got cancer myself.

JS: I am so sorry to hear this! Are you okay?

SB: Yes, I’m very well, thank you! The drugs are so good these days. If you’re going to get cancer, breast cancer’s one of the better ones — highly researched, well-funded, all the drugs are on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Also, I’m fortunate to live in Australia and we have fantastic health care here.

Shirley Barrett Recommends Five Horrifying Books That Aren’t By Men

JS: The Bus on Thursday takes the form of Eleanor’s private blog entries. For some readers, this will bring to mind famous epistolary horror novels — Frankenstein, Dracula. Can you talk about your decision to use this particular first-person form?

SB: I was aware of cancer blogs and thought it would be an effective device for Eleanor to recount this story as it unfolds. In fact, it’s really just a journal because she never puts it up on the internet, and of course later in the novel you think, where could she possibly be finding the time to write all this down? But I try not to worry too much about such things! I like writing in the first person, and I have written enough diaries over the years to know how you tend to express yourself — a free use of caps and exclamation marks, a tendency not to care too much about grammar.

JS: What’s been the book’s reception in Talbingo?

SB: To be honest, I don’t know. The book hasn’t been out long, and I haven’t heard. We no longer have any relatives in the area, and I haven’t been there in a while. I have to say I’m a little nervous about it. It’s such a beautiful spot, I can imagine they’d be aghast at having such a mad story set there.

JS: You’re a filmmaker, too — you’ve worked as a screenwriter and a director. How does your professional experience in film transfer helpfully to novel-writing?

SB: Both my novels began as screenplays, and I think it’s a very laborious but quite effective way of going about it! I guess writing a screenplay is like writing a very elaborate outline, so when you sit down to write the novel, you are free to play — you’ve done a lot of the structural work already, you’ve thought the whole thing through visually. And also, you’ve lived with these characters for a long time. So now you get to unleash! To be honest, I find writing a novel utterly liberating after the constraints of screen-writing. But funnily enough, now I am going through the weird process of transposing it back into screenplay form. I’ve sold the television rights, and I’m writing the pilot. I thought it would be a breeze, but it’s not at all. Having gone from screenplay to book, I have traveled much more into Eleanor’s head — now, going back to screenplay, how do you convey all that without resorting to voiceover?

JS: When you first went from screenplay to novel, what were the most surprising changes that occurred? (And now that you’re going back to a screenplay, for the TV pilot — congrats! — what’s changing that’s surprising you?)

SB: In the original screenplay, I breezed through the cancer stuff very quickly and got to Talbingo quick smart. But when I started writing the novel, I realized there was a lot of rich material to be mined in that whole cancer section and I think it goes a long way in informing why Eleanor responds the way she does to everything that happens in Talbingo. Also, I think it helps her earn some sympathy (my mother would not agree. She has no patience for Eleanor’s whining.) And as I mentioned earlier, transposing the novel back to screenplay form, I am really finding her voice much more challenging to nail. I don’t want her to end up as the snarky smart-mouthed female you see so often on TV. She is snarky and smart-mouthed, of course, but somehow in screenplay form, once you type those letters “V/O”, it just seems…..less than..

JS: What are some favorite novels, screenplays, or films that have meant a great deal to you as a writer?

SB: I would say straight off the bat Robert Aickman, a British fantastic fiction writer of the ‘60’s and ‘70’s. His writing is a huge inspiration to me. I discovered his short story “The Hospice” in an anthology, and I think it’s just one of the most extraordinary pieces I’ve ever read. I re-read it regularly, always in the hope that I’m going to finally figure it out — its meaning feels just tantalizingly out of reach! He seems to successfully manage to juggle humor — a very low-key, dry sort of humor — with a powerful creepiness. If you haven’t already read “The Hospice,” I really recommend it as a Robert Aickman starter. And since we’re talking horror, then I would happily volunteer The Shining and Carrie as my two favorites movies in that genre. I saw Carrie at a preview screening when it first came out and absolutely nobody saw that tag ending coming. My sister slid off her seat onto the floor. It’s an amazing piece of film-making, and still stands up brilliantly today. That Brian de Palma really knew what he was doing.

JS: What have you been reading lately that’s stunned you?

SB: Fever Dream by the Argentinian writer Samantha Schweblin. It has this breathless, urgent pace to it and is absolutely unlike anything I’ve ever read before. It grips you with anxiety and dread from the get-go and doesn’t let up for a moment. Really original and yes, stunning.

JS: Other than the pilot for The Bus on Thursday, what are you working on next?

SB: I’ve just finished a non-fiction piece called Dr. Marshall about a Sydney doctor of the 1900s who had a very lucrative sideline in abortions. I first discovered him in the Morgue Register of the day, because he just kept killing all these young women. He was never convicted, although he faced plenty of charges, and even though he was always in the newspapers appearing at inquests every few months, women continued to go to him.

It’s my first attempt at non-fiction, and I’m hoping I’ll get better at it– one day I hope to write a piece about this conman/fraudster/fabulist of the same period whose name shall remain a secret because I don’t want anyone else to write about him before I do!

‘The Bus on Thursday’ is a Funny Horror Novel About Cancer was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : ‘The Bus on Thursday’ is a Funny Horror Novel About Cancer