It has been 19 months since I regularly visited local restaurants in the Bay Area. While I miss the experience of going out with friends and family to enjoy good food, I admit that I am a little shocked at how much I was spending on food and drinks made for me by someone else! Like most of us, I have a few favorite places at different points on the cost scale, and I miss those the most. There’s not a particularly good home replacement for perfectly fried food, an elegantly concocted piece of sushi, or street tacos with filling that has been simmering for 24 hours in proprietary broth.

In other words, I have a very precise list of places I’ll be going once my friends and I feel comfortable visiting restaurants again.

In the meantime, I’ve been visiting my favorite local haunts by exploring their cookbooks. The Bay Area is particularly lucky to have several top-notch restaurants whose chefs enjoy sharing their work not only in person, but also in print.

My favorite example of this came in extremely handy during the “everyone must make their own bread” phase of lockdown. Tartine’s bread is legendary; Bay Area residents reserve loaves days in advance, and you know if you’re at a fancy gathering if you catch a glimpse of a Tartine loaf on the counter. While it’s difficult to replicate professional bread ovens in an apartment, I sure did my best, helped along by the excellent pictures of what bread craftsmanship can be in Tartine: A Classic Revisited.

Another local favorite and staple that I missed with my entire stomach was the stunning Burmese food from Burma Superstar. Burmese food can be tricky to find; it’s not as widespread as many of the other delicious Asian staple restaurants, but because of Myanmar (formerly Burma)’s location nestled among many different ethnic and geographic regions, the food is diverse and spiced in unusual and interesting ways to those of us who are not as adventurous with our Asian cuisine. While I was getting used to being home, it was a challenge to figure out how to feed myself without needing to cook three times a day. I turned several times to the Burma Superstar Cookbook, having scored a bag of rice at Costco just before lockdown. I cannot recommend the firecracker cauliflower highly enough, and I am usually not a firecracker OR a cauliflower fan.

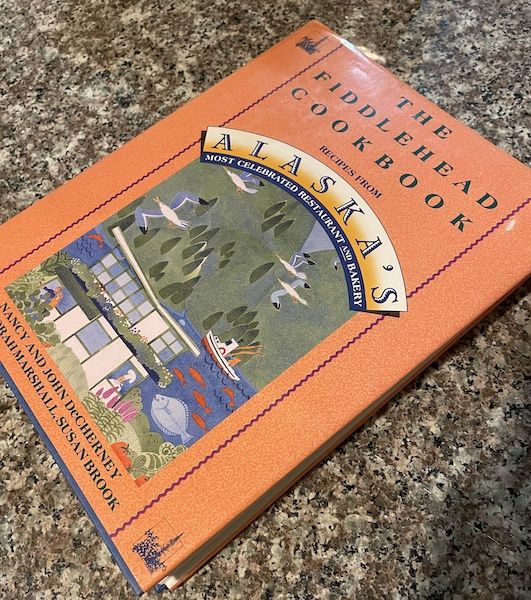

The above are examples of how local cookbooks can keep us connected to places we love, even when we can’t visit them. When I was growing up, the Fiddlehead Restaurant was my parents’ favorite place. I bought their cookbook when I was in high school because their double chocolate cake is to die for, and I am so grateful that I did, because the restaurant closed several years ago and — despite not having been there for probably 20 years — I was bereft. I consoled myself with that cake, along with some of their Fantasy cookies, naturally.

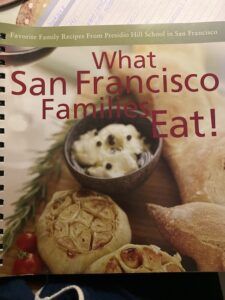

If you’re looking for the most local of cookbooks, look no further than the cookbooks put together by schools, churches, or other groups that are otherwise not primarily brought together by cooking. One of my friends has her children at Presidio Hill School in San Francisco, and she sent me this photo of their school cookbook. The table of contents is full of a wide range of foods, and the descriptions — written by the families — are endearing. People chose precious family recipes to share with their classmates, and while those classmates may not appreciate that gesture now, they certainly will in the future.

These texts, especially the ones put together by schools or other groups, are a wonderful picture of a moment in time. With very few exceptions, food is incredibly transitory. In the short term, you have to eat it before it goes bad; in the long term, our tastes change as we grow and age. But food also brings people together, perhaps more than any other thing that humans do. Everyone has to eat, and doing so in groups is an innate expression of trust. Local cookbooks are a tangible example of that trust, and you can’t go wrong by collecting a few for your own cookbook shelf.