This past winter holiday season, we were rewarded for enduring the year that was 2021 with an adorable gay Christmas romcom, Single All The Way. I was all in for the fun and family and longing that was promised, and it totally delivered on those elements. I was particularly excited about there being a Black love interest in a category of romcoms that only recently started being less white and heteronormative. But as a Black person, a Black woman, I couldn’t help but despair about Nick, the BFF and primary love interest played by the delightful Philemon Chambers.

The character, who could have been played by any actor of any race, doesn’t have any family (his mother has died), does gig work for an app that provides helpers (because he likes to help people), and when he arrives in New Hampshire with his white BFF to spend Christmas with his white family in the whitest state in the country (okay, maybe that’s Rhode Island), is immediately corralled into doing free labor…and then does it again, and again. Oh yeah, sure, he occasionally wears a do-rag, but not a single word is said about his headwear and its presence is uneven at best. Maybe none of this would have struck me so hard if it had been an all white cast, but then…well, we would have been having a different conversation.

This movie, which I still loved for what it was and plan to watch again in the future, made me think about how the same thing plays out in the book genre that is my food and air: romance. Much like Single All the Way and its fellow romantic comedies, holiday or otherwise, genre romance has certain beats to hit in order to make a strong, compelling story:

- Introduce characters who will end up romantic partners

- The meet cute (or turn of events that changes the relationship, if they already know each other)

- Establish why they aren’t or can’t be together

- Put them in a new situation that brings them closer together

- (Occasionally) introduce a secondary love interest

- Something (a fight or misunderstanding, usually) tears them apart

- A grand gesture brings them back together

- And They Lived Happily Ever After (HEA)

Authors can play with this formula to their heart’s content, or even just rip it up and throw it away — as long as there’s an HEA and the romance is at the center of the story, it’s still a romance.

As romance readers make their first forays into diversifying their reading experience, more often than not (thanks to publishing and marketing) they are going to find interracial romance. These could be books written by authors of color or by white authors. More often than not, an interracial romance is going to be a pairing between a BIPOC character and a white character, though sometimes we will get pairings between BIPOC characters of different races. (These are frequently written by authors who are represented by one or both of the characters.) Historically, the most common interracial pairing is between a white character and a Black character, but we have been seeing more across the racial spectrum as we’ve seen more authors across the racial spectrum. And of course, as white authors work to diversify their own worlds, we have also seen them introduce characters of color into their romances as well.

Sometimes, though, that last one doesn’t work as well for me, as a reader.

I love reading romances by authors of color. It doesn’t matter what their background, heritage, or nationality, there’s something particularly engaging about them. Black authors, obviously, will make the worlds that are most familiar to me, including language and speech, family and friend dynamics, and lived experiences as Black folks in the United States. And there is something there in the relationships other racial communities have with each other and with the white majority that rings true when I’m reading books by other BIPOC authors. Whether they write romances between characters in their own communities or across racial lines, I feel a kinship. And one thing that brings that about is the cultural and family expression that comes through so many of those books. That doesn’t mean I don’t love books by white authors featuring white characters; the ones by authors of color just hit different.

One thing that stood out in Single All the Way, and which made me assume it was race-blind casting, is that there is never any reference to Nick’s race or family traditions. The people behind the scenes might have thought this was contributing to the whole colorblind fantasy of it all, but believe me, when you’re surrounded by your white BFF or significant other’s whole white family, in their very white community, somebody’s going to say something. Even a quick “Really? You’re asking my Black friend to be your free handyman?” or something might have made it seem more like the real world. But alas, I don’t write for Netflix. (Seriously, y’all, call me. I’m ready.) And this can also be apparent in interracial romance between a white character and a character of another race that is written by a white author. I’m not saying this is always the case, but sometimes, the representation doesn’t ring true to me, even when it’s a character with whom I don’t share a racial or cultural background.

I recently read two books back to back in which this contrast felt particularly highlighted. Both by debut authors, they were very different stories for very different audiences. Neither book had a Black protagonist or love interest, but I feel like I can talk about them from the perspective of a critical reader and a woman of color, familiar with racial power dynamics.

The first book was Alice Cochrun’s The Charm Offensive. This wonderful, darling book is the story of a producer on the set of a Bachelor-style reality dating show called Ever After and the season’s prince, who the producer can’t help falling in love with. We’re introduced to Dev Deshpande, the producer, as a member of a sort of Cabal Of Color on set, as the people he interacts with on a regular basis are mostly non-white. His skin, hair, and eye color are referenced throughout the book.

We learn that his parents both moved to the U.S. from India in an almost throwaway reference, and when we eventually meet them, they’re nice, generic academic parents. He never references culture, food, or the idea of visiting his parents’ home nation. I’m not saying he should be dancing Bollywood style and eating samosas all the time — but there’s something missing, and I can’t tell you what it is. He doesn’t read like a character in a Sonali Dev or Alisha Rai novel. And he doesn’t have to! There are plenty of people, especially first and second generation Americans whose families come from non-white or non “western” countries, who have more mainstream life experiences than others. But you’d think there might be something in his interaction with his family, or his interaction with other people, that might indicate some background or racial makeup that isn’t white.

There’s very little put forth about the racial dynamics between Dev and any of the white characters, even when compared to the other characters of color who have issues on set partially related to their own racial backgrounds. This is especially strange during the denouement, which I won’t talk too much about because I still want you to read it. But Dev could totally have been Dave — change all the skin color references and the throwaway line about his parents being from India, and Dave would just be a generic white dude from South Carolina.

(This is not to say that a character is inauthentic because of the way they’re represented in the book in regards to race-based and place-based history and presence. It’s more that to me, the character would feel more authentic with those extra elements built in. There is no universal experience for a group, whether they are members of a certain race, nationality, or religious group. But there is something that connects them, anyway, especially when they exist in white spaces.)

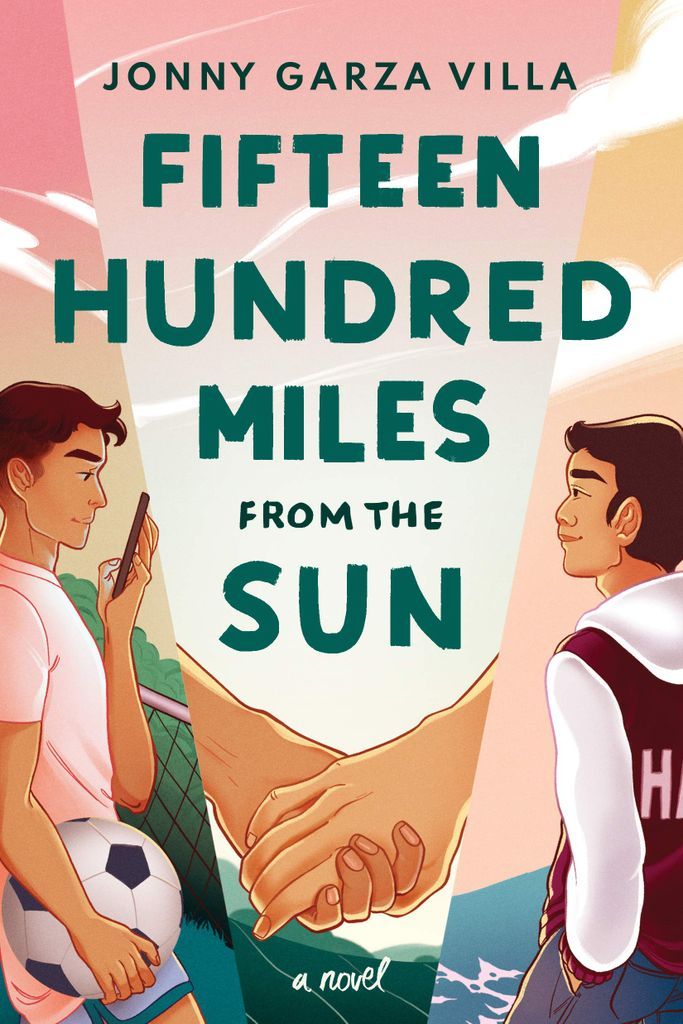

Contrast this reading experience with that of Fifteen Hundred Miles from the Sun, which is a YA novel about a high school senior who drunkenly comes out on Twitter and falls in love with the Twitter mutual across the country who shoots his shot. Julián is Mexican American, as is his family and most of his friends. They don’t speak in Spanish all the time, but they use a lot of slang with Spanish origins and have a shared culture of habits, food, and general understanding. When Jules starts talking more to Mat, who is Vietnamese American, and eventually meets his family, that side of the family is maybe a little less filled out than Jules’s Mexican American family and friends, but still feels like some thought was put into how they were written, and who they were. There is cooking and language and habits, all of which build out a group of people who feel like they come from somewhere beyond the white norm of American representation. And while neither character’s troubles are built on their racial identity, it still comes into play when those troubles are brought to the forefront — particularly Julián’s.

As a college educated, working middle class Black woman who lives in a city where less than 10% of residents can claim the same demographic, I know not every cis Black woman has the same lived experience, even if they check off the same boxes I can. They might have been raised in a different kind of community than I was, or with a different set of rules or language. They might have been raised on different food or been taught different slang. But there’s an element of difference — of Blackness — that we share and that has to be acknowledged, even by someone who doesn’t share that difference, if they are writing stories about us. While race is a social construct, it is still something that contributes to our interactions and experiences, whether good or bad. Our differences are what make us interesting, and our racial background and heritages contribute to those in big and small ways. We don’t live in a colorblind world, so why should we want to read about people who claim to be us, but just have a few factors thrown at our description to explain that we’re not white, but are just like white people?

Every author has their own perspective when it comes to writing about people with their own shared experiences and people who don’t share them. No one can live every life, and that might lead to readers who don’t see authenticity in what they are reading. But sometimes, it becomes more than that. When trying to write diversely, but not particularly making your character more than a brown-painted white character, you’re not bringing into account the culture and experiences that many non-white people have been raised with. That includes smallest things that people from other communities, and the majority culture in particular, might not even realize they’re passing over.

It can become a serious pitfall, but it’s not always noticeable, even as a reader of color. Plenty of people of color have grown up as part of majority culture, especially if that is what their parents or other guardians decided would be best for their own futures. But even then, there is something there that speaks of other, and that’s not a bad thing. So when I, as a reader, see an author produce fully rounded, whole people, who have elements of their separate backgrounds, cultures, and heritage built into not just their looks, but their speech, their food, habits, dreams, desires, and history — the way they interact with the majority white world and that world interacts back — that makes a huge difference in how you might look at everything else going forward.

There’s plenty more to say about interracial romance — why it’s such a big part of mainstream diversity efforts; why so much of it features a white love interest; why the Black Woman / White Man pairing is so popular; why we separate it from Black Romance and Multicultural Romance — but that’s another conversation for another day. Or several conversations. In the meantime, I will continue to keep my eyes open for those examples of romance, written by people of all races, that truly encapsulate the elements of someone’s life that make them stand out as their most authentic selves.

Source : SINGLE ALL THE WAY and the Variables of Interracial Romance