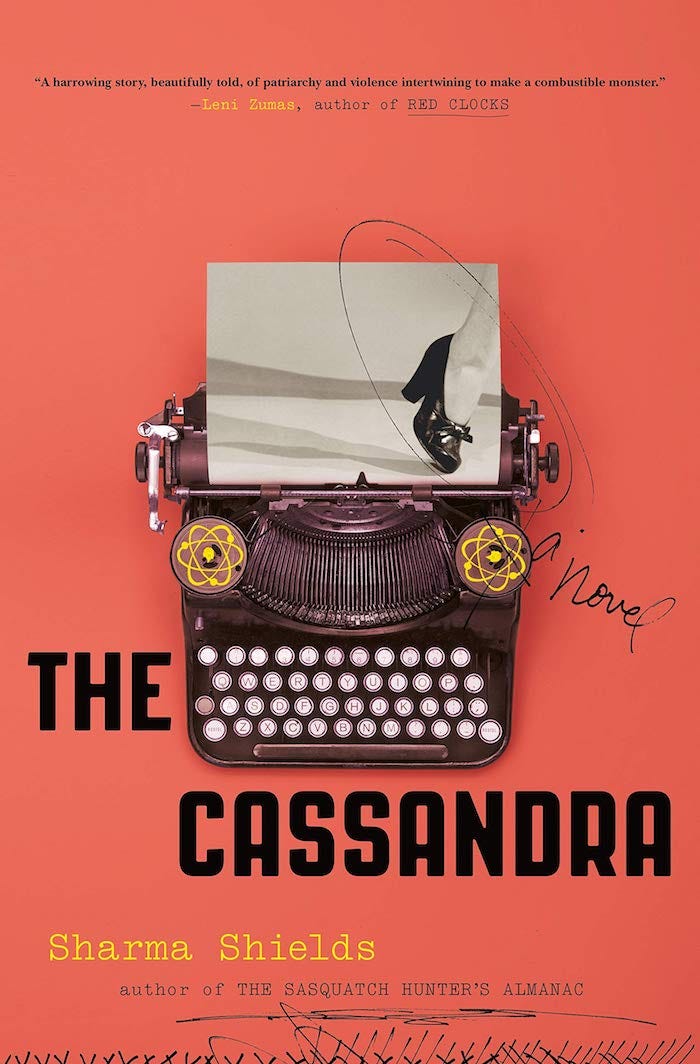

An Excerpt from “The Cassandra” by Sharma Shields Recommended by Kathleen Glasgow

Issue №351

Jump to story

INTRODUCTION BY KATHLEEN GLASGOW

The very first line of Sharma Shield’s new book, The Cassandra, is an ominous, creepy warning of the story to come: “I was at the mercy of the man behind the desk.”

In this era of #MeToo, that sentence put prickles on my neck that lasted until the end of the book, a retelling of the Greek myth of Cassandra, a seer whom no one believed. Our Cassandra in this case is dowdy, awkward Mildred Grove, 18-years-old and fresh from under the thumb of her cruel mother. Mildred has escaped the claustrophobia of her home life for what turns out to be an even more oppressive atmosphere: a secret research facility in a remote south-central Washington State. A clerk in a drugstore tells Mildred the color of the lipstick she’s buying is a “whore’s color.” The man behind the desk at the Hanford facility encourages Mildred to push her chest out, promises she’ll find a husband. Oh, and they’re making plutonium at the facility to use in atomic bombs. It’s 1944. And Mildred Groves, just like Cassandra, can see the future. Will anyone listen?

Can you see where this is going?

The beauty of this read is the way Shields deftly moves between the horrors of so many things: nuclear destruction, patriarchy, sexism, racism. Mildred might have thought she escaped a brutal life, but she’s only found one more dangerous. Like her previous novel, the sorely under-appreciated The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac, in which Bigfoot and domestic discord share the stage, The Cassandra is equal parts mystery, fantasy, genre-bend, and coming-of-age. And when that man behind the desk tells Mildred the perfect female employee is “Chaste. Willing. Smart. Silent,” it’s also a chilling reminder of just how little women’s lives have improved.

Kathleen Glasgow

Author of Girl in Pieces and How to Make Friends With the Dark

The Bottomless Pit

“To Make Men Free” and “Off to the Movies”, an Excerpt from The Cassandra

by Sharma Shields

“To Make Men Free”

I was at the mercy of the man behind the desk. I needed him to see my future as clearly as I saw it. He held four pink digits aloft, ring finger belted by a fat gold band, and listed off the qualities of the ideal working woman.

“Chaste. Willing. Smart. Silent.”

I swallowed his words, coaxed them into my bloodstream, my bones. I crossed my ankles and pinned my knees together, morphing into the exemplary she.

The man eyed me with prideful ownership. “Frankly, Miss Groves, you’re the finest typist we’ve interviewed. Your speed and efficiency are commendable.”

I opened up my shoulders, smiling. “They named me Star Pupil at Omak Secretarial.”

“You’re not a bad-looking girl, you know that?”

“Thank you. How kind of you.”

“A little large. Plumper than some. But a nice enough face.” The man smoothed open the file on his desk. “Good husband stock at Hanford, Miss Groves. Plenty of men to choose from.”

In my lap my hands shook like tender newborn mice. Such sweet, dumb hands. Calm down, you wild darlings. I focused on the man’s sunburnt face. It reminded me of a worm’s face, sleek, thin-lipped, blunt. He was handsome in a wormish way, or wormish in a handsome way. If I squinted just a little, his head melted into a pink oval smudge.

We spoke in a simple recruiting office in my hometown of Omak, Washington. All of Okanogan County was abuzz with the news of job openings at Hanford. It was like this, too, when they started construction at the Grand Coulee Dam. We were patriots. We wanted to throw ourselves into the enterprise. Men and Women, Help Us Win! Work at Hanford Now, the Omak-Okanogan Chronicle urged. I’d snipped out the newspaper article and folded it into my pocketbook, away from Mother’s prying eyes. I was here in secret, and the secrecy delighted me. Goose pimples bubbled up on my forearms and I tapped my fingers across them, tickled by how they transformed my girl flesh into snakeskin.

The room we sat in was crisp and clean, beige-paneled walls, pine floors, plain blue drapes. A war poster hanging behind the recruiter’s worm-head featured a young, attractive woman in uniform, crimson lips, chin nobly lifted, blue eyes snapping and firm, their color enhanced by the stars and stripes rippling behind her.

Her proud expression spoke to me. I’m here, Mildred. I can help you.

I smiled at her. I’m here, too. For you. For all of us.

Aren’t we lucky, her eyes said. If anyone can save them, it’s you.

Above her strong profile it read,

TO MAKE MEN FREE

Enlist in the WAVES Today

“You will share the gratitude of a nation when victory is ours.”

I, myself, wasn’t joining the WAVES, I was joining the civilian force, the Women’s Army Corp — the WACs — but the work at Hanford was just as crucial for the war effort. With the woman in the illustration I shared a gallant dutifulness. I mimicked her then, holding my chin at the same noble angle, lifting my eyebrows with what I imagined was an arcing grace. I wanted to show the recruiter that I was just as earnest and eager as she was to join the fray.

“You’re squirming,” the man said. He smiled with concern, “Are you uncomfortable?”

I assured him I was fine, just excited, and I lowered my gaze. I wore my only good blouse, cornflower blue, and an old wool skirt, brown. The shoes were Mother’s and pinched my feet. One day I planned to buy my very own pair of wedged heels. I’d circled a black pair in the Sears Christmas catalog that I very much liked. They looked just like the famous movie star Susan Peters’s shoes. When Mother had found the page in the catalog, she scolded me for marking it up with ink.

Once, in downtown Spokane, just after we’d visited our cousins, I saw her — Susan Peters! — walking in a similar pair. She was graceful, athletic. I waved at her and she waved back as though we were dear friends. I wanted to speak to her but Martha, my older sister, pulled me away, telling me I was acting like a starstruck silly boob, and I had better stop it before I did something we’d both regret.

Don’t embarrass me, Martha had hissed. Act normal for once, please.

The recruiter cleared his throat, shuffled the papers on the desk, and continued his summary of the Hanford site. I chided myself for my woolgathering. I fought the urge to slap myself and leaned forward clutching my elbows. I hoped I looked alert and intelligent.

“Hanford is a marvel,” the man said, “nearly seven hundred square miles in size, smack dab on the Columbia River. We started construction last year and we’re darn well near finished, which is a miracle in itself. You’ll see what I mean when you see the size of the units. These are giant concrete buildings. They make your Okanogan County courthouse look like a shoe box. We’ve brought in more than forty thousand workers to live at the Hanford Camp, so believe me when I say you’ll have plenty of men to choose from.” He winked here, and I gave a small nod of appreciation. “The work being done is top secret. Frankly, I’m not sure what it’s all about — mum’s the word — but everyone says it will win us the war. I do know that a top United States general is involved, and some of the world’s finest scientists. Construction is being overseen by DuPont. But even these details you must keep top secret, Miss Groves.”

He handed me an informational sheet, and I read it self-consciously, keeping my back straight and my head slightly lifted so that I didn’t give myself, as my sister liked to tease me, too many chins.

To accommodate nearly 50,000 workers, the Hanford Camp is now the third- largest city in Washington State:

8 Mess Halls

110 barracks for men ( for 190 persons each) 57 barracks for women

21 barracks for Negroes

7 barracks for Negro women Plus family huts and trailers

Overall: 1,175 buildings in total for housing and services

There’s a lot of us, so remember: Loose talk helps our enemy, so let’s keep our traps shut!

“What a bold undertaking,” I told him. “What an honor it would be to work there.”

His face crinkled cheerfully. “Regarding your application, I don’t have many reservations, Miss Groves. Your background check is clean. You’ve signed the secrecy documents. The only concern raised was about your questionnaire. A few of your answers were — how shall I put it? Unique.”

For a moment my future darkened. I had agonized over my application. I couldn’t imagine anything amiss.

“For example,” he said, lifting a sheet of paper up to his nose, “your response to the request for relevant job experience, if any, was, ‘I have imagined myself in a giant number of jobs, some of them impossible, some of them quite easy, and in my imaginings I’ve always done well by them, impossible or no.’ This statement struck some of the committee members as a wayward answer, Miss Groves. Would have been better to just state ‘No relevant job experience.’ Most of the women answering the charge are lacking in it, you realize.”

“Yes, I understand.” My eyelid violently twitched.

“And then there was your response to the question about your weaknesses. You wrote, and I quote, ‘I have made a big mistake in my life and it haunts me. Sometimes when I make a mistake this large it stays with me for a long time. I wish I got over things quickly.’”

I waited for him to continue, holding my breath. I thought of Mother, of the splash and crunch of bone when I pushed her down the bank into the river. I wondered if he could see her shadow flicker across my face, hear faintly the sound of her muffled scream.

“Lastly, when you were asked if there was anything you wished to add, you wrote, ‘I only wish to say how confident I am that I will be the best fit for this position. I have seen myself there as clear as day. I dream about it. I know for a fact that you will hire me. I will not let you down.’” He looked up at me with his smooth worm’s face, his graying eyebrows raised slightly. He seemed more amused than troubled.

“I don’t need to tell you,” he continued, “that we need workers with very sound minds for this position, Miss Groves. We need reliability and obedience. Your confidence struck some of our committee as arrogance. And one or two of the men wondered about your rationality.”

“Omak Secretarial told us to be forthright and self-assured in our applications, sir. If I overdid it, I apologize.”

The recruiter cocked his head. “Personally, I found it refreshing. You should see some of the anxious girls we get in here. A bit of confidence is a good thing.”

I stayed silent, balancing the line of my mouth on a tightrope of strength and humility. I knew better than to tell him the truth, that I had dreamed about Hanford, that I had seen myself there. I had, in fact, sleepwalked into Eastside Park, awaking with a start beside a grove of black cottonwoods, the trees shedding puffs of starlight all around me, the wind whispering through the branches of my fate. He would hire me because I had envisioned it, and my visions always came true in one form or another.

As if sensing my memory, the recruiter’s face tightened. “You can no doubt imagine the outcome if secrets were shared with the feeble-minded.”

I leaned forward gravely. “Our very nation would be destroyed, sir.”

The recruiter’s visage softened into an approving pink mud. I’d made a good impression. He sat back in his chair and smiled.

“The truth is,” he said, “when I read your comments I thought, now here’s someone who really gets it. The confidence might bother some of my colleagues, but these times call for backbone. For attack! We should bomb those Germans to smithereens, wouldn’t you agree?”

“Oh, yes,” I said, “most certainly. Bombs away.”

“You’re an exceptional sort of girl, Miss Groves, a skilled typist and a clear patriot. You won’t meet a more outstanding judge of character than myself, and given your excellent response in person, I’m happy to stamp my approval on your form.” He grinned at me, the grin of a generous benefactor. “I’m hiring you as a typist for Hanford. Welcome to the Women’s Army Corps.”

I closed my eyes for a moment and took a deep breath. My limbs buzzed with elation. “Oh, sir,” I said, opening my eyes. “I’m so grateful.” I’d never stepped foot outside of Omak, but now I’d be a sophisticated, working woman at Hanford, joining the fight with the Allies and making the world a better place. I teared up, not sure if I should lean across the desk and shake his hand or if I should just stay rooted to my seat, trembling with destiny.

“I’m thrilled. You have no idea.”

“I tell every young person who comes through here, ‘Stand tall. You’re a hero.’”

He lifted gracefully from his chair as though showing me how to do it. I rose, too, more clumsily.

“Stand tall, Miss Groves. Shoulders back, chest forward. There you are. Well, almost. Good enough, anyway. Of course I can’t tell you the particulars of the work, but let me just say, you’ve chosen a lofty vocation. Selfless girls like you are one of the many reasons we’ll win this war.”

At the word selfless, I heard in the stunned silence of my mind Mother’s dark laughter.

He offered me a sheaf of introductory papers and a voucher for a bus ticket. I accepted these, allowing his warm hand to grasp my elbow. He guided me toward the door and then released me.

“You’ll make some young man very happy one day, Miss Groves. Patriotic girls always do. Whatever you do, hold on to that innocence.” Imagining Mother and Martha overhearing this description of me was almost more than I could bear. They would fall upon the recruiter and tear him apart for his mistake.

“I’ll hold on to it,” I said. “I promise.” “Good girl. And good luck.”

I left his office a new woman, a WAC, a worker, a patriot, a selfless innocent — a warrior ready for battle.

“Off to the Movies”

I stopped at the drugstore on the way home and bought myself a cola and a tube of red lipstick. Mother gave me a small allowance once a month. I’d used almost all of it on these two items, but I wouldn’t need her money now, I’d soon be making my own. Old Mrs. Brown, who ran the shop, peered at the lipstick tube and grimaced.

“A whore’s color,” she said. “Tell me this isn’t for you, Mildred, dear.”

I tucked my chin. “It’s a gift for a friend.”

She handed it back to me. “You shouldn’t spend your money on such things during wartime. God prefers a pale mouth. You don’t want men to get ideas.”

I opened my pocketbook and counted out the change. “Thank you, Mrs. Brown.”

“Take care of yourself, dear girl. Send your mother my regards.”

I drank my cola on the way home, accidentally smashing the bottle into my front teeth so that my whole head buzzed.

I forgot to tell Mrs. Brown good-bye.

She would scold me for leaving, but what if I never saw her again?

Silly Mildred! You’ll see her again. Of course you will.

I quickened my pace, half-walking, half-skipping. It was pleasantly hot and dry and the cola was cold and fizzy in my throat. I opened up my arms and spun about, just once. Another spin and I would lift off of the sidewalk and corkscrew into the fat diamond-bright sky.

Omak was a small town nestled in the foothills of the Okanogan Highlands. Four a couple of short months in the spring, it was a very pretty place, verdant and alive with birdsong, but the winters were harsh and the summers harsher, so dry that you inhaled the heat like a knife. Canada was a short drive to the north. Hanford, I’d learned, was three hours south, in a similarly arid place. This would give me an advantage, accustomed as I already was to the ungracious environment of Central Washington State.

The sum total of the neighborhoods in Omak were modest, and our street was no different. We lived in a white house on the busy main road, surrounded by other small, simple houses. What set our home apart was the large garden bordering the yard, which Father, before his death, tended obsessively. Throughout my childhood it teemed with perennials, allium, aster, lupine, and coneflower, and the north-facing plot grew heavy and green in the summer, laden with vegetables and fruits. On the weekends, he would sell bulbs from his abundant perennials, putting out a handwritten sign, bulbs, ten cents a dozen, and cars would pull up all day long to purchase them. I liked to sit in the lawn in my bare feet and watch people unfold from their vehicles, usually with exclamations of awe or envy at my father’s green thumb.

Our town bordered the westernmost edge of the Colville Reservation, made up of various tribes like the Nespelem, Sanpoil, and Nez Percé. Our region was most famous for the Omak Stampede and the Suicide Race, where men would urge horses down the perilous banks of Suicide Hill, plunging into the Okanogan River and crossing in a dead sprint to the finish line on the other side. Our neighbor, Claire Pentz, was the rodeo publicist, and she started the race in 1935 as a way to drum up excitement for the stampede. She said it was inspired by the Indian endurance races, and she called it a cultural event. It was a thrill to watch the wet horses gallop with their riders the last five hundred yards into the rodeo arena, but the year before my father died was also the year the race killed two horses, one from a broken neck and another from a gunshot to the head after she broke her leg, and then Mother refused to attend.

After that, some of our neighbors muttered, “The barbarity of the savages,” but Father argued with them about it.

“Blame Claire,” he would say. “She’s the one who made this, all for rodeo money. And she’s not Indian.”

But I knew he secretly looked forward to watching the races, and he was proud of the toughness of the men here, even though he would never willingly ride a horse down Suicide Hill, or even canter on a horse bareback, being constructed of what he once described to me as “sensitive bird bones.”

No one who saw me would accuse me of having bird bones, but I was sure my whole self was cluttered with them, my brain and my heart each their own nest of delicate ivory rattles that jostled and clicked together when I moved too quickly. As a young girl, I ached over paper cuts and whined when I lifted anything too cumbersome. A casual insult — eager beaver, fathead, fuddy-duddy — pained me like a toothache for days. My mother was made of tough bear meat: solid-fleshed, big-backed, firm as she was certain. Her shoulder-length hair was so dark brown it was nearly black, and she wore it styled closely to her face, without any of the rolls or curls that were popular at the time. Despite her complaining, I always had the impression that little bothered her — insults, mistakes, the stupidity of other people — she took nothing personally. Life, I assumed, would be easier to navigate with an unforgiving nature.

It doesn’t matter now, I told myself, returning to this ordinary street in Omak on this hot summer day. I’m going away from all of this. I’m snaking out of my old skin to become a bigger, better self.

I reached our front lawn. The neighbor boy had mown it yesterday It looked neat and comfortable and I thought about sprawling out on the green, uniform blades and enjoying my afternoon here in peace, but there was Mother, sitting very still on the porch, wrapped in a thick blanket.

“Oh, Mother,” I said. “Are you unwell?”

She coughed and drew the blanket tighter around her shoulders. “I have the sweats.”

“Mother, darling, it’s ninety degrees and you’re wrapped in a quilt.”

Mother scowled. “Mrs. Brown just phoned. She said you bought a whore’s lipstick. She said I ought to know. The whole town heard about it on the party line.”

“It was a gift for a friend. I already gave it to her on my way here. It’s her birthday.”

“You have no friends,” Mother said.

This was true: My classmates in school had been impatient with me if not exactly unkind. And now that I was older and more confident, maybe even worthy of a friend or two, I was alone with Mother.

“Allison,” I told her, recalling a girl from high school with lustrous hair. “Allison Granger, who lives a block south from here, and who I saw at the church picnic. She has three men asking for her hand — three! — and she says it’s all because of her dark red tubes of lipstick.”

The uneven plate of Mother’s face splintered into a sneer. “You have the devil’s imagination, Mildred. Allison Granger lives in Airway Heights now. I saw her mother just the other day. She told me that Allison’s married a lieutenant colonel. Imagine how proud her mother must be.”

I listened to this quietly, without comment.

“Forget it.” Mother shifted in the old blanket, grimacing. “I’m unwell. I have the sweats. Help me inside, Mildred, before I faint.”

“You need a glass of cold water. Let’s get you out of that quilt.”

“I’ve never been so sick. I’m dizzy.”

“Here, Mother, take my arm.”

“Mildred, you’re the most ungrateful daughter who has ever lived.”

“That’s it, Mother, take my arm. Come inside now.

“What are you crying for? You’re upsetting me.”

I wasn’t crying, not really, I was simply emoting, and that emotion ran like water down my cheeks. Next week I would leave, without saying good-bye to Mother, which I felt horrible about, but it was no use divulging my departure; she controlled me like a marionette. She would lift a finger and yank the string attached to my chest and I would pivot. I would stay, hatefully.

No, I had a plan: The morning before my departure I would post a letter to my sister, Martha. She would receive it the following day and learn that I was gone. It would be too late for her to stop me. She would come and check on Mother, begrudgingly, I knew, but I’d been caretaker long enough. It was time to live my own life. They didn’t think I was capable of it. They thought I was better off locked away with Mother, away from any true experiences of my own. For a long time — riddled with guilt after I’d harmed her — I trusted them, and I served Mother dutifully. I cooked and cleaned and cared for her, answering her every need even when her requests became ridiculous.

I had done enough.

I would continue to serve her now, but in a different way. I would send money from every paycheck to them, more money than they’d ever seen in their entire lives. And when I met my husband and had my children, we would return to visit, and then I would apologize to Mrs. Brown for never saying good-bye, and she would apologize to me for being such a grumpy tattletale, and everyone would be very pleased with me and all would be well. Mother would be beside herself with the beauty of our children — her grandchildren! — and she would thank me for growing into such a responsible and independent young lady. And my sister would say, jealously, Why is your husband not old and bald, like my husband, and why are your children so kind and generous, unlike my children? and I would shrug and embrace her and tell her no matter, that I loved her and her old bald husband and her wretched children, and she would say, Oh, Mildred, I love you, too, and I admire you so.

“I need to go to the toilet,” Mother said, loudly.

I had just settled her on the couch with her blanket and her pillows and a glass of cold water.

“Right now?” I asked her.

“No, next week, Einstein.”

“Okay, Mother. Come on. Take my arm again.”

“Are you still crying? Your moods today! You’re making me nervous. What’s going on in that ferret brain of yours?”

Good-bye, Mother!

I waited outside the door for her to wipe herself, for her to flush, so that I could help her back to the couch and make her a healthy lunch. I brought my hands to my mouth and tried to shove my happiness back down my throat. The tears were gone. Now I was brimming with laughter.

Good-bye and good-bye and good-bye!

“Mildred,” Mother said sharply. “Are you giggling? Get in here and help me clean up. Jumping Jehoshaphat, I’ve gone and made an absolute mess.”

I forced myself to remain solemn. I squared my shoulders and lifted my chin. I went in to help poor Mother.

A few mornings later I pinned my handkerchief around my head and put on, again, my good blue blouse and wool skirt. I went downstairs to check on Mother one last time.

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her.

She lay on the davenport, a wet washcloth over her eyes. Her graying hair hung in tangles around her big face, and I reminded myself to give it a good combing before I left.

“I’m at death’s door,” she said. “But otherwise I’m fine.”

“Is it a headache?”

“No, it’s a splinter in my foot.” She tore the washcloth off from her forehead and glared at me with moist eyes. “Yes, it’s a headache, Mildred. If you were a good girl, you’d fetch me an aspirin.”

I fetched her one. I was wearing my black driving gloves and worried what she’d say when she saw them, but she accepted the aspirin without comment.

“Let me get you a glass of water,” I said.

“I’ve already swallowed it.”

“I’ll get you one. For later, if you need it.”

“Mildred, you know I hate it when you do unnecessary things for me.”

“For later, Mother.” I shouldn’t have said what I said next. It was some sort of mischief rising in me. “I might be gone a long time.”

“Don’t say that,” she said, and she looked at me with a mixture of panic and derision. “Don’t tell me you’re going to spend all day at the movies again, watching the same film half a dozen times? You’ll bring on another one of my heart attacks. I hate how you envy those silly starlets.”

“No, I’m not doing that, Mother. I promise.”

I didn’t point out that she’d never had a heart attack.

I went to the kitchen and drew a glass of water for her and returned to set it on the coffee table. Good-bye, old table! This was where I had once cut out paper dolls with my older sister. At that age Martha had gushed over my precision. She had asked me to help her and I was glad to do it. Good-bye, kind memories!

I placed the water close enough to Mother so that she could reach it easily without having to sit up.

Well, there, I thought. Maybe I should give her a little food, too?

I went to the pantry and found some saltines and spread a handful across a plate and brought that to her. She watched all of this silently, sulking.

The phone rang. Mother reapplied the washcloth to her face, waving at the noise dismissively.

I went to the phone and brought the receiver to my ear.

“Mildred,” my sister said. “I’m livid. You stay right there. Walter’s getting the car. We’re coming straight over.

“Oh, hello, Martha,” I said. I inwardly cursed the postal service’s promptness. I hadn’t expected them to deliver the mail so early. “So good to hear your voice. How are the children?”

From the couch Mother groaned.

“Don’t act like the Innocent Nancy here, Mildred,” Martha said. “I’ve read your horrible letter. You can’t, you simply can’t upset Mother like this. She’s an old woman and she’s alone in the world. And to expect me to uproot my life in this way, when I have children, Mildred, when I have a husband! It’s just extraordinary! It’s like I always say, if only you had children, if only you had a husband, you would understand, you would know implicitly what I mean.”

Mother rose up on one elbow, turning her head toward me with the washcloth still smashed over her face. “Tell your sister I can hear her squawking from across the room. It hurts my sensitive ears. Tell her she sounds like a drunk banshee.”

“Marthie,” I said, interrupting my sister gently, “Mother says you sound like a drunk banshee.”

“Hand the phone to Mother. Have you told her yet? No, of course not. It’s just like you, to run away from things like a coward. You’re the most cowardly person I know, Mildred. Put Mother on the phone. She’ll scream some sense into you. And Walter and I will get in the car right now, with the kids, we’ll be there in twenty minutes flat — ”

“Mother,” I said, “Martha wants to speak with you.”

“No. Absolutely not. You deal with her, Mildred. As if I don’t have enough on my hands. Tell her I have a terrible headache.”

“She won’t come to the phone, Martha. She has a terrible headache. I’m sorry. And now I really must be going.” I glanced at Mother, who was relaxed again, lying flat on the couch and nibbling on a saltine. “I’m going to the movies. I’m going to the movies for a very long time. Good- bye, darling.”

“You won’t go through with it. You’ve never gone through with anything in your whole entire life.”

I hung up, trembling with relief.

I kissed Mother. “Good-bye.” I tried not to sound too meaningful.

She refused to remove the washcloth, but she accepted the kiss graciously enough.

“You’ll rot your ferret’s brain with those movies, Mildred.”

Her voice was not unkind. It was not such a bad way to leave her.

And then I went out the front door, leaving it unlocked for Martha and Walter, even though they had their own key, and I went down the cement stairs and retrieved my little suitcase, which I’d hidden earlier that morning beneath the forsythia. My father had died pruning this bush — felled on the instant by a massive stroke — but it remained my favorite plant here, so brilliant in spring and so brilliant now, again, in the early fall. Beneath the bright leaves, the limbs looked like Father’s thin arms, reaching skyward, surrendering. When I was very little, he’d called me whip-smart, but Mother had demurred. She can see the future, this girl, he’d said. He was right. I could. But Mother had told him that there was no place in the world for knowledgeable women; he should be wary of encouraging such nonsense. Foresight won’t do a woman any good, she’d said. It will only double her pain. The forsythia shook in the breeze, as if to deny this memory. I backed away from it with a respectful nod of my head.

The luggage handle felt good in my palm, hard and solid like a well-executed plan. I’d packed very lightly, with only a few clothes, an old pair of winter boots, my papers, my red tube of lipstick, and my pocketbook. Within was my bus voucher. I hurried across the street, toward the station. Only a few minutes remained. I couldn’t be late.

Martha was wrong: I’d never been so committed to anything in my entire life.

About the Author

Sharma Shields is the author of a short story collection, Favorite Monster as well as two novels, The Sasquatch Hunter’s Almanac and most recently, The Cassandra. Sharma’s writing has appeared in Electric Lit, Slice, The New York Times, Kenyon Review, Iowa Review, Fugue, and elsewhere and has garnered such awards as the 2016 Washington State Book Award, the Autumn House Fiction Prize, the Tim McGinnis Award for Humor, a Grant for Artist Projects from Artist Trust, and the A.B. Guthrie Award for Outstanding Prose. She received her B.A. in English Literature from the University of Washington (2000) and her MFA from the University of Montana (2004). Sharma has worked in independent bookstores and public libraries throughout Washington State and lives in Spokane with her husband and two young children. Sharma is the President of the Board of the Friends of the Spokane County Library District.

About the Recommender

Kathleen Glasgow is the author of the New York Times best-selling novel, Girl in Pieces. She lives in Arizona. Her second young adult novel, How to Make Friends With the Dark, will be published by Delacorte/Random House in April 2019.

About Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading is the weekly fiction magazine of Electric Literature, publishing here every Wednesday morning. In addition to featuring our own recommendations of original, previously unpublished fiction, we invite established authors, indie presses, and literary magazines to recommend great work from their pages, past and present. For access to year-round submissions, join our membership program on Drip, and follow Recommended Reading on Medium to get every issue straight to your feed. Recommended Reading is supported by the Amazon Literary Partnership, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. For other links from Electric Literature, follow us, or sign up for our eNewsletter.

Excerpted from The Cassandra: A Novel by Sharma Shields, published by Henry Holt and Company February 12th 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Sharma Shields. All rights reserved.

Selfless Girls Will Win Us the War was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Selfless Girls Will Win Us the War