PEN America released their latest report on the state of school book bans, showcasing a 33% increase in the number of books banned in the 2022-2023 school year compared to the previous school year. Florida leads the U.S. in book bans, with 40% of bans taking place in the state. Florida is the home of Moms For Liberty and has implemented a slate of new state laws and statutes to make book banning easier than it is in other states. Many of these laws have been mirrored in other states, including Iowa, and many of the books being challenged and banned in schools are having the rationale for their removal tied to the use of Book Looks, the volunteer-created database with ties to Moms for Liberty.

PEN began to record public school book bans in July 2021 and, to date, has tallied 6,000 bans. Over 3,300 happened in the 2022-2023 school year alone, including 1,557 unique titles. The organization for free expression defines a book ban as a book removed from school library or classroom shelves, including titles that were removed while being reviewed following a challenge.

Some of the data from the report includes:

- 1,406 book ban cases in Florida, followed by 625 bans in Texas, 333 bans in Missouri, 281 bans in Utah, and 186 book bans in Pennsylvania.

- More than 75% of the books banned are young adult books, middle grade books, chapter books, or picture books. The books being banned in schools are those published specifically for these audiences.

- There was a 400% increase in book bans from school libraries and classrooms in the last school year, compared to the previous.

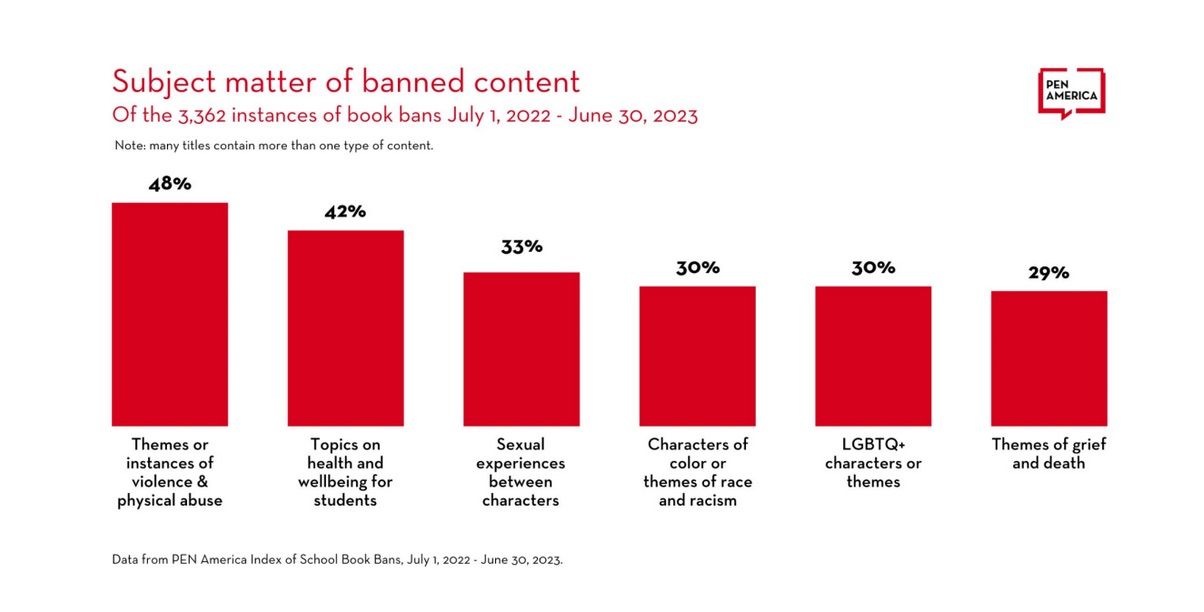

- Almost half of the books banned in the 2022-2023 school year included themes of physical violence. This includes books about sexual violence and assault. 30% of those books include characters of color and themes of race and racism; 30% represent LGBTQ+ identities; and 6% include a transgender character.

- In the 153 school districts across the country that banned a book during the 2022-23 school year, 80% have a chapter or local affiliate nearby of one or more of the three most prominent national groups pushing for book bans — Moms for Liberty, Citizens Defending Freedom, and Parents’ Rights in Education. These districts are where 86% of book bans have occurred. In other words, the bulk of book bans are happening where book banning groups are operating.

“Hyperbolic and misleading rhetoric continues to ignite fear over the types of books in schools. And yet, 75 percent of all banned books are specifically written and selected for young audiences,” explained Kasey Meehan, program director for PEN’s Freedom to Read Program. “Florida isn’t an anomaly — it’s providing a playbook for other states to follow suit. Students have been using their voices for months in resisting coordinated efforts to suppress teaching and learning about certain stories, identities, and histories; it’s time we follow their lead.”

PEN’s report includes several powerful graphics showcasing the ways successful book bans play out across the country.

|

|

It is clear that states with restrictive book policies play a role in the number of books being banned.

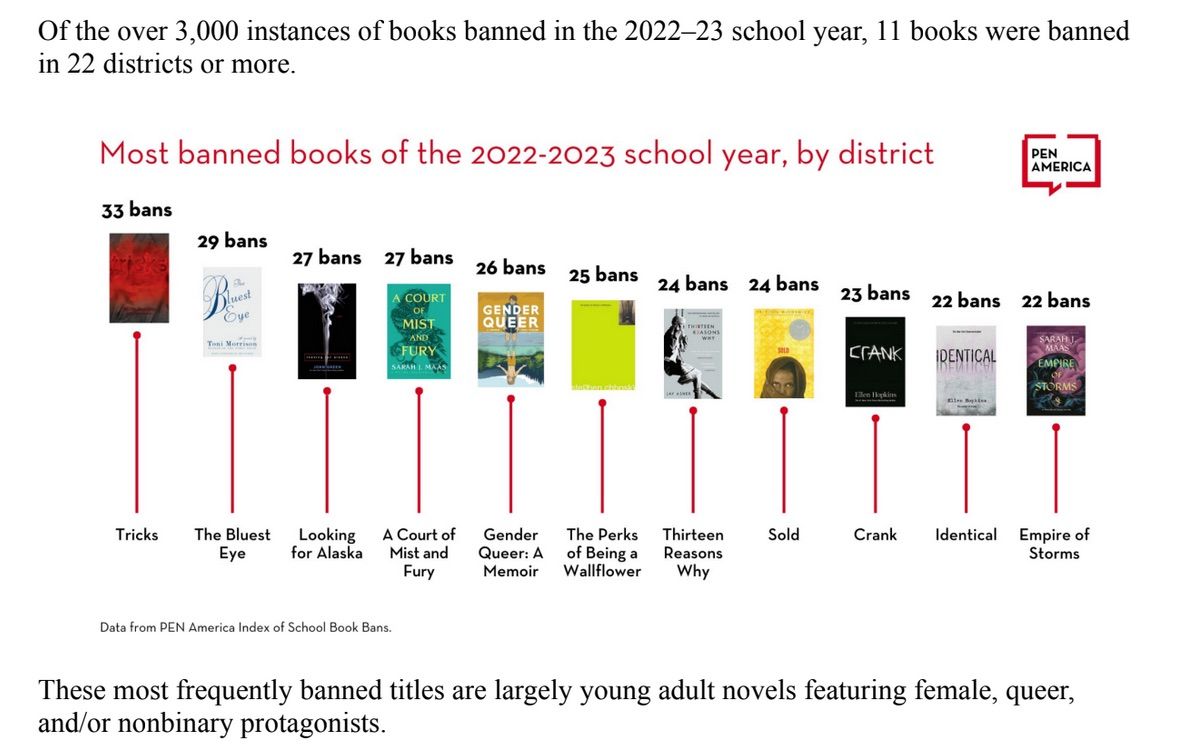

This is the first year in this latest wave of book censorship that books that focus on identity—racial, gender, or sexual—are not at the top of the list of banned books. Instead, books about violence top the list, though, as noted above, many of those books include characters of minority genders or races.

|

Following closely behind books with themes of violence and abuse are those which explore health and well-being. These are the books exploring puberty, sexual education, and the far-right’s definition of “social-emotional learning.”

It should come as little surprise, given the current trends in book bans, that the majority of books being banned are not new books. If anything, the books being banned are now even older than the ones being targeted in just the previous year. PEN found Ellen Hopkins to be the most frequently banned author, with her 2009 novel Tricks topping the list.

|

The average publication date of the most banned books is 2005, making them an average of 18 years old.

“[I]t’s disappointing to see such a steep rise in the banning and restriction of books. We should trust our teachers and librarians to do their jobs. If you have a worldview that can be undone by a book, I would submit that the problem is not with the book,” said YA author John Green, whose Looking for Alaska is at the top of the most banned books list for the previous school year.

One highlight of the report is that it showcases student response to book bans; where we see adults demanding “parental rights” when it comes to deciding what books should or should not be allowed in schools, we are seeing more young people standing up and defending their rights and their right to access books at schools. They are creating student groups—see PARU at Central York, among several others—to rally around anti-censorship efforts, including showing up to school board meetings, staging protests, and more.

“Those who are bent on the suppression of stories and ideas are turning our schools into battlegrounds, compounding post-pandemic learning loss, driving teachers out of the classroom and denying the joy of reading to our kids. By depriving a rising generation of the freedom to read, these bans are eating away at the foundations of our democracy,” said Suzanne Nossel, Chief Executive Officer of PEN America.

You can read PEN America’s full report, “Banned in the USA: The Mounting Pressure to Censor,” here.