The author of “Bookends” on fatherhood, literary citizenship, and the seductiveness of smartphones

When Electric Literature was invited to The MacDowell Colony’s December event for Michael Chabon’s special edition book project, Bookends, I was confused. Wasn’t MacDowell a writing residency in New Hampshire? What were they doing in this big noisy city? It turns out The MacDowell Colony’s mission extends beyond the (somewhat legendary) residency, and their new space at West 23rd St. and 10th Ave. is part of that larger project to encourage collaborations among artists and community for their work.

With the addition of the Chelsea space, The MacDowell Colony hopes to bridge the gap between the idyllic but isolated New Hampshire colony, whose cachet comes in part from how insulated it is from the demands of the real world, and the broader public. It’s a place where people will be able to discover new artists through panel discussions, performances, readings, exhibitions and more. And like the residency, it also fosters collaboration within the artistic and literary worlds.

Chabon, the chairman of The MacDowell Colony, opened the event by highlighting the work MacDowell has made possible for him and others through the rare gift of time. For most, it’s an invaluable moment to finish a work that demands finishing. But for others, something strange happens: A poet may discover what she actually wants to create is a project in collaboration with a composer she met over dinner. An architect leaves with a series of paintings. A composer leaves with a novel. The sheer quantity of time gives artists permission to interrogate their work and discover new directions, even new disciplines for it, in collaboration with others. As Chabon began to read from his collection, I could see the scaffolding of the literary community come into view. Had I but world enough and time, I wondered, what would I make? And with whom?

Michael Chabon and I spoke before the event on the relationship between writing and literary citizenship, how to keep discovery alive, and why we all need to put our phones away.

Erin Bartnett: Writing about motherhood has reached a kind of zenith, and you’ve written so deftly about fatherhood. What do you see as the interplay between those two roles in life and in fiction?

Michael Chabon: I think part of being a writer, regardless of gender, is trying to get more material to write about. And I think it’s inevitable–as men have increasingly become involved in the work of childrearing, it was inevitable, simply because of that brute economics. And I don’t mean economics in the monetary sense–but, there’s always a scarcity of material. So you have this whole load of material, and it’s very natural but also sort of necessary sometimes: “What am I going to write about?” Or you notice this thing emerges in relation to one of your kids, and you just think, “Oh, I’d like to write about that.” I think for me it was natural: here’s material, I’m going to use it in some way, both in my fiction and in nonfiction.

But also, I had a column in Details magazine and I frequently would write about aspects of being a father, being a parent, there. And it did feel like–not that I had the field to myself, entirely–but it did feel like it was very under-trafficked still. And so that’s always appealing, when you feel like you’ve got something to say about something, and you haven’t seen it said too much before in quite the same way. Male writers of prior generations, it just wasn’t–they were men of their generation. It wasn’t part of their lives. For example, I’ve written about my dad. He was–by today’s standards–he was not a good dad in the most everyday sense of the word. He didn’t touch a diaper in his life. He never changed a diaper. When the baby needed to be changed, he’d just hand him to my mom, and that was that. That wouldn’t fly today, I don’t think, in most partnerships. But that was probably true for most men of that time. Whether it was your Bellows, or your Updikes, or whoever. Changing a diaper, to take the one example, just wasn’t part of their experience. For me, it is a part of my experience, so I’m going to write about it.

It’s inevitable as men have increasingly become involved in the work of childrearing that we start writing about fatherhood.

EB: I was struck by this moment in your interview with Fatherly when you talked about about your kids’ view on the future that is kind of pessimistic. You refuse that view. I understand the inclination toward pessimism very well, but obviously want to resist that urge, too. How do you think literature can contribute to that resistance, can combat anti-semitism, xenophobia, and just the general malaise of now?

MC: The thing that I believe about literature more than any other art form, is that it works by putting you into someone else’s shoes. It only works–that’s how it works–by putting you into the mind and the experience of another. When you pick up a novel, and start reading–whether it’s the character living in a time, living in a place, living in a set of circumstances that are completely alien from those that you live in, or whether the author his or herself is writing from a completely different experience–as soon as you immerse yourself in the narrative, as a reader, you are living another life, another person’s life. And there is only one way to do that that we’ve ever invented, in the whole history of the human race, and that’s through literature. Watching a movie is different. Other art forms give you other kinds of points of view on experience not your own, but not in the same sense of that vicarious experience of another consciousness. And I do believe the more you are exposed to that experience, the greater your capacity to imagine the lives of the people around you becomes. Whether those are the people in your own immediate circumstances, or people you pass on the street who are coming from completely different experiences than yours. I think it does strengthen your imaginative muscle, and by strengthening that muscle, it then increases your capacity for empathy. I really do believe that. I’d be very surprised if the world’s torturers spend a lot of time reading literature. The capacity to detach yourself, to punish another person and to see them as less than you, less than human, I’d like to think that’s harder to do if you’ve been exposed to a lot of literature.

Other art forms give you other kinds of points of view on experience but only literature gives the vicarious experience of another consciousness.

EB: Writing is a solitary act, but one that does depend, to my mind, on a community for the writing we put out into the world, a kind of literary citizenship we’re required to take up in one way or another. What is the relationship between the writing and community for you? Where does literary citizenship play into your writing career?

MC: I think you can have the first without the second. And most people, I would imagine — certainly when it comes to writing fiction, maybe it’s different for other kinds of writing — but I think people who become writers tend to be, without overgeneralizing, people who like to be by themselves. People who enjoy their own company or are comfortable being alone. People who, as kids, lived in their heads, and played in imaginary lands, and drew maps of imaginary countries. That’s a kind of paracosmic idea of play, and living in this imagined world by yourself, is, I think, a driving impulse to become a writer.

Writing is, like you say, a very solitary business. And people who do well at it, I mean not financially but creatively, are people who probably are less likely to stand up on a soapbox, or be on the barricades, or lead a march or a protest. While that does happen, I don’t think the responsibility for that kind of activity — to lead a resistance of some kind — I don’t think that’s unique to writers, or even to artists. We all have that responsibility. But it might come less easily to writers than other kinds of people. It’s definitely something that, just speaking for me, I’ve had to learn how to do, how to be that way. It doesn’t come naturally to me.

EB: To be alone or to be a part of the community?

MC: To be part of the community. I’m naturally a very shy person. And I would much prefer not to meet people, not to have to talk to people. Like at parties, I’d much rather be standing in the corner. And I’ve had to learn and fight to overcome that. It’s partly the process of taking on responsibilities as I’ve gotten older. But I really did have to learn how to do it, grow into it. To enter into a room full of people and speak up about something is not part of… to me I don’t think it’s part of a writer’s toolkit. I think it’s definitely another skill set, completely. And some people, I’m sure some writers have both naturally. But I am not one of them.

For example, to be a Chairman of the Board of The MacDowell Colony. When the phone call came it was a message on my answering machine. That’s how long ago it was, 10 years ago, people still used answering machines. And it was Cheryl Young, MacDowell’s Executive Director. She said, “Michael, you’ve probably heard Robin MacNeil’s stepping down as Chair of the Board and I was hoping we could talk to you.” I played the message and I looked at my wife and said, “Oh, she’s probably calling to get some suggestions from me about who could be the next one.” And my wife said “Don’t be an idiot, she’s calling to see if YOU would be…” And I said, “What? That is impossible. Why would they ask me? I can’t do that. I can’t lead things, or schmooze people, or be someone who runs a board meeting.” I didn’t even know what being a Chairman really meant. I figured it was fundraising, and talking to people, and I’m a terrible choice for that. But then, it turned out Ayelet was right. That was what they wanted. And every fiber of my being wanted to say no, I just want to stay in my room, write my books, be with my family. But I love MacDowell, and I had gotten so much benefit from MacDowell, my work had benefited so much from my time at MacDowell. I felt like if they thought I could do it, I would just have to take their word for it.

The capacity to detach yourself, to punish another person and to see them as less than you, less than human, is harder to do if you’ve been exposed to literature.

EB: I recently spoke with Deborah Eisenberg about the advice writers need but don’t often hear. She said writing is both embarrassing and takes a long time (which is part of what makes it so embarrassing). I wonder, what is the one piece of writing advice you think new writers need but don’t often hear?

MC: Well, the thing about it taking a long time, that’s definitely true for me. People say, “How long did it take you to write a book?” And I’ll say three or four years. And they’re always like, “What?!” And then I see it from their point of view, and that does sound like a long time. It feels like a long time. But that’s how long it takes! Like waiting for the wine you’ve made to be ready to drink. It’s just part of the process. I don’t think vintners hear as much of people saying, “Whoa, it takes eight years for it to be ready?”

I used to always have the same sort of pretty “blah” pieces of advice: “Read a lot.” Just the usual kind of things. And those are all still true, but there’s one now that I’m more aware of. And it’s advice I give to myself, as much as to anyone, but especially to younger writers. Writers coming up now. Which is put your — put this [points to phone] — away. When you’re out in the world, when you’re walking down the street, when you’re on the subway, when you’re riding in the back of a car, when you’re doing all those everyday things that are so tedious, where this [phone] is such a godsend in so many ways. As in that David Foster Wallace graduation speech, when he talks about standing in line at the grocery store. When you’re in those moments where this [phone] is so seductive, and it works! It’s so brilliant at giving you something to do. I mean walking down the street looking at your phone — that’s pretty excessive. But in other circumstances where it feels natural, that’s when you need to put this [phone] away. Because using your eyes, to take in your immediate surroundings… Your visual and auditory experience of the world, eavesdropping on conversations, watching people interact, noticing weird shit out the window of a moving car, all those things are so deeply necessary to getting your work done every day. When I’m working on a regular work schedule, which is most of the time, and I’m really engaged in whatever it is I’m working on, there’s a part of my brain that is always alert to mining what can be mined from that immediate everyday experience. I don’t even know I’m doing it, but I’ll see something, like,“That name on that sign is the perfect last name for this character!” Or the thing I just overheard that woman saying, is exactly the line of dialog I need for whatever I’m doing. And if you’re like this [phone in your face], you miss it all. Leaving aside the whole issue of screens being such time-sucks, how when you’re at your desk your computer is sucking your writing time, because we all know that. We all fight against that. It’s when you’re in those tedious, boring, everyday situations where it’s so seductive and so easy to get your email done, or message with somebody. Just put that phone away, and be where you are. That’s my advice.

Is Slow Communication the Future?

EB: Just to push that advice a little further: If I’m on the subway, I may not be on Twitter but I’m usually reading a book. Of course, I want to say that’s different, but is it? How?

MC: I think reading a book is different, because you’re very close to what’s around you still. You can hear it, your eye can drift off the page for a moment and you might see something and then go back to what you’re reading. But there’s something so riveting and all-consuming about your phone. As soon as you get into one of those moments where your attention might dip, if you’re reading a book, you look up, take a look around you. But on your phone, if your attention dips, you just swipe to a different app. Instagram. Now email. Your phone is always there with something new for you. A great book is an immersive experience but your environment can still intrude in useful ways.

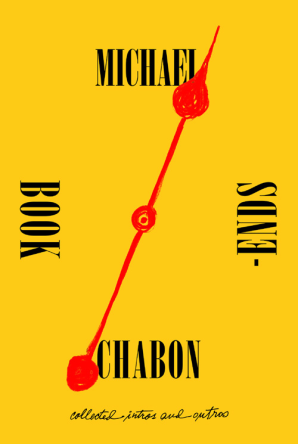

EB: Okay, final question. You’ve just put out Bookends, this compilation of your thoughts on literature from some introductions and afterwords you’ve written for other authors’ work. I loved it. There was something very energizing about discovering these books, films, and artists through your enthusiasm for their work. So this project was for me about discovery, because now I have a list of people I very eagerly want to read. I wonder, where are you going to discover new work now? How do you discover new language, new literature?

MC: The most reliable way is the same as it’s always been: through other writers. Things you read lead to other things. You’re reading an essay by Flannery O’Connor and she talks about, I don’t know, some Catholic American writer that you’ve never heard of. For me, it’s almost always been about writers leading me to other writers. In Bookends I talk about Susan Sontag’s intro to Roland Barthes. I had a real thing for Sontag when I was in my early twenties, and here she was going on and on about Roland Barthes. So then I went to check out Roland Barthes, because she’s a passionate recommender. Then there are recommendations that come from people around you. And then finally, I make these accidental, fortuitous discoveries. I’ll just stumble on something, or a new edition comes out of some forgotten book you’ve never heard of. That’s why I think it’s still so important to go into bookstores. That’s where I’ll discover that some publisher just brought out a reprint of some amazing looking book, and I’ll wonder, “How did I never hear of this writer before? This seems so perfect for me!”

Right now I’m reading William Blake and the Age of Revolution by J. Bronowski, which was just lying on a table at, I think I got it at Mo’s, in Berkeley. It’s used. I’ve never heard of it — the cover just caught my eye right away. I like William Blake, and I’ve never heard of this book before, and I love the cover, so…. And it turns out, it’s so incredibly well-written. The opening paragraph I’ve reread about twenty-five times, now, because it’s so magnificently written. And that happened, I made a new friend of this book, just by going into a bookstore. In a way it’s analogous to what I was talking about with the phone. Sure, you could go online and buy books. And you can “browse” that way, and it kind of works, but it’s not like those chance discoveries, where something just catches your eye like that. The book was orange. It was very 1970s. And then that typeface.

EB: I love it. I mean, who is J. Bronowski? I’ve never heard of him.

MC: He was apparently a mathematician, and he was also sort of a literary amateur. I think it was published in 1965, and this edition came out in 1970. And, as I mentioned before, in it he’s made reference to a couple of other English poets that maybe I’ve kind of heard of a little bit over the years, but I’ve never really checked out their work. Lesser-known English poets from the same time as Blake. And now Bronowski’s making me want to go check out their work.

Michael Chabon’s Advice to Young Writers: Put Away Your Phone was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Michael Chabon’s Advice to Young Writers: Put Away Your Phone