Shanthi Sekaran talks to the former editor of the Millions on the violent romance that accompanies nostalgia about the West

The miracles of creation are scant comfort when you’re rushing your kids to daycare and boarding a sluggish and sweaty BART, as Lydia Kiesling did a few Thursdays ago. She swept into Bica Coffeehouse in Oakland, and if this were a women’s magazine, I’d tell you what she was wearing. Let’s just say she was smiling, that she radiated warmth, that she looked glad to be out in the sunshine, glad to have arrived, glad to sit down with a cup of coffee.

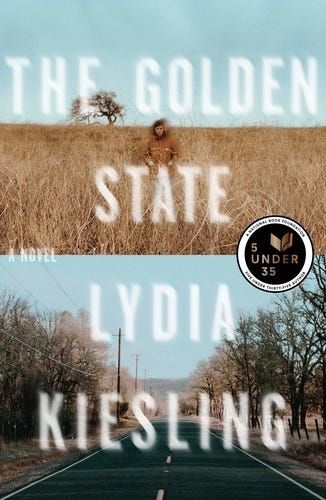

Though I’d never met Kiesling, I knew her work as editor of The Millions, and had been following the reviews of The Golden State, her debut novel about Daphne Nilson, a young mother in San Francisco whose Turkish husband is stuck abroad, trapped in an immigration nightmare. Fed up with the petty wranglings of her academic workplace, Daphne packs her car and her 18-month-old, Honey, and heads back her family’s home in the rural, forgotten reaches of northeastern California. What follows are days of disoriented single motherhood, as Daphne realizes that the classic road trip, the great American escape, isn’t quite the same with a toddler in tow.

I spoke with Lydia Kiesling about juggling writing and motherhood, the difference being an editor and a writer, and the danger of nostalgia.

Shanthi Sekaran: As editor of The Millions, you’ve been very engaged with the literary world, but this is your first novel. How is being a novelist new for you?

Lydia Kiesling: It feels very new and strange. The encouraging thing is that pretty much anyone writing a first novel is unprepared. There was that element of I don’t really know how this done and then — because I’d been writing about books and doing things like book reviews — I was like where do I get off doing this, after so long reading other books and being very picky about whether I liked them or not? Now I’m like wow, I was such an asshole. Writing a book is so hard.

SS: So how did this novel come into being? How was it born?

LK: I wrote other things for years. I started writing in 2009 and I’d say probably around like 2014, I let myself fantasize that writing a book would be possible. What had been daunting about it was one, just the finances. How do you just not work and write a book? And the second thing was, I think for any writer, especially if you don’t go to an MFA program — well actually I know a lot of writers who go to MFA programs who don’t receive a lot of guidance on the career stuff, on how to become a writer, how to build a career. It’s astonishing to me that that is not something that is provided. So the mechanics of how you would be a novelist seemed very opaque.

I think what really spurred the novel was when I had my first daughter, I started wanting to write things for that experience that I didn’t necessarily have a vessel for. All the book reviews I’ve written are very personal, and they’re almost in some way an excuse for writing about some of the things I wanted to write about. So I first started writing these vignettes — it was a universe that I recognized, but I had taken some liberties with it. And then I was like, Okay, well I think this could be a book. What would this as a book look like?

What had been daunting about writing a book was the finances. How do you just not work and write a book?

SS: I thought it was an interesting choice, and brave in some ways, to center motherhood in the way this book does, because it’s not just about the emotional journey of motherhood — that’s what most motherhood novels are about — but the endless, on-the-ground minutiae of motherhood. Can you talk about deciding to center motherhood in this way?

LK: Part of it is a form of narcissism, if you think you’re the star of your own movie that is your life. You know, those things, they can seem like such big struggles, and you can talk about them because you know that they’re just the most mundane things that people are dealing with, with small children, at all times, and it’s not that big of a deal. But it’s also, like, why does it fill you with such rage, or futility? And there’s something funny to me about having these epic dramas happen all the time, and there’s no descriptions of them out there, or place to put them. So in one sense, I was honoring that struggle, but then also, one thing that really strikes me, when I talk to women and men who have children, is the specificity of knowledge you have about your children, and how to make the day work. It’s this wealth of knowledge, but it’ll just go away. It’s this expertise that parents have in that moment of parenthood, and then it goes away. So I was describing that, putting it on the page and showing, for better or worse, what it really is. And I knew it was going to be sort of tedious to read about some of those things, but it’s also a tedium that people are living every single day, and why do we not have a little taste of that in fiction? Especially now that people are talking about auto-fiction and writing personal experiences. That’s a very personal experience, and I wanted to document that.

SS: So you saw the parenting material as possibly tedious, but decided to put it in there anyway. Can you talk a little about what we, as writers, ask of our readers? How do you, as writer, make the decision to include material that a hypothetical reader might find “tedious”?

LK: I think books have hugely important jobs to do in societies — both contemporary and future societies — as a means for communicating ideas and information about places and cultures and aesthetic fashions and modes of being. But as a reader I still count on them, in my heart of hearts, for providing joy and escape. And it was hard to reconcile a lot of what I found myself putting in my book, things that felt like important information about a particular person’s experience of motherhood at a particular moment in time, with my sense that books should be fun and enjoyable for readers. I was constantly living in that tension. So I thought about books I love that have sort of long languorous bits that feel necessary and important, even though I personally find those parts slightly boring. I don’t think I solved the problem so much as learned how to ignore it to a certain extent while I was writing!

SS: Going the opposite way, you wrote about stuff that wasn’t in your experience, like being married to a Turkish man, as Daphne is; having an international marriage, a cross-cultural marriage. You said you were a little hesitant about trying to do that. I had to do that, big time, in Lucky Boy, so I’m always interested in hearing about how other writers take on stories outside of their own experiences.

LK: There are so many conversations about what is and is not allowed. Things are allowed constantly. If you’re a writer who cares about doing a good job, it should be okay — with some trepidation — to really just write about anything that you haven’t done. And it’s not to say that you can’t find it within yourself to imagine it, but you know, writing about a place that you haven’t been, it’s weird to do that. And it should feel weird. So first I tried to avoid the problem almost by saying, He’ll be just like my husband I have now, except he’ll be from Denmark! And that was just really silly.

Then I started thinking, Well why not write about someplace you did live, and — at one time, at least — spoke the language? Why not just do that? And I’m still not settled that it’s correct, but I can say that I honestly used what I had experienced and seen (in Turkey) to the best of my ability, and that in the world I made in the book, it checked out. I had a friend who was Turkish read some parts, especially things with class. Like, in America, if someone told you what college they went to, you could immediately make some assumption about what their background is. And those are the types of things where you could live somewhere for decades and never necessarily know. And so initially, Engin went to a university and I asked her, “Do you think this university makes sense?” And she was like, “No, from what you described, I think it would make more sense if he went to this school.” It was such a small detail in the book, but it meant a lot to me. I used what I had and tried to be very conscientious in asking Is this something I saw? When I described what a family was like, Is this a family I might have met? And then I found someone whose opinion and judgement I trusted to read over some stuff to, you know, make sure my (Turkish) grammar wasn’t messed up.

And then in terms of the marriage stuff, I think marriages that are based on love and affection have a sort of through line. My husband was like, “I noticed that you wrote me out of this,” and I was like, “No I didn’t! Where do you think the ideas I have about the culture of family and how you feel about someone come from? I get those from you.” So, he’s in there. Just sublimated.

Books have hugely important jobs to do in societies — both contemporary and future societies — as a means for communicating ideas and information about places and cultures and aesthetic fashions and modes of being.

SS: The memories that Daphne has about Turkey are so beautiful and so beautifully told. Did those come from your own nostalgia?

LK: Definitely. Turkey invites so much “East meets West” romanticizing and Orientalizing, so on the one hand, I’d be writing about the Bosphorous and thinking, “Ugh, this sucks,” but actually, the Turks I know feel the same way — especially about Istanbul. I’ve never met a person who’s been there who isn’t like, This is such a special place, and I think it’s okay to say that some places are special. So that’s one thing I sort of struggled with. There weren’t that many times when I had to tone down the romanticizing but there’s something wistful about the book, I think, because even though Daphne’s life just seems so difficult to me, I admire her, because she made a choice, whether she thought of it as a choice or not, that was different from what I would have done.

When I was in Turkey, I came back to California because I needed to be closer to my mom and my grandparents. I didn’t have the courage to live somewhere completely different from where my family and friends lived. I mean, there are lots of terrible people who expatriate all the time, and there’s no need to admire them, but there is something very brave and interesting about someone who says, Oh I’m just going to marry someone whom I have no cultural affinity at all with. Those couples are always interesting to me. And I think a lot of people in those couples would laugh at this idea that there’s curiosity or romance about it, because they’re like Oh, I love this guy, and we now live together.

SS: Going back to the chapters with Honey, I laughed out loud many times. The church scene, for example, was hilarious. There were sections where you’d run through everything Daphne does in the morning — it was this endless, breathless list, more things than most people do in an entire day, and then Daphne says, “It’s 8:15 a.m.” I was like Oh my god, those endless days with a toddler. Can you talk about the book’s humor?

LK: Humor is very much a part of my sensibility. It’s a coping mechanism and also a defense. And so I wanted to have a little bit of slapstick in there, but I worried at the same time that It would be a Trainwreck thing of quirky white woman being funny about their own foibles and there is something revolutionary about that in some small instances, but it can be too much. So at some point, I was like, Am I being too ‘funny’ about this? But it’s part of my parental coping. I can get very wrapped up and in despair about a power struggle with a toddler, but when I’m being my best parenting self is when I feel like I can see the humor as it’s happening. And so, even though, you know, the child is barfing, you’re just like This is funny, you’re little, you don’t know what you’re doing, and I’m beside myself. Let’s laugh. I’m already asking the reader to do a lot in the book, and so some humor — assuming the reader shares my sense of humor — felt kind of necessary, to bring some levity.

I knew that our immigration system was messed up, but I was not expecting, when I wrote this book [during the Obama administration], that we would have just the pure violence that is still happening now.

SS: Who was your favorite character to write?

LK: Daphne’s obviously the closest to me, and I actually got sick of her. I was already in my own head, and she was just the worse, more stressed version of myself.

I actually had a huge amount of anxiety about Alice [an elderly woman who befriends Honey and Daphne], because Alice is based on a real person. The book is dedicated to Phyllis Hodgson and she was this woman married to a scholar of Islamic Studies named Marshall Hodgson, who wrote The Venture of Islam. He died in 1968 and is very famous in this very limited Islamic Studies context in America, and so I wrote my MA thesis about him. And so I got kind of obsessed with him. He also had a very tragic personal life. He had three children and all of them died young, and two of them were born with a terrible neurological illness. So I kept thinking as I was reading all this, What about his wife? I would ask all these academics, “What happened to his wife?” and they’d be like “Hmmm, I don’t know.” And then I found out that she was alive, and I met her, and she lived in Wisconsin. She was in a facility, a lovely place in rural Wisconsin, but it wasn’t her family who was caring for her. It was friends and neighbors who had known her for years and loved her, and so I met with them, and met her, and somehow she just got into the book. But I was like, This person is alive, she never did any of these things [that Alice does]. It’s not her, but clearly anyone who knows her would be like, This is her. So for a while, I was thrashing around about that and was really asking myself, Well what is fiction, what’s okay and what’s not okay?

She passed away — not conveniently — but it did make some things slightly less anxious, because she’s with the universe now. I initially had more of her, a first person from her perspective, but because I had this anxiety, I didn’t commit and I didn’t go hard enough. I was hedging about it, which was very weird and impersonal, and so Claudia, my agent was like “Everything’s working for me except that. Take those parts out.” And it was so easy to do it, that it was so obvious (the Alice sections) didn’t belong. They were like a weird tumor hanging off the book. It got snipped.

SS: Poor Alice.

LK: Yeah, and you’re not supposed to read your Goodreads reviews, but I did read a Goodreads review that referred to her in a way I just love. It was like “You get a glimpse of her that reveals a whole other picture, like the moon, when you see just a sliver of the moon.” So I was like, I can be satisfied with that. And then actually, I got an email from someone who had cared for her, and they were like, “You really got her.” That’s the email that’s meant the most to me. So, I was the most fascinated with her, but there was a lot hesitation mixed up in it.

SS: So they knew Alice was Phyllis Hodgson without you telling them? They could just see it?

LK: Yeah, and I think people were generally confused, because I was doing this almost investigatory work to track her down and speak with people who’d known her, because I was doing this simultaneously to starting the book, and I wasn’t sure they were going to be the same project, but it was important for me to know as much about her as I could know about her husband. So people go the sense that I’d be working on some article about her. One professor I talked to was like, “So, you didn’t write the book about the Hodgsons?” I was like, Well, it’s in a different — I made a U-turn. But she’s still very much there. And some of the things Alice says — I can’t really overstate how difficult this woman’s life was, and there are a lot of people who have terrible things that they’re just living with, and just walking around among us, and it’s amazing that they’re able to do anything. It really stuck with me. One of the things she said when I met her was “I had babies and it railroaded my life.”

SS: I mean, that’s kind of what this book is about. Being railroaded by babies. What is it like for you being a mother and a writer. How have you negotiated that?

LK: Well I’m really glad you asked that, because with the writing thing, the questions seems critical, because writing is so non-remunerative, so what do you do about the finances? And it turns into sort of a Marxist view of parenting. I mean, I do believe that I owe this book entirely to having my first child. Part of it is coincidence. Just like with any other job, years where you’re advancing in your career coincide with the years you’re having kids, if you’re having them. But, I think there’s an urgency (my first child) gave me, a sense that I’m feeling so many different things. My tolerance for everything has changed. How do I need to rearrange my life to make it more tolerable to me?

I do know there are people who write like, during nap times, and they don’t have dedicated childcare.

You always hear about people just really making it work with ridiculously difficult situations, “On Monday I have half an hour, On Tuesday I have two hours.” People are really making it work. I think that is wonderful. I think I am not able to do that. I need writing to be a job the same way another job would be.

Lydia Kiesling’s Favorite Books That Aren’t By Men

SS: The playwright Andrea Dunbar used to lock her children in their bedroom so she could write.

LK: I think having two children has made it slightly complicated, but I have no regrets. I’m going to make it work. I might just have to adjust my expectations of what is realistic in terms of output and time and how long it might take me to write another book.

SS: Speaking of which, you wrote this book during the Obama administration. I feel like every book, when it comes out into the world, starts a conversation with the world it’s in. Can you talk about the conversation The Golden State is having with our country now?

LK: Well, the sort of obvious way is through immigration. The green card fuckery that happens in the book is based on real fuckery that I have known, that people I know have experienced, but then once you talk to anyone about it, it’s just like story after story after story and the people I end up talking to are, like myself, educated, and they have all the resources and wherewithal to navigate the system, and still it is absolutely opaque and difficult. So that’s the main thing. I knew that our immigration system was messed up, but I was not expecting, when I wrote this book, that we would have just the pure violence that is still happening.

I think of the Islamophobia aspect of the book, which took place in the summer of 2015. That was before San Bernardino and Bataclan, so it’s only going to get ramped up in the world of the book. In terms of the world stage, the book is not hopeful. I think there is individual hope that happens, but it’s also before the attempted coup in Turkey. So the conversation it’s having with the world right now is like Well, things don’t seem great.

Sometimes when I was writing I was like this is how a person on the left would describe, disdainfully, people in small towns who have conservative politics. But just like with everything else in the book, I did a lot of fact checking and reading of letters to editors of newspapers. I’m on a mailing list for the State of Jefferson, so I read those things, and that’s reflected in the book. Since it came out, people have written me who live in the country where the is based, and they’re like “I run a progressive place.” There’s a lot happening. I think it’ll continue to change. There are other kinds of stories that can be told about rural California that are not just like We’re mad. But We’re mad is definitely part of the equation.

SS: We’re mad, but also there are individuals who move through those spaces the way Daphne does. The world isn’t great, but here’s a woman and her baby, down on ground-level.

LK: Yeah, and I wish there was a way we could separate the decline paradigm that wasn’t just they’re mad and they’re Republicans. When my mom goes up to her hometown, it’s sad for her, because it’s not the same place. You can acknowledge that and be sad about it and be careful not to just fall into nostalgia for this imagined, great time that existed in the 50s when everyone was happy, because we know that’s not true. But there are people who justifiably feel like things have changed for the worse.

There’s a lot of romance wrapped up in this nostalgia, but a lot of that is violent, harmful romance. It’s about the subjugation and murder of indigenous people. The cowboy myth. That’s what [the West is] built on.

SS: I see a parallel between that small town nostalgia and the nostalgia Daphne feels for Turkey. And yet she’s stuck in the small-town nostalgia.

LK: White people love to be like Here’s my ancestry, in a really stupid way, where it’s just like no, no one cares about your German great-great grandfather. That’s not a thing. But there is this feeling: People like to have roots somewhere, and feel like this is my place. Like Daphne. There’s a lot of romance wrapped up in this nostalgia, but a lot of that is violent, harmful romance, like with any place. It’s about the subjugation and murder of indigenous people. The cowboy myth. That’s what [the West is] built on. So there’s the moral underpinnings of that. But there’s also the I like to have nice restaurants near me and many conveniences open late, and I don’t want to live in a very small town. So it’s kind of like, Okay, you want roots? Here they are.

About the Author

Lydia Kiesling is the author of The Golden State and a 2018 National Book Foundation “5 under 35” honoree. She is the editor of The Millions and her writing has appeared at outlets including The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker online, The Guardian, and Slate. She lives in San Francisco with her family.

About the Interviewer

Shanthi Sekaran is a writer and educator from Berkeley, California. Her recent novel, Lucky Boy (Putnam/Penguin), was named an IndieNext Great Read, and an NPR Best Book of 2017. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times, Salon.com, Canteen Magazine and Huffington Post. She teaches creative writing in the SF Bay Area and has two sons.

Lydia Kiesling’s ‘The Golden State’ Tackles the Hardships of Motherhood and Immigration was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Lydia Kiesling’s ‘The Golden State’ Tackles the Hardships of Motherhood and Immigration