The invention of “bookishness,” and why Marie Kondo is so threatening to people who buy in

D o you remember, back in 2017, when reversing your books for aesthetic appeal was briefly a thing? Apartment Therapy posted a photo to Instagram of a bookshelf with the spines facing inward, and the dramatic response — dozens of users denouncing the trend as anti-intellectual, even comparing it to book-burning — felt, at the time, like the ultimate example of the bookish Internet’s capacity for outrage. Then Marie Kondo came for our books, and the bookish Internet proved me wrong.

Marie Kondo, for the uninitiated, is a Japanese organization expert who was catapulted to fame in 2011 when her book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, became an international bestseller. The book advocates for the KonMari method, in which people declutter their homes by piling all of their worldly possessions together and asking of each one whether it “sparks joy.” (We’re going to talk about joy in a minute, hold on.) In 2019 Kondo was further elevated from book-famous to Netflix-famous with the release of Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, an eight-episode reality series in which Kondo walks clients through KonMari-ing their homes. As a result, your local thrift shop was quickly saturated with other people’s un-joy-sparking possessions, and the Internet suddenly had a lot of opinions about clutter.

In particular, a number of white women came to the defense of clutter in general, and books in particular, in language that was, frankly, pretty racist. Feminist writer Barbara Ehrenreich tweeted (and then deleted) a claim that Kondo’s accented English signaled the fall of American dominance, and then followed up with a tweet that is not much better: “I confess: I hate Marie Kondo because, aesthetically speaking, I’m on the side of clutter. As for her language: It’s OK with me that she doesn’t speak English to her huge American audience but it does suggest that America is in decline as a superpower.”

Ehrenreich’s focus on the aesthetics of clutter seemed to be a dog-whistle, prompting similarly racializing and xenophobic comments from American poet Katha Pollitt, who referred to Kondo’s “fairy-like delicacy and charm,” and Elaine Showalter, who in a now-deleted tweet claimed that “She is certainly a pretty little pixie … but I am immune to Tinkerbell teaching me how to fold my socks.” But if there was one thing about Kondo that really got the collective bookish internet’s goat, it was her suggestion, in episode 5, that people should get rid of books that do not spark joy.

She might as well have suggested that people shelve their books backwards for the haste with which her tidying suggestions were equated with book burning. The point of books, readers raged, was not joy. As Canadian author Anakana Schofield wrote in The Guardian: “The metric of objects only ‘sparking joy’ is deeply problematic when applied to books… Literature does not exist only to provoke feelings of happiness or to placate us with its pleasure; art should also challenge and perturb us.”

If there was one thing about Kondo that really got the collective bookish internet’s goat, it was her suggestion that people should get rid of books that do not spark joy. The point of books, readers raged, was not joy.

The racialized language in Ehrenreich and Pollitt and Showalter’s defenses of clutter carries through in Schofield’s defense of the unedited personal library. She refers to Kondo tapping books “with fairy finger motions” as part of “the woo-woo, nonsense territory we are in.” The heart of Schofield’s critique appears to be a fundamental misinterpretation of what Kondo means by joy, a misinterpretation that Ellen Oh, founder of We Need Diverse Books, calls deliberate:

There is an overemphasis on the words ‘spark joy’ without understanding what [Kondo] really means by it. Tokimeki doesn’t actually mean joy. It means throb, excitement, palpitation. Just this basic understanding annihilates Schofield’s argument that books should not only spark joy but challenge and perturb us. Tokimeki would imply that if a book that challenges and perturbs us also gives us a positive reaction, then why wouldn’t you keep it?

What about Kondo’s advice — that people should consider getting rid of some of their books, if those books have become stress-inducing clutter — is so profoundly threatening that white feminists across social media have been led to produce such very bad takes? It has something to do with the special status that self-identified book lovers attribute to books, and the corresponding outrage they feel when someone like Kondo suggests that they might be objects on par with underwear and coasters. To return to Schofield’s anger, the issue isn’t that Kondo has entered “woo-woo, nonsense territory,” but that her nonsense takes a different shape than Schofield’s own: Kondo awakens books by tapping them with her fingers, whereas, writes Schofield, “Surely the way to wake up any book is to open it up and read it aloud.” Why is it nonsense to tap books, but not nonsense to treat them like grimoires waiting to be activated?

We could pull apart the xenophobia, racism, orientalism, and classism at work in these critiques all day, but I want to focus on how self-identified bookish people reacted to the association of books with clutter, the demotion of these objects from sacred to banal — or, maybe more accurately, the insistence that they are no more sacred than any other objects. Here’s an exchange that I would characterize as both typical and illuminating:

@MidianiteManna Ok. They’re still just objects.

— @brennacgray

@brennacgray Ah. No, to me they are experiences. It’s like saying a trip to Paris is an object.

— @MidianiteManna

@MidianiteManna Ok.

— @brennacgray

In addition to marveling at the Twitter-beef-defusing skills of popular culture scholar Brenna Clarke Gray, let’s think about what it means to call a book an “experience.” The status of the book as object is at once denied and overburdened: the physical codex is both a stand-in for the act of reading and a trophy to demonstrate that you have the correct emotional and intellectual relationship to that act. Mere book-owners may see books as things that can be repurposed as decor or given away when they’re no longer needed, but readers know that books contain other worlds — and their book collections become status symbols, signs of their heightened sensitivity.

There is nothing new in this link between loving books and conspicuously consuming them. There is a long, classed history of book consumption as social posturing. As American culture scholar Lisa Nakamura points out, displaying books for others to view has long been “a form of public consumption that produces and publicizes a reading self.” But contemporary bookish culture extends conspicuous consumption beyond books themselves, to a range of lifestyle goods that have, in fact, played a significant role in the recent revival of independent bookstores (and in the expansion of Canadian book retailer Indigo into the U.S.). It is also more complex than a simple display of cultural or institutional capital, rooted as this culture is in a deep emotional investment in books that consumers have been taught to express through consumption. And we can see it playing out through the history of book-buying, from early bibliophilia to the midcentury Book-of-the-Month Club’s offer to help you build a personal library to millennial-aimed blogs that turn bookishness into consumer behavior. Understanding something more about the evolution of bookishness, I think, helps us understand what happened when Marie Kondo came for our bookish clutter.

There is nothing new in this link between loving books and conspicuously consuming them. There is a long, classed history of book consumption as social posturing.

In Loving Literature: A Cultural History, Deirdre Lynch traces the long history of book obsession, or bibliomania, back to the Stoic philosophers’ anxieties about unseemly attachments to books. In the late 18th century, however, the industrialization of paper production and then print created a newly robust book market that was actively invested in anthropomorphizing books, making them part of “the living world” so that people could love them (by buying them). Stoic arguments against the luxurious over-consumption of books were, as Lynch writes, “patently trickier to sustain in a culture that was … figuring out ways to vindicate consumerist passions.” Alongside these consumerist passions for books came the transformation of the domestic sphere, with “the previously commercial, quasi-public space of the house [becoming] a personal sanctuary” — and reading becoming an increasingly private activity, one that the middle-class gentleman performed in the comfort of his own home, drawing on the reserves of his own library.

Note the specificity of gender here. The bibliophile was a man, and he collected books not indiscriminately but with great attention to their status, their value, and their collectibility. But, as Lynch points out, women were still engaging with book culture, just not via consumer decisions. (Women would become increasingly responsible for domestic consumption decisions in the 20th century, which is when the book market begins to swing decisively towards the female readers). So what form did women’s bibliomania take? Lynch describes a kind of literary scrapbooking effort that bears a striking resemblance to contemporary fan fiction and fan art worlds:

The homemade manuscript anthology — a compilation of original poetry and prose mixed with hand-copies extracts from published sources sometimes augmented with clippings from newspapers and periodicals; amateur watercolor landscapes (sometimes souvenirs of travels); imaginary portraits of characters from novels or poems (especially Walter Scott’s); pastel pictures on rice paper achieving a tremendous level of zoological/botanical accuracy of sea shells, butterflies, and/or flowers; various other specimens of fashionable feminine accomplishments, decoupage and flower and fern pressing included; locks of hair; memorial cards paying homage to the recently deceased.

Hold onto this contrast between a highly discriminating form of curated library collection and a highly personalized, almost fannish, engagement with books. The latter, I think, more accurately predicts the direction that bookish culture has gone in the 21st century, perhaps because book buying has become a predominantly feminized activity. (We also see the ongoing gendering of modes of engagement in the distinction between curative and transformative fandom.) But I don’t want to skip ahead.

It’s Okay to Give Up on Mediocre Books Because We’re All Going to Die

Nineteenth-century bibliomania paved the way for the 20th century middle class’s fixation on acquiring a proper library, as Janice Radway outlines in A Feeling For Books. Radway explains how the Book-of-the-Month Club (founded in 1926) became a prototype for the marrying of commerce and culture in American book culture. The organization took advantage of the expanding consumer power of Americans post-World War II, as well as the growth of the professional-managerial class, which she describes as “professionals and knowledge workers [who] were necessary to circulate the huge quantities of information so essential to an integrated consumer economy.” The children of the professional-managerial class were “taught to value books and to aspire to some form of intellectual work,” but the way they were taught to value books was oriented a little differently than the canon-conscious bibliophilia of the previous century. The Book-of-the-Month Club, Radway asserts, was invested in the idea of the “intelligent, general reader,” a readerly identity that she links to the increasing focus of the book market on marketing subcategories. Here’s Radway on how reading was understood by the Club:

An implicit theory of the practice of reading served as the foundation for the business of day-to-day evaluation at the Book-of-the-Month Club. Reading was not conceived as a unitary practice, nor were books evaluated according to a single set of criteria. Rather, reading was conceptualized as elaborated and wholly context-specific. Sometimes people read to be entertained; sometimes they read to be put to sleep; sometimes they read to find out how to eat; and sometimes they read to live other lives, to think other thoughts, and to feel more intensely. … To measure the success of any given book, the Book-of-the-Month Club editors evaluated not the features of the text alone but, rather, the precise nature of the fit between what the book offered and what its likely reader would demand of it.

This non-unity of reading makes sense as a marketing strategy, and is evident in the way the Book-of-the-Month Club framed its selections, bringing together classics, weighty nonfiction tomes, and light romantic fiction under the umbrella of a generally “improving” reading practice. The figure of the “intelligent, general reader” as free to read across categories is vital to the development of contemporary bookish culture; it lets the book market moralize reading and books in general while refusing genre- or book-specific snobbery. To be a reader is better than to not be a reader, but one kind of reading or book is not better than another. This kind of reading is what Radway defines as the middlebrow, and it has a lot to do with how books make us feel.

To be a reader is better than to not be a reader, but one kind of reading or book is not better than another.

In The New Literary Middlebrow, Beth Driscoll demonstrates that feelings are still the point for contemporary middlebrow readers. Driscoll attributes eight characteristics to the literary middlebrow: it is middle-class, reverential, commercial, mediated, feminized, recreational, earnest, and emotional. We can see, in this list, traces of how 18th- and 19th-century bibliophilia transformed into the middlebrow literary culture of the present day — the link between reading and middle-class domesticity, the attempt to rationalize a reverent relationship to commercial objects — and I think we can also see how the middlebrow picked up on those homemade manuscript anthologies, encouraging an emotional, feminized, and highly mediated relationship to books. All of these forces — class-consciousness, hyper-mediation, the link between reverence and commerce, the feminization of book consumption, and especially the figure of the general, or recreational, reader — come together in the figure of the 21st-century “bookish” individual.

So let’s talk about bookishness. The OED tells us that the word can be dated back to the 16th century, when it meant, unsurprisingly, “serious about reading books” or “studious.” Alongside those neutral definitions, though, there’s also a history of the term being somewhat pejorative, suggesting people who are unhealthily invested in books and thus divorced from the real world. The way bookishness gets used in contemporary book culture resembles nothing so much as a triumphant reclamation of the term, an insistence that over-investment in books could only ever be a good thing. BookRiot, an American new media company founded in 2011 as a lifestyle destination for book lovers, is a case study in the semantic slide of the term (though it’s only one example among many). To get a sense of how the word is being used, let’s look at a few posts.

The May 30, 2018 post “‘By Age 35’: Bookish Edition,” a play on the “by age 35” meme that was circulating at the time, tells us a lot about BookRiot’s idea of bookishness. The post is both self-consciously irreverent and illustrative. It focuses on conspicuous consumption — “you should have your spouse seriously look into shoring up the foundation under whatever room in which the majority of your books reside” — as well as the elevation of quantity over quality, suggesting you should have re-bought your childhood favorites, and filled your shelves with romance novels, “doorstopper history books,” and “an entire shelf of books you know for a fact you’ll never read, but you want people visiting your house to see that you own them.” The intermingling of romance, history, and classics on the same (over-burdened) bookshelf is reminiscent of the Book-of-the-Month Club’s intelligent general reader, who knows that it doesn’t matter what you read so long as you’re reading (or at least buying) a lot of books. A January 9, 2019 BookRiot post offers challenges for a “bookish bucket list,” including traveling to a bookish destination, meeting a favorite author, and spreading bookishness through your community “by helping someone else learn to love reading.” You can see the word sliding, from “really into books” into a kind of lifestyle or identity label, one in which “liking books a lot” (any kind of books!) can become one’s entire identity.

You can see the word sliding, from “really into books” into a kind of lifestyle or identity label, one in which “liking books a lot” (any kind of books!) can become one’s entire identity.

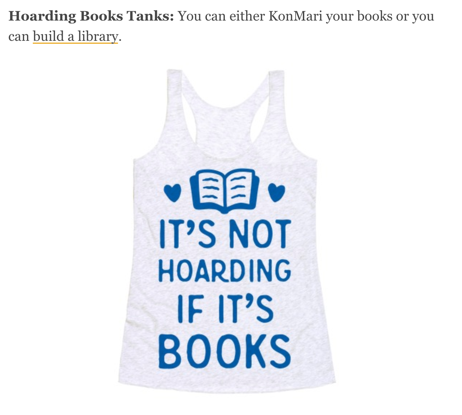

The most interesting manifestation of the bookish identity, for me, comes through in the feature “Book Fetish,” which is, as of my writing this, on its 343rd installment. Book Fetish is a testimony to the nigh-complete expansion of bookishness into a consumer category. It is, to be clear, not about books, but about book-proximate accessories likely to appeal to people (particularly women) who identify as bookish. A scan of a few recent columns gives a sense of the range of things: pencils, notepads, and bookmarks, sure, but also cross stitch patterns, enamel pins, tea pots, dish towels, t-shirts, mugs, jewelry, planters, art, and more and more and more.

And a major theme of these collected “fetishes” is that books are more than mere belongings — which brings us back to Marie Kondo and the belligerent rejection of her premise that books are just things. We might call it ironic that this column advertises non-book consumer items that themselves advertise the non-consumer-item status of books. Let me try to break that down: the special status of books, which we can link back to that 18th-century desire to anthropomorphize books in order to support a powerful new book market, is stamped all over Book Fetish. But the column itself testifies to the deep investment of bookish culture in the book market: it celebrates the conspicuous consumption not just of books, but of accessories that advertise your conspicuous consumption of books.

Nakamura, writing about the important role Goodreads plays in contemporary book culture, points out that the platform expands the commodification of books and readers:

Goodreads shows us how social networking about books has become a commodity, a business that lays claim to all user content, admits no liability, and reserves the right to terminate user profiles and data for any reason or no reason. Our carefully maintained Goodreads bookshelves, some of which contain thousands of books, can be abruptly disappeared.

The movement of book culture online — from buying books on Amazon to reading them on a Kindle and reviewing them on Goodreads — has far from curbed the commodification of the book world: instead, it has heightened to a degree those 18th-century bibliophiles could never have imagined. The incorporation of Goodreads into the Amazon megalith further exacerbates this situation, the special status of books somehow serving as a smokescreen for whatever Amazon is really up to (fun fact: googling “what is Amazon REALLY up to” yields 1.4 billion hits!). At the same time, this leakage of book fetishism beyond books themselves into the lifestyle accessories associated with bookishness has been a major factor behind both the survival of Canada’s bookstore chain Indigo — which recently expanded into the U.S. while rebranding as “the world’s first cultural department store” — and the resurgence of independent bookstores. Is it overkill to imagine the niche indie bookstore, with its combination of carefully curated books, quality scented candles, and ironic enamel pins, as a modern-day version of the homemade manuscript anthology — a curated space in which bibliophilia might flourish beyond the limits of books themselves?

Let’s end by bringing this full circle, back to the outrage so many (white) people directed toward Marie Kondo’s suggestion that books might be things like any others. The intensity with which self-identified book lovers love books is far from “natural”: it is instead the culmination of a complex set of cultural and economic transformations over the past 300 years that anthropomorphized books while simultaneously valorizing their consumption, that made book-loving into a consumer identity so well-defined that it has birthed a thousand cross stitch patterns. So well-defined that when threatened with a competing cultural understanding of what kinds of things books are, and how you might want to relate to them, many “bookish” folks completely lost their shit.

Liking Books Is Not a Personality was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Liking Books Is Not a Personality