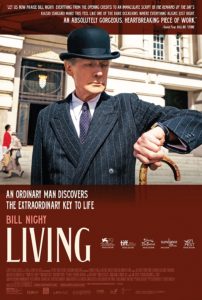

Kazuo Ishiguro has had a busy few months. The acclaimed novelist has been attending film festivals and walking red carpets to promote the film Living, for which he wrote the screenplay. Living—a remake of the 1952 Japanese film Ikiru, directed by Akira Kurosawa, which was inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 novella The Death of Ivan IIyich—is set in 1950s London and stars Bill Nighy as Rodney Williams, a senior bureaucrat in the Public Works department who is dying of cancer. The film has been an awards season darling, and this January Ishiguro was nominated for an Academy Award, his first, for best adapted screenplay.

No stranger to big awards, Ishiguro has won the Booker Prize, the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in 2019 received a knighthood for his contribution to literature. His novels include 1989’s The Remains of the Day, a slim tour de force about a loyal English butler, which was made into an Academy Award-winning movie with Anthony Hopkins, and 2021’s Klara and the Sun, about a solar-powered Artificial Friend that’s given as a companion to a lonely child (think of the AF as a more benevolent version of the robot in M3GAN).

No stranger to big awards, Ishiguro has won the Booker Prize, the Nobel Prize for Literature, and in 2019 received a knighthood for his contribution to literature. His novels include 1989’s The Remains of the Day, a slim tour de force about a loyal English butler, which was made into an Academy Award-winning movie with Anthony Hopkins, and 2021’s Klara and the Sun, about a solar-powered Artificial Friend that’s given as a companion to a lonely child (think of the AF as a more benevolent version of the robot in M3GAN).

Ishiguro joined me via Zoom from his home in London to talk about living to the fullest, making art out of office bureaucracy, and preparing an Oscars speech.

Elaine Szewczyk: Living is an adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru. Why did you want to write it?

Kazuo Ishiguro: I’ve been wanting somebody to remake Ikiru for a long time. I always thought it would work really well if you transferred that material into an English postwar setting. That English postwar setting was kind of the last generation of English gentlemen. I’m not saying English gentlemen have died out completely, but that era was the last time when males of a certain age all thought they had to conform to a certain kind of behavior, uniform, and manner, and certain people of that class, they were like Mr. Williams in Living. I saw the tail end of that when I was growing up in England, and I’ve always been fascinated by that kind of England, and what drove people to be the way they were.

ES: Have you always been a Kurosawa fan?

KI: Yes, and Ikiru had a profound impact on me. I grew up as a teenager and a student thinking about that film, it’s message. It meant a lot to me at that age, when you’re trying to figure out what’s the meaning of life. How do you lead a meaningful life? Especially if it doesn’t seem realistic as it didn’t at that point in my existence, that I’d have anything other than a fairly straightforward humble middle class life, working in some office somewhere.

ES: The film is a meditation on life, death, and mortality. What about these themes interests you?

KI: For me, that diagnosis of terminal illness in Living is like a MacGuffin. It’s a device for triggering this question: When you know you’re life is short, when you really have to think about your life, what matters to you? Are you happy to say that you just existed? You hung around and you died, or do you want it to be something more? Although Living is ostensibly a story about a guy who’s dying of cancer, the focus is somewhere else. It’s about, How do you live? What does it mean to live to the full?

ES: The protagonist of Living works in a government office marred in bureaucracy. He’s a paper pusher surrounded by paper pushers. The office scenes are slyly witty. How does bureaucracy illuminate the human condition?

KI: Bureaucracy is not usually seen as a commercial selling point in a movie. This movie we’re making, it’s going to be set in an office, with lots of piles of paper! Office work is a kind of metaphor. Offices easily lend themselves to metaphor because you’re seeing in some sort of concrete form the way life is compartmentalized and people are squashed into these existences where they’re given this overwhelming routine of work. And it’s difficult for them to see from cubical to cubical how they relate to each other, never mind how their contribution relates to the outside world and to the human enterprise in general.

ES: In those office scenes, the stacks of papers, the unprocessed documents that sit on workers’ desks, seem to always be precariously teetering and getting higher and higher. It makes for a powerful visual.

KI: It’s interesting, today, to look at a pre-digital workplace, so you can see the physical stacks of papers that are overwhelming people. In a way, digitization has allowed us to disguise a lot of that, the futility of a lot of the stuff that’s going on. More than ever we’re in workplaces that are hard for us to identify in terms of their meaningfulness. Even if we think we’re part of some larger corporation that’s doing something useful in the world, it’s difficult to figure out how your particular little contribution is important.

ES: How is writing scripts and books different?

KI: Over the decades I’ve learned a huge amount about writing novels. I feel like I’m just learning on the job about screenplays. One key difference is that a screenplay is a contribution to something that a team is going to work on, so it’s necessarily a collaborative document. If the screenplay is working then everything harmonizes. If the screenplay is weak it doesn’t matter how brilliantly other people do their work, the screenplay will always betray the final product.

ES: Where were you when you heard you’d been nominated for an Oscar?

KI: My wife and I were in the kitchen. I completely blew it actually. I had arranged a three-hour script meeting for the same day. I’d just managed to get the announcement, I was looking over my wife’s shoulder as she was watching on her iPad, then I had to leave the house. But it was fantastic, a terrific honor. There are some very talented people who’ve worked decades in the film industry and have done far more than I have and have never received a nomination. So a part of me feels some imposter syndrome.

ES: What was the script meeting about?

KI: I was meeting with Guillermo del Toro to discuss a future project of ours. We were with a couple of other people. We booked a room in a hotel and were having a fairly intense discussion and that’s what we were doing instead of celebrating.

ES: What’s the project you’re working on with del Toro?

KI: It’s an adaptation of my novel The Buried Giant. The success Guillermo has had with his film Pinocchio has encouraged him in his conviction that this is a really interesting moment for stop-motion animated films. We’ve been thinking about an animated version of The Buried Giant for years. I haven’t been speaking about it but I’ve noticed that Guillermo has so I guess I’m allowed to talk to you about it. He’s got a live-action film he’s about to shoot here in Britain, but he said The Buried Giant will be his next animated film.

KI: It’s an adaptation of my novel The Buried Giant. The success Guillermo has had with his film Pinocchio has encouraged him in his conviction that this is a really interesting moment for stop-motion animated films. We’ve been thinking about an animated version of The Buried Giant for years. I haven’t been speaking about it but I’ve noticed that Guillermo has so I guess I’m allowed to talk to you about it. He’s got a live-action film he’s about to shoot here in Britain, but he said The Buried Giant will be his next animated film.

ES: The Buried Giant is a fantastical novel about memory loss, set in a post-Arthurian England. It seems like a perfect del Toro project. Will you write the script?

KI: No, Dennis Kelly will. He wrote Matilda the Musical. I prefer to stay away from adaptations of my own books. After a certain point I don’t think it’s healthy if I’m lurking about like some kind of weird ghost from the past.

ES: What are your feelings about adaptations?

KI: I’m developing fairly strong views about adaption, especially now that I’ve adapted the Kurosawa movie myself. I believe in adaptation. It’s part of that great tradition that we’ve always had as human beings, telling stories then passing them on. Stories gain a mythic fairy-tale status when they start getting changed a little bit. Different generations bring something different to it. Today part of that process has become accelerated. Books get turned into films, films get turned into TV series. It’s a fascinating process and some authors of books resist that instinctively and I’m sympathetic to that. You’ve written a book and you don’t want it changed, but, personally, I feel it’s an honor.

ES: You’re headed to the Oscars in March. Will you prepare a speech?

KI: Ever since I’ve been about 30 I’ve been dragged along to awards ceremonies, where I didn’t know whether I’d won or not. A lot of the ceremonies have this feature where the nominated people, the shortlisted people, don’t know if they’ve won. You just sit there. And I’ve become used to the psychology of this and I think I’ve kind of gotten used to having some sort of speech ready without emotionally investing in it very much. I would prefer it that authors and filmmakers weren’t put through this kind of emotional device for the sake of publicity or impact. I think it’s not a nice thing to do to people. I think it’s a disrespectful thing to do to artists, but that’s the way the machine works. As far as the Oscars is concerned, it’s easier than most because we’ve all been told that should we win, our speeches must not last more than 45 seconds. Some orchestra will start driving you out if you go beyond that. It’s not like you have to come up with some epic thing. It’s just enough time to thank three or four people. The Oscars themselves don’t present much of a problem, but with the Nobel Prize, I had to speak for 45 minutes, and I had about 10 days to write it, so that was a bit more of a challenge.

Photo credit: Andrew Testa

The post Kazuo Ishiguro on Life, Death, and the Movies appeared first on The Millions.