Famously, the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw once said that “England and America are two countries separated by a common language”. As a Brit who lived in Washington, D.C., for a decade and only recently returned to London, I’d say we’re separated by a lot more than that. Having been steeped in the book world for as long as I’ve been gone, I’ve also noticed a lot of differences between our publishing industries.

Differences Between U.S. Books and British Books as Physical Objects

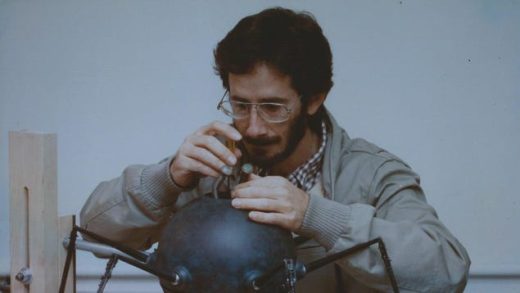

I joke that my superpower is being able to smell a trade paperback and tell you if it’s British or American; nothing smells more like home to me than the inside of a British bookshop, and more than once I’ve rushed straight to one the minute I’m through arrivals at Heathrow. (Love, Actually doesn’t show the person who doesn’t notice her friends waiting for her because she wanted to go and bury her nose in the latest paperback by her favourite author.)

But if you’ve ever looked closely at the bookshelves of a British bookstagrammer, you might have noticed something else, too: almost all the paperbacks are exactly the same size. There’s more variety in the U.S., except in certain genres — when I was a bookseller in the U.S., I spent a lot of time tending to our romance shelves, and it wasn’t just because it’s one of my favourite genres. It was because of how aesthetically pleasing it was that they lined up so nicely. British bookshop shelves are almost all like that.

That said, British paperbacks rarely have deckled edges or French flaps. I love running my hands over U.S. paperback covers. Many of them have a rough kind of quality that is pleasing to touch, and that we don’t really have in the UK. Here, though, sprayed or decorated edges seem to be increasingly common, and sometimes, thanks to exclusive editions, a way to send book buyers to specific shops, whether that’s indie bookshops or a chain like Waterstones.

And as for the look of covers, the art is endlessly debated among bookworms, with some preferring British covers and others American ones. But there are other subtle differences, too: American novels often tell you they’re novels; British commercial fiction often features a “shout line”, i.e. a pithy distillation of the story: “Have you ever been tempted to start again?” or “All she ever wanted was a little credit”. And while American ARCs often have covers identical to the finished copy, British galleys often feature a title or theme on the front, or a different design from the final copy, with the title only appearing on the spine.

Differences Between UK and U.S. Bookshops

Working in a bookshop feels very different in the UK from how it does in the U.S., too. I’ve only worked in one bookshop on each side of the Atlantic, so it’s hard to draw direct comparisons, if only because the British one I worked in was much more long established, with a much smaller staff working long days. This makes for a different vibe from the bigger, trendier American one where a large team came and went a lot more. (Related: although I love the hour-long lunch breaks that are the norm in the UK, I am desperate to find a bookshop job where I can work the shorter shifts I was used to in the U.S.; eight hours on your feet is not for the faint-hearted.)

Aside from the hours, there do seem to be other differences that apply across the board. Unlike in the U.S., where publication day is almost always Tuesday, the normal day in the UK is Thursday. But that’s much more flexible, not least because for big books, the date is set to coincide with the publication day across the Atlantic. Books are known to come out on Wednesdays or Saturdays, though – and with a few embargoed exceptions, nobody seems fazed if you put a book out a few days early.

Also, whereas many – if not most – U.S. indies have websites where you can order just about any book, British bookshops tend to have a curated online shop, and expect customers to call or email if they need to order anything else that isn’t specifically featured there. For that reason, I was especially excited when Bookshop.org launched in the UK; maybe it’s the ten-years-in-America in me, but it seems to me that if we’re trying to lure people away from certain online bookstores that make it very easy to buy any book…we should probably also make it easy to buy any book. A lot of people aren’t going to call or email if they can’t easily find what they’re looking for; they’ll just go to one of the other online places. But I digress.

Differences in Which Books Sell Where

Probably the most noticeable thing about the differences between UK and U.S. bookshops is the difference in the stock. Our biggest books tend to be homegrown, though definitely not always. Barack and Michelle Obama sell well in the UK, and the BookTok effect is alive and well, too. But British authors who may sell okay or even well in the U.S. are often juggernauts here — Richard Osman has dominated the bestseller lists for a while now, and others like Dolly Alderton have had big, passionate fan bases for years.

Many UK books aren’t published in the U.S., and those that are often aren’t given as much marketing as they deserve. (A major reason why I started The Brit Lit Podcast was to amplify them across the pond.) The Lido by Libby Page — a lovely book about a community coming together to save the local pool that features an unexpected friendship between a young journalist and an older widow — was huge in the UK when it was published in 2018, and it’s one of my favourites of recent years.

I always struggled to handsell The Lido — or Mornings with Rosemary, as it was rebranded — in the US, and I’m not really sure why, except perhaps for one final difference I’ll mention: the British market seems to love something called “up lit” — defined by the Guardian in 2017 as “the new book trend with kindness at its core” of which Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine was an early example. The Lido/Mornings With Rosemary is a great example of that sub-genre, and still gets recommended all the time in Facebook groups when someone is asking for a feel-good read. By contrast, my bookshop colleagues in the U.S. had a very different definition of a feel-good read. As long as the ending was somewhat hopeful, they put it in that category, regardless of what happened along the way. Up lit certainly isn’t a term that has travelled, even if some of the books have.

It’s been interesting to continue to observe the differences between the UK and the U.S. when it comes to books and publishing. I can see the good and the less good in both, and sometimes prefer one way of doing things and sometimes the other. I missed British books when I was in the U.S., and now that I’m in the UK, I miss the American book world. It’s one of the many ways in which, for better or worse, I’m now firmly mid-Atlantic in my outlook.

Source : It’s Not Just The Covers: Some Ways in Which the UK and U.S. Book Worlds Differ