The Blunt Instrument is an advice column for writers, written by Elisa Gabbert (specializing in nonfiction), John Cotter (specializing in fiction), and Ruoxi Chen (specializing in publishing). If you need tough advice for a writing problem, send your question to [email protected].

Dear Blunt Instrument,

Why is sentimentality in writing frowned upon? What makes it work?

– Todd Dillard

Dear Todd,

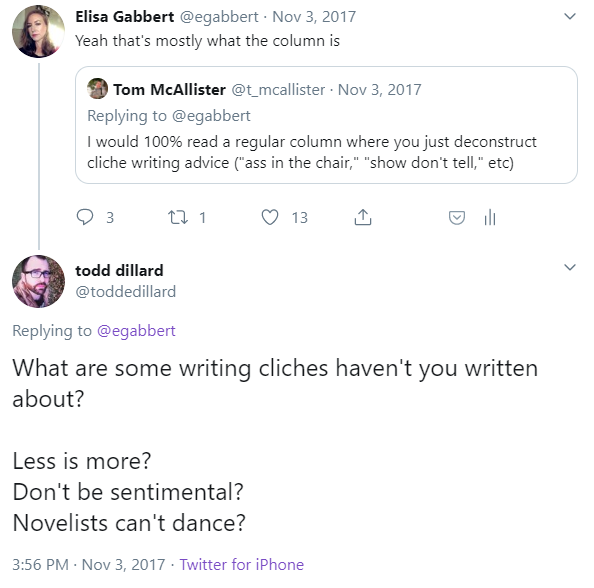

Since I think of you as a friend of the Blunt Instrument, I hope you won’t mind if I expose you a bit. I had a feeling we had talked about sentimentality before, so I searched Twitter, and found this exchange from a couple years ago:

From your comment, I’m guessing you might think “Don’t be sentimental” is cliché advice that deserves to be dismantled. Bad news, Todd! I happen to think it’s good advice, so instead of deconstructing it, I’m going to tell you why sentimentality should be frowned upon.

But first, let’s clear up what we mean by “sentimental.” It’s very tiresome to witness people in a philosophical or aesthetic argument over whether X is good or bad or exists or doesn’t exist when they haven’t first agreed on what X even is, and it’s clear they’re defining it differently. So let’s define the term, because I think this is where some confusion arises. The primary definition of “sentimental” in most dictionaries is not inherently pejorative (that is to say, negative). Merriam-Webster has it as “marked or governed by feeling, sensibility, or emotional idealism; resulting from feeling rather than reason or thought.” And Google’s dictionary, however that works, defines it thus: “of or prompted by feelings of tenderness, sadness, or nostalgia.” This is the usage implied in a phrase like “a sentimental melody,” or “feeling sentimental over you” (though “feeling sentimental” is nearly redundant).

It’s not sentiment or emotion itself that’s bad, it’s misused or overused emotion.

So, writing governed by feeling, especially poignant feelings—that doesn’t seem so bad, right? Right! Because that’s not the definition people are using when they describe writing as sentimental! What they’re using is the second definition of the word, which applies in different contexts. Per Merriam-Webster: “having an excess of sentiment or sensibility.” And, per Google, perhaps more helpfully: “(of a work of literature, music, or art) dealing with feelings of tenderness, sadness, or nostalgia, typically in an exaggerated and self-indulgent way” (italics mine). Safe to say that if someone is dishing out “Don’t be sentimental” as writing advice, or using “sentimental” to describe a piece of writing in a derogatory way, the connotations of excessive, exaggerated, and self-indulgent are baked in. It’s not sentiment or emotion itself that’s bad, it’s misused or overused emotion, and this is what writers, maybe especially poets, need to watch out for: unearned sentiment that feels mawkish, cloying, or cheap. In other words, laying it on too thick, or using emotional tropes to trick the reader into thinking they’re feeling something, when actually they’re just recognizing the outlines of a familiar emotion.

Of course, writers and critics may disagree over what counts as excessive or self-indulgent, just as we may disagree over what’s good or terrible. But this is my column (partial ownership anyway), so I’ll try to illustrate the point with some examples of what I would judge to be good sentiment and over-the-top sentiment. Let’s start with the bad, and I’m going to use an example by a man, because some people will want to say that sentimental writing is only frowned upon because it’s associated with women. (I would contest that assumption; I don’t believe well-read people think of sentimentality as gendered.) Billy Collins has been called “the most popular poet in America”—surely he’s not anymore, but still, he can withstand being used as an example here. He is also textbook secondary-definition-sentimental. Take the poem “Aimless Love,” which begins:

This morning as I walked along the lake shore,

I fell in love with a wren

and later in the day with a mouse

the cat had dropped under the dining room table.In the shadows of an autumn evening,

I fell for a seamstress

still at her machine in the tailor’s window,

and later for a bowl of broth,

steam rising like smoke from a naval battle.This is the best kind of love, I thought,

without recompense, without gifts,

or unkind words, without suspicion,

or silence on the telephone.

Look, I get that this can be read as a humorous, tongue-in-cheek poem—he’s not really falling in love with a dead mouse or, by the end of the poem, a bar of soap. But, on the other hand, it’s not actually funny, or at least I wouldn’t trust anyone who laughed at it. And I’d argue that by the end of the poem he’s really trying to make you feel something, something serious. He’s leading you there all the while, cat-and-mouse style. At first the idea of love in the poem seems ironic (wren, dead rodent); but by the second stanza the object of affection is much more plausible (pretty girl in a window), so already we’re forced to question if the speaker is partly serious—what they used to call “kidding on the square.” Joking, but not really. Because the serious theme of the poem is not bestiality or necrophilia (one hopes, one hopes!); the serious theme is the difficulty of real love. (Real love, which involves compromise—conflict—silence!) This is what makes the poem unforgivably sentimental, in my view—the way Collins uses cutesy, Disney-esque images (a mouse in a brown suit!), faux-disarming constructions (“I found myself standing”), smarmy emotion-triggering words like “heart” and “home”—to manipulate you into feeling something serious about a serious theme. But the occasion is ridiculous! It’s a bar of lavender soap! (I hate especially that it ends on the word stone, the poemiest word of all time. Has a poet never simply kicked a rock?)

You can’t define an adjective like ‘hokey’ or ‘corny’ by any clear objective standard.

Exaggeration that is actually funny, of course, is good. Also, I like to feel things! You can’t define an adjective like “hokey” or “corny” (both of which, by the way, mean “mawkishly sentimental”) by any clear objective standard, but some number of people are going to read it and make the puke face. If this is something you care about, whether people like me are going to make the puke face when we read your poem, all you can do is read a lot and figure out where you judge the boundaries to be—reading a lot is key, because that’s the only way you’re going to recognize clichés.

Let’s end with a short poem I find to be successfully emotional, not cheap or manipulative, but rather genuinely and mysteriously sad, though in some ways it’s exaggerated and ridiculous. It’s one of my favorite poems, also by a man (a very probably racist man, but those sensibilities at least do not show in this poem). It’s “Depression Before Spring,” by Wallace Stevens:

The cock crows

But no queen rises.The hair of my blonde

Is dazzling,As the spittle of cows

Threading the wind.Ho! Ho!

But ki-ki-ri-ki

Brings no rou-cou,

No rou-cou-cou.But no queen comes

In slipper green.

This is a poem I can read again and again and never paraphrase, because I never really understand. Sentimentality is feeling that’s too sure of being understood.

Before you go: Electric Literature is campaigning to reach 1,000 members by 2020, and you can help us meet that goal. Having 1,000 members would allow Electric Literature to always pay writers on time (without worrying about overdrafting our bank accounts), improve benefits for staff members, pay off credit card debt, and stop relying on Amazon affiliate links. Members also get store discounts and year-round submissions. If we are going to survive long-term, we need to think long-term. Please support the future of Electric Literature by joining as a member today!

The post Is Sentimentality in Writing Really That Bad? appeared first on Electric Literature.