Sophie Mackintosh on the looming threat of dystopia in 2019

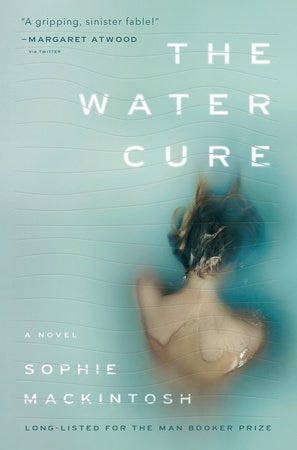

I n Sophie Mackintosh’s debut novel, The Water Cure, toxins have overtaken the world, and proximity to men is physically dangerous for women. Three sisters live with their parents on an island, a resort-like sanctuary where women come to be cured by the sea air, and by a series of “cures” administered by the family.

Over time, women stop arriving from the mainland. Then, the girls’ father, the only man they’ve ever known, dies. When three strange men arrive on the island, the women must decide how to deal with them — and with their changing impressions of each other.

Sophie Mackintosh is a celebrated short fiction writer, her work having won the White Review Short Story Prize as well as the Virago/Stylist Short Story Competition in 2016. The Water Cure was longlisted for the Man Booker prize in 2018.

Over email, we discussed the power of ambiguity, misogyny, and the looming threat of dystopia in 2019.

Deirdre Coyle: One fascinating aspect of your worldbuilding in The Water Cure is how little we know about the nature of the “disease” from which the characters are being sheltered. We know there are “toxins,” that women wear muslin to cover their faces, and we see “cures” being performed by the on the women. What made you decide to keep the nature of the disease vague, and the nature of the cures explicit?

Sophie Mackintosh: I am very much a believer in the power of ambiguity — how vagueness and insinuation, the things that edge around what is known, can be the most terrifying of all. But the cures to me needed to be concrete, because these are the things that we can see, as readers, through the foggy atmosphere. The cures are more important than the cause. We perform rituals of safety all the time, for fears or conditions real and imagined. In that sense it doesn’t matter if the disease is real or not. What’s important is what is enacted on the body, the illusion of safety and purity it gives to the girls.

We perform rituals of safety all the time, for fears or conditions real and imagined. In that sense it doesn’t matter if the disease is real or not. What’s important is the illusion of safety and purity it gives.

DC: Are any of these ritualistic cures based in reality, past or present?

SM: Water has long been seen as this curative, with real-life cures from history including ones similar to those found in the book, such as cold water immersion and sweating things out. I was on holiday in Budapest recently and getting into the thermal baths gave me an immediate sense of wellbeing, something primal — like the water could heal everything wrong with me. It’s such a basic element and yet one we can ascribe such magical powers to, something mystical and also essentially feminine about it. It’s the element of sea maidens, sirens, water signs and emotion. But there’s something dark and dangerous about water too, the ‘water cure’ being a traditional form of torture as well as something health-giving. I’m very drawn to ritual and to anything that promises me a way to feel better. To this idea that in order to keep myself safe I could make a circle of salt around me and hold my head under the water and go about my day, untouchable and reassured.

Water is such a basic element and yet one we can ascribe such magical powers to, something mystical and also essentially feminine about it. It’s the element of sea maidens, sirens, water signs and emotion. But there’s something dark and dangerous about it too.

DC: Certain elements of The Water Cure remind me of Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1915 novel about three men discovering a women’s utopian society. But while Gilman’s novel maintains that the women-only society is a utopia, in The Water Cure, we see the cracks in the women’s relationships with each other even before the three male characters show up. How do you see The Water Cure in conversation with other fictional women’s societies, whether Herland or Wonder Woman’s Themyscira?

SM: I had not actually heard of Herland before writing The Water Cure! So to me it was interesting to think about these ideas of female-only communities far apart from the world being a universal idea across the decades, with differing opinions on how they might turn out. In another comment online I read someone say about by book that “all the monsters are women”, and I found that interesting too — because of course there is good and bad in everyone and everything, and my intention was not to write a book that pitted perfect women against evil men, a super pure community corrupted. These are real women, and like real women they are often cruel to each other — they are siblings with their own dynamics and rivalries, they perpetuate violence against each other the way that women do in the real world too, even before the arrival of the men.

Misogynistic Dystopias, Ranked By How Likely They Are in Real Life

DC: Some of the chapters are narrated by one sister, others are narrated in chorus by all three. How did you navigate switching into a collective mindset?

SM: The collective voice came to me relatively easily — I saw it as almost a shared trance-like state between the three of them, this otherworldly connection that they have where their individual concerns and personalities become temporarily united. It transcended them. Technically speaking I found it helped to switch between fonts, for all the voices. It sounds really simplistic but it genuinely helped me. Maybe because I’m visual but I can’t imagine a sister as spiky as Grace ‘talking’ through Comic Sans, for example.

DC: In a recent piece for The Guardian, you wrote about how music affects coming-of-age. How do you think the total lack of pop culture affects coming-of-age for the women in The Water Cure?

SM: It was a challenge when writing it, for sure. I think because of the kind of teenager I was, living in the kind of place I was — isolated countryside, where difference was regarded with suspicion — pop culture was integral to my development and became a very important signaling, a shorthand to display who you were and who you wanted to be. I realized how dependent I was on these kinds of signaling when writing the characters of the girls. Who are you when you’ve grown up in a strange vacuum? What are the teenage rites when your music, your books, your media are limited so much in this way? What is a young woman if not something created by outside forces? Most readers think that the women in the novel are much younger than they are, and there is something disturbing in that idea too when you find out their actual ages, in that idea of infantilization, how the lack of pop culture means that the usual codified rites and milestones just aren’t there, and there’s nothing functional to take their place.

DC: In 2018, how close do you feel we are from this kind of dystopia?

SM: I don’t think we’re so far away from it at all. Maybe we’re not at a point where there’s a literal disease killing women that men are happily (or thoughtlessly) passing on, but for all the celebrated gains of feminism, we’re also seeing a pushback in terms of the normalization of [Men’s Right Activists] and far-right misogynist perspectives, women still don’t have autonomy over their bodies, and worldwide women continue to have their rights stripped from them and violence enacted on them. Women are killed by men every day all over the world, in the name of revenge or misplaced honor or spurned love, or just because they are there. Women take the burden of keeping themselves safe from these dangers that men don’t have to think about. Until this changes for every woman, we’ll never be too far away from it.

Women take the burden of keeping themselves safe from these dangers that men don’t have to think about.

In “The Water Cure,” Toxic Masculinity Is Making Women Physically Ill was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : In “The Water Cure,” Toxic Masculinity Is Making Women Physically Ill