The existential movement came into being in the 19th century and then slowly invaded the literary world. Existential literature captures the chaos and meaninglessness of our world. At a time when “things fall apart; the center cannot hold,” literature depicting existential dread is not an aesthetic but rather the need of the hour. Many a time humans feel that their day-to-day chores are a hamster wheel’s exercise in futility, and literature validates that feeling. When the adult world asks us to snap out of the void we carry within ourselves, existentialist literature assures us that it’s alright to feel this way.

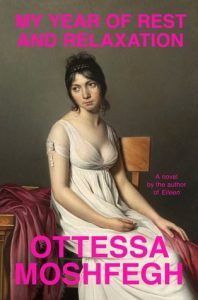

In My Year Of Rest And Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh’s unnamed protagonist is the dystopian rendition of Sleeping Beauty. She is a twentysomething art history graduate living the conventionally coveted life. She has an inheritance that pays for her lifestyle and the social capital that comes with being pretty. Despite having it all, her existential crisis has her in a chokehold. She is yet to process the death of her parents, with whom she hasn’t had the most ideal relationship. Her depression gets out of hand, and the perpetual emptiness she feels gains more strength every day. This is when she decides to go into a chemically-induced hibernation.

Growing up in a household where warmth and love were rarely bestowed on her impacted our narrator’s ability to invest in genuine interpersonal relationships. Her dysfunctional relationship with her friend, Reva, and her boyfriend further adds to her existential alienation. She is a cautionary tale warning the readers to take note of an emotionally deficient life. Moshfegh’s characters are always repulsive or are repulsed by themselves, and My Year Of Rest And Relaxation’s protagonist is no different. The narrator’s exhaustion and escapism are universal. Her need to escape herself, even when it has dire consequences, is relatable for everyone who can’t find a reason to get out of bed at all. Her need to sleep away her life is not suicidal, but rather self-preservational. Consciousness will demand having to come to terms with the fullness of her being and the existential crisis that is swallowing her whole. Moshfegh’s protagonist is way too spent to work on or out of herself.

Qiu Miaojin’s Notes Of A Crocodile introduces us to Lazi, a queer woman growing up in the Taipei of the 1980s. The plot centers around her existential dread while she tries to embrace her sexuality and find love in people who exhibit hot and cold behavior. The heartbreak of the youth is palpable in Miaojin’s writing. The harsh blows of a homophobic society and the highs and lows of first love are too much for Lazi to bear. Lazi writes,

“Most people go through life without ever living. They say you have to learn how to construct a self who remains free in spite of the system. And you have to get used to the idea that it’s every man for himself in this world. It requires a strange self-awareness, whereby everything down to the finest detail must be performed before the eyes of the world.”

She is highly intelligent and self-aware, which poses the question of whether being emotionally sharp is a reason why she is so unhappy and full of existential dread. Her desire for social interaction directly contradicts her desire to hide from everyone. Living in a society where queer people are thought of as transgressors adds to her fragmentary identity. Woven in between chapters focusing on Lazi, there are surrealist accounts of crocodiles who think and speak like humans but are not humans. These crocodiles don’t belong to the society they are a part of as they are constantly fetishized by it. These chapters further accentuate the theme of existential dread as the crocodiles stand as a metaphor for Lazi’s failed attempts at finding a sense of belonging.

James Baldwin said, “It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” While literature focusing on existential dread might not alleviate our suffering, it does give us a home, albeit fictional, to go back to. It binds us together with the rest of humanity and thus tells us that we aren’t the first people to feel lonely, and we definitely won’t be the last. We are suffering, but our suffering is not unique to us. It’s the universal human condition, and perhaps there is some solace in knowing that we are in this together.