Sophia Shalmiyev’s “Mother Winter” couldn’t answer the defining question of my life, but at least we were asking it together

Growing up with an alcoholic mother is a full-time job — the tending, the fretting, the terror. A somatic nightmare. But once my mother left me, I was not off the clock. At nine years old, I had retired from nothing. Instead I was bathed in an uncategorized grief, though I would not have known to call it grief for a very long time.

The trouble was that my mother was not dead when she abandoned me and did not return. She was breathing and living, going through the motions of a life just as I was. I wondered if she cried when she was alone like I did nearly every evening, looking up at the clean ceiling of my grandparent’s house, my new home.

Death was simpler to imagine. Easier to explain. I wanted a death when she left me because it felt a death. I wanted life to match itself but it did not.

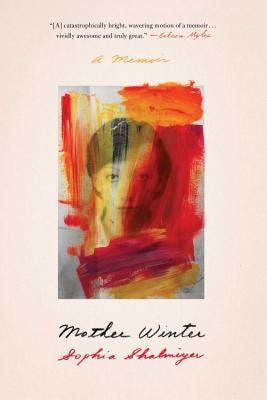

There are plenty of dead mothers to be found in mainstream narratives, or mothers who return by story’s end, but those aren’t the same thing as the loss of a living mother — a mother still in the world, just not the same world as her child. So when I read the memoir Mother Winter by Sophia Shalmiyev, it was like looking in the mirror and seeing myself, all blood and pulp and bruises, my body split down the middle by my motherloss; it lapped the salt of that wound.

Mother Winter chronicles Shalmiyev’s childhood separation from her alcoholic mother, Elena, and how she tries to find her mother later as an adult. She so perfectly conjures life as a child of an alcoholic though poem-like prose, describing a scene where she turns on a light and sees her mother limp, two men possibly raping her. I would have to learn about Elena by reading an instructional manual that didn’t exist. She describes her mother’s dark lined eyes and lacquered lips, the blue veins on her breasts and the desperate way she drank hairspray, men’s cologne. My mother, too, could get by on chemicals if needed: vanilla extract, Listerine, the bottles circled by her fuchsia lipstick.

Mother is a circle, Shalmiyev writes. A complete and perfect hole.

Elena is the ghost trailing Shalmiyev’s existence, and while many women grace the vignettes of Mother Winter, the book is indisputably about her: the search for her, and the failure to find a satisfying answer to the burning question I have also carried my whole life — how can a mother leave her child?

Shalmiyev’s father did not leave the cord intact for her mother to be found, letting Elena fade from view as he and Shalmiyev flew over the ocean from communist Russia to the United States for a new life where she would work for a feminist high school newspaper, Riot Grrl her mantra. Her stepmother Luda mused that she should feel grateful — why miss your whore mother when you are better off without her?

The book is indisputably about her: the search for her, and the failure to find a satisfying answer to the burning question I have also carried my whole life — how can a mother leave her child?

“Why miss your mother” was a question I heard too, and it shamed me. People probably thought it comforted me to hear that I was better off without my mother, but it did not. Telling a child their mother is scum, no matter how horrible she may be, is telling the child she is scum. You cannot separate the two.

Shalmiyev’s mother, like mine, was not dead, but an alcoholic. Shalmiyev writes her mother poems, imagines her. Every night for a long time I imagined my mother coming screeching around the corner into my grandparents cul de sac to take me in the night. I wanted something crazy to happen. But the fantasy stopped there. There was no new life waiting. There was only the life I’d always known, alcohol at the helm. My mother knew all the recovery lingo; she had been in and out of programs since she was a teenager. King Alcohol, she called it, before she knelt to worship.

It is one of life’s supreme gifts to find a book that seems to tell your story — not just the emotion of something familiar, but what feels like your exact heart. I’ve only felt this once before in my life, while reading White Oleander by Janet Fitch. In this sprawling novel, the young narrator is accounting for a maddening loss when her poet mother goes to prison for murdering an ex lover. Her mother is not dead, but taken. Shalmiyev says early in Mother Winter that she was stolen from her mother (though she rationalizes that her mother left her years before when she chose the bottle). I, too, felt that perhaps I had been stolen from my mother, that the courts were determined to keep us apart, setting up impossible tests and barriers that my mother would never be able to accomplish. She had to go to rehab, they said, she had to get a job, she had to show she could keep up a safe living situation for us, she had to she had to she had to. But how was this woman, who for a time could not even leave her bedroom, could not even make me one meal or take me to school, possibly do all of those things? Stolen. When I talked to her on the phone for our limited phone calls after she left, after she never showed up for her court date, we would muse how unfair everything was in life, how unfair it had all been to her. She would cry into the phone and I would comfort my mother for the loss of her daughter.

She would cry into the phone and I would comfort my mother for the loss of her daughter.

Shalmiyev says when she saw her mother and the men, she became the mother and her mother was the baby. I have felt I have been a mother most of my life, but only in the last four years have I become a mother to my own children. Only then have I felt the deepest need I’ve ever felt for my mother, but also the widest expanse away, the most disdain for her.

I can’t get her buttermilk smell off my mouth, Shalmiyev writes. She does not worship Elena, but she can’t shake her. I read Mother Winter to be a love letter in many ways to Elena but also to the other mothers Shalmiyev auditions: Feminists, writers, activists, painters, ballbusters, killjoys, sex workers, gay men. In this way, Mother Winter became a mother to me. I will turn to it again and again for truth, the electricity of the writing, the way Shalmiyev is unapologetically a human woman, motherless and brazen, holding her tampon in with one finger while she takes a shit and her children go wild around her.

Motherhood is not romanticized in this book, except in its undoing. It is the most romantic thing I can imagine, similar to the way Cheryl Strayed proclaims her mother as the love of her life. I know I will chase my mother’s love until the ends of the earth and when I arrive there not having found it, I will chase it some more. I will hold my own babies and feel the sensation of being an elder woman to someone and want the physical pressure above me, the actual press of another’s body shielding me, my own mother, the one who is supposed to offer these things to me, these guiding lines and animal knowledge, and I will feel only open air on my skin. I will watch my friends be mothered by their own mothers and bite my lips until they bleed in my mouth. I’ll smile, I’ll be the things she was not to me, but I’ll also be her. Like her, I won’t be able to tolerate alcohol in any amount, and like her, I’ll expose a sensitive skin to the knife of the world, and I’ll feel the way her body has been assaulted and taken from her time and again in my own body, how can I not? I came from her, her cells forming my own, and I’ll be her but I will also be myself, no numbing elixir at the ready besides my book companions, and occasionally, the weight of my daughter in my arms.

I know I will chase my mother’s love until the ends of the earth and when I arrive there not having found it, I will chase it some more.

After the birth of my son I knew I was finished having children. My body told me I was done and I listened. I laid on the table of Tami Lynn Kent, the Ted Talk “Vagina Whisperer,” while she did a myofascial massage on my “bowl,” her gloved fingers inside me reading my vaginal aura with pristine accuracy. She found the motherloss in my body immediately. She found the places I held that pain and had for so long. She prompted me to close my eyes and go to a happy place and visualize release. I have done meditation before. I have released my mother many times. This time I saw a black star sky, my spirit floating like a glowing outline. I was on my way to healing, soaring alone. But then something happened. My outline stopped and turned back, grabbed the hand of another outline, my mother, and carried her along for the healing. This was new. I felt peace. Shalmiyev writes, I could buy the ticket, take the ride, but never arrive at my body, clean and fed. Not until I cleaned and fed children of my own. Perhaps I had arrived back at myself, clean and fed, so clean and fresh and full that I was finally able to hand some of that to my mother’s hollowed spirit and ask nothing in return. It will be only this, I thought. Giving away this love will be the only consolation I will ever find.

Shalmiyev writes, Elena. Mother. Mama. You. I choose You. Says she would like to wear the equivalent of a medical alert bracelet: I lost my mother and I cannot find her — née Danilova. Yes, I thought. A bracelet would do nicely. I’d like one too.

9 Books on the Complexities of Mother-Daughter Relationships

When I was 25 and riddled with tension headaches and migraines, my motherloss still unsolved, my acupuncturist told me I was stimulating my umbilical region with the belly button ring I had gotten as a teenager. The piercing was triggering the mother zone, literally the physical place I had been connected to her, nourished by her body. That night I took the ring out in the shower, giddy at having perhaps found the culprit of my pain. A belly ring all along was slowing me down.

Why can’t anything ever be easy?

When I turned eighteen I knew time was up. Time was up on my childhood and the space in which my mother could have screeched up that driveway and reclaimed some life with me. I was going to community college. I was legally an adult and no one had custody over me. I felt astonished that my worst fear had happened — my mother never came back — and yet I was still standing. She missed it all. I missed it all. Life went on anyhow. I ate and smoked and breathed and fucked and walked and cried and drank I drank I drank and I tried to find her up my nose and in a bottle but those things were never really for me and offered only the ugliest pleasure. By 20 I was done with all that. I’ve stayed done.

I felt astonished that my worst fear had happened — my mother never came back — and yet I was still standing.

My mother is still not dead. She has never met my children. She saw me once before I graduated high school and we sat in my broke-down Chevy Malibu and smoked cigs with the windows up in an Applebees parking lot on the edge of town where she snuck me drinks that I paid for, and then had me take her to a liquor store so we could streamline our drunkenness, get down to some frugal and serious drinking. The photo albums I had brought to show her waited in the backseat for the right moment. I meticulously chronicled my own life the way I imagined a mother would for her children — I made my own baby books — but the books stayed in the backseat as I watched her throat move in the most desperate way drinking from a bottle of vodka as if it refreshed her, as if it were water, and I drank too and I knew I was drunk but would have to drive her back to the hotel she was staying in with the man who took her from me, stolen, and it was a pain to understand that my mother didn’t mind if I drove drunk, didn’t mind at all. She liked me this way. She played with my long hair. The photos remained unseen.

But still I choose her, no matter how many years pass. I cried in my therapist’s office weeks before having my son because I was ready to reveal my truth. That despite everything I still wanted my mother. I still somehow chose her and I always had. My mother probably thought me stoic, all my boundaries, all my self protection, but under all that, I wasn’t cold for her. My secret she would never know: For her I maintained a warm fire in case she ever wanted to come in from the cold.

Recently my mother tells me on the phone that maybe things all worked out for the best. I got to live in a nicer house with my grandparents than she could have ever provided me. I got to have birthday parties. Her voice trails off. My voice booms. “I never cared about birthday parties. I wanted you,” I said.

Bridgett M. Davis Explores a Family Secret: Her Mother’s Illegal Lottery

I chose you. Mother Mama Mary. I choose you.

The differences between my mother and Shalmiyev’s are probably plenty, though admittedly I conjoined them into one mother in my reading. But the main difference remains: My mother is found. I have her address. I ship her soft sweaters because I know she cannot walk anymore and will not leave her apartment and most certainly cannot stroll into her local Gap and try on a soft sweater, so I send them to her. I could fly there right now if I wanted. I could show up and make her look at me. I did it once with my boyfriend at the time. We planned a total ambush of detox and AA. Shalmiyev flew to Russia to find her mother with her at the time boyfriend, too, but they had no address. She packs a bag of American things her mother might like, carefully chosen gifts. The heart to do that is so big. Perhaps both of our journeys were fruitless. Perhaps they were not.

Shalmiyev has a son and daughter, as do I. She says of her daughter, watching her baby body stretch across the writing desk turned changing table, I think about how I want to be her so badly. I too would like to be my daughter, so safe snuggling or dancing, or even when she is mad and slamming doors around the house, her anger meaningless to my love. The more I love her the more my heart fills in. The more I love her, the more I ache for that same love but cannot find it.

Shalmiyev cringes when she finds that her small son has crumpled the photograph she has of her mother, one of the few talismans she treasures. His palm has crushed it and the photo flakes. I wonder if when Shalmiyev looks at photographs of her mother she sees the same immense beauty I see when I look at photographs of my mother. I see her frozen there, the most beautiful woman in the world. Perhaps more beautiful than she would have ever been to me had she fed and clothed me, had her love been there every day like a rug under my feet. The possibility of the love and the failure to deliver has cut her features striking to me, unknowable. My daughter will always see my familiar face and not think of untouchable beauty, but of home.

I see her frozen there, the most beautiful woman in the world. Perhaps more beautiful than she would have ever been to me had she fed and clothed me, had her love been there every day like a rug under my feet.

As I read I imagined myself and Shalmiyev conjoined motherless women. Holding our own children and feeling the weight of the aloneness, but also feeling the gratitude for somehow making it out alive enough to hold children at all. We wear the motherloss now invisibly. No one can look at us and know. Perhaps she, like me, holds the loss like a rock in her pocket, something to reach in and feel the rough edges of while walking in bitter cold air alone, imagining our mothers watching us somehow, as if life could be that magical, as if we might find them at the corner store, clear eyed and ready, and it’s all been a big mistake.

So how can a mother leave her child?

Shalmiyev knows, and so do I, and so do many others before us. She writes of Gertrude Stein whispering in her ear: But dead foremothers speak.“There ain’t no answer. There ain’t gonna be any answer. There never has been an answer. That’s the answer.”

How Could a Mother Leave Her Child? was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : How Could a Mother Leave Her Child?