Thomas Page McBee on his new book “Amateur,” about navigating masculinity as a transgender boxer

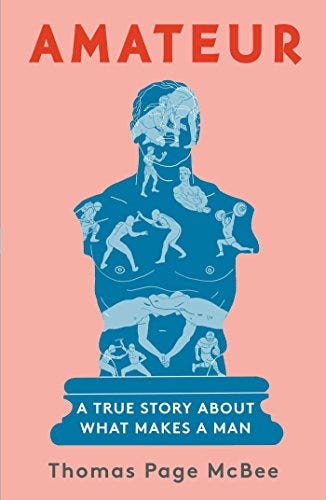

Part memoir and part anthropological study, Thomas Page McBee’s Amateur reads like a boxer skillfully deflecting a jab, only to land an stinging uppercut of his own. While the book’s nominal subject is amateur boxing — hence the title — McBee’s attempt to be the first transgender boxer to fight in Madison Square Garden becomes a foil for his investigation of fraught masculinity, both his own and in American society at large.

After Amateur was short-listed for the U.K.’s Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction, McBee and I caught up over tea in Brooklyn the day after Brett Kavanaugh’s inauguration, an opportune time to mull over the continued perniciousness of toxic masculinity in America, as well as his continued fascination with monsters, fictional or otherwise.

Meredith Talusan: So, I am talking to you the day after Kavanaugh’s confirmation, and I guess, when I read Amateur, I feel like so much of it addresses masculinity with a certain type of empathy and compassion. In the environment that we’re in right now, what is the value and what kind of space for empathizing with masculinity can and should be had?

Thomas Page McBee: I had to trace back in a genuine reported way, to “How did we get here? Why are men behaving like they’re behaving, and why am I feeling, as part of my socialization, an expectation to not show emotion or to not ask for help or to not be vulnerable? Or all these other messages that I’m getting? Where is this even coming from?” And so, it wasn’t that I necessarily set out to be compassionate to men broadly, but in asking that question, I got pretty quickly to boys, and how we socialize boys. And boys don’t have a choice about how they’re socialized because they’re children, so looking at the research, especially the research around development psychologist Niobe Way’s work with adolescent boys, male friendships are disrupted around adolescence by toxic masculinity. Around 14 years old, boys from very close male friendships will suddenly stop talking about their male intimate friends. Around the same age, they’ll start showing those dominant behaviors that are typical of toxic masculinity. And they’ll talk about how heartbroken they are to lose those friendships, but they still stop having that intimacy with boy friends. And they will say that the reason why is that they don’t want to be perceived as girly or gay.

Around 14 years old, boys from very close male friendships will suddenly stop talking about their male intimate friends. And they will say that the reason why is that they don’t want to be perceived as girly or gay.

So they’ll move away from that intimacy and what Niobe Way calls “the things that make us human” in order to act like men. So, for me, learning that, it wasn’t so much that I was looking for a reason to be compassionate, but I felt like, “What a heartbreaking thing that that’s happening to children.” I have empathy for the boys in that situation. I don’t have empathy for men from whom this aspect of masculinity isn’t limiting to them, who aren’t then being accountable or choosing to look at themselves, but I think a lot of the way dominant masculinity works is that you’re always shielded and protected from that truth so that you can keep upholding this system of masculinity and power related to it. It’s a whole toxic system we’re all in, and a lot of ways that men and women and people of all genders are never disrupting it is by never questioning it.

MT: And it seemed like boxing in the book functions as a space for physical confrontation, yes, but also ultimately becomes so much more about camaraderie.

TPM: Yeah. It’s literally that because that’s the cover of violence. The men in the boxing gym, their masculinity is not under threat at all. I think it gave them room to be intimate, vulnerable, physically affectionate. And part of what’s surprised me so much about fighting was that the people I was training with were asking me constantly about my mental state, my spiritual state, my physical body. They were affectionate, physically, in ways I’ve never experienced with men, and it was a time in my life where I had just lost my mom. So, I was having this community of men who were, in some ways, giving me what I needed than the people in my life otherwise because I, in my male body, wasn’t getting touched as much, and I needed that as someone going through grief. But it made me sad that the reason why that was possible was because no one’s masculinity was being questioned because we were fighting.

The men in the boxing gym, their masculinity is not under threat at all. I think it gave them room to be intimate, vulnerable, physically affectionate.

MT: So then coming from that perspective and also being in the unique position of being female-assigned and having these experiences, do you have specific ideas about how we can not just raise boys but also cultivate a more generally compassionate culture in terms of gender relations?

TPM: I wrote the book really trying to think about questions rather than answers, though I think asking the questions actually is part of the concrete solution. I have a few ideas. One is I didn’t realize that genuinely so many people who aren’t trans and aren’t women don’t know that they have a gender. Like, knowing you have a gender is kind of important because — it’s like knowing you have a race. It’s like white people often don’t realize that we have a race, and if you don’t understand that you have a race, then you don’t understand how that operates in the world. And it turns into an intellectual experiment for you to think about race versus realizing race is a structure.

And then, I think, doing the quieter work of asking, “How does masculinity affect me?” and how are you restricted by your own identity. Almost every guy I talked to for my book told me some tragic story about boyhood and a moment where they had to totally change something about themselves in order to fit in, something crucial to who they were, to fit into stereotypes of what a man is supposed to be. And I think a lot of men feel like that trade is just a part of being a person, and in fact, it’s the opposite of being a person.

And so, then, for me, the next step was like, “Well, exactly what is this? What does this mean, and how is this showing up in my life?” So, for example, with sexism at work, some basic things I learned were like, everything that I felt from a feminist place before my transition had been useful was now the opposite of useful. So, I often was very assertive, often bringing my opinion forward and really advocated on my own behalf, in terms of meetings or with superiors or whatever, and actually, that was the opposite of useful for women on my team, for example, when I [did that], in this body, just because people listen to me more. So what was more useful is advocating on behalf of the women on my team or making room for their voices or being quiet or doing emotional labor or all the stuff that [it] makes sense was not in my wheelhouse, because I learned to do the opposite before my transition.

In Praise of Tender Masculinity, the New Non-Toxic Way to Be a Man

MT: I was really interested in those moments in the memoir when you confront your own male socialization. Do you think men have incentive to engage with the way their masculinity is oppressive, when they’re on top of the totem pole? What’s in it for them?

TPM: I think that goes back to your original question about compassion and in a way for me it’s like my own story is the way I can explain this or understand it. I transitioned when I was 30 and I spent those first four years, first of all very aware of the privileges I was experiencing because obviously, just to be clear, I had incurred an incredible work trajectory very quickly. I was very aware in small moments that when I spoke, people would listen or lean in or I could silence rooms with my voice. All of that was true. I walk down the street at night and would not be afraid. Not only not be afraid but women would cross the street to avoid me because I was now a threat. Everything about my life in certain ways, and in really important ways, became a lot easier and not just because I was a man, but because my gender was legible and prior to this I was androgynous, people didn’t know what to make of me. That all was true, but also at the same time I was very aware that almost I was becoming an island. When I was by myself I felt happy in my body but I would leave the house and I felt more and more isolated. The ways I was meant to behave felt very constricting and I was getting that message constantly. It was in so many ways that were small it was hard to totally put my finger on.

For example, I did notice that people stopped touching me except for people I was having sex with. I just felt almost radioactive. If I talked about how I was feeling about something, I could feel the way people would create space rather than have a conversation about anything vulnerable. I felt like I was losing things about myself from before my transition that I actually really liked, things I guess you would call feminine traits though they’re not actually gendered really. They’re what we reward in women and what we don’t reward in men. All of that was happening but is was subtle and it was making me uncomfortable and making me sad but I couldn’t put my finger on it.

I felt like I was losing things about myself from before my transition that I actually really liked, things that we reward in women and we don’t reward in men.

Then after my mom passed away very suddenly, I think being in grief just really threw that in very stark relief because when you’re in grief you need support, you need to be able to express yourself. I think that combines with the fact that this was 2015 now, so this is like four years after I started testosterone, I felt in myself a lot of anger and I felt in the culture a lot of anger. And that was when I got in to a bunch of near street fights with men. I think that was the crossroads for me where I was like I need to figure out what’s going or I’m going to become one of theses angry fucking white dudes. I’m just marching in a direction despite my politics, despite everything else, the way I’m having interact with the world feels like I don’t have any space to be my whole self.

MT: Is it tough for you to be a man right now at a time when women are so embattled, especially as a person who has shifted from being perceived as a woman to being perceived as a man? Is there any kind of loss of community? How are you engaging with the fact that so many people are so angry at white men right now?

TPM: I think part of it is understanding that I’ve lost community and part of why I think I’ve been going through all this is to actually find where my place is within the human family again, because I know it’s not just with cis men who are behaving badly. That’s not where I want to line up my energy. On the other hand I pass as a cis man. So in many ways that means when I look at myself I feel happy because that’s how I wanted to feel. But when I leave my house, again, I feel like all the markers and identity things that made me very visibly queer prior to this don’t translate any more. Nobody knows that I’m trans most of the time. I think understanding that privilege for what it is and seeing the benefits means understanding that maybe I don’t always get to be my whole self in every situation.

Yesterday, I was walking down the street. I took a long walk from Manhattan to my home in Williamsburg and I was crossing Williamsburg bridge and this woman just came, yesterday was a hard day, she came plowing forward. I could tell she was in a mood where she was like “I’m not fucking moving over for any guy. I am not.” I like, fell into the bike lane ‘cause she was just storming ahead. She knocked me off my path. Not that I was storming towards her, I was actually trying to be very “I’m going to move out of every woman’s way today, more than normal.” I felt the anger. I felt being the target of it. I understood why she was angry and I see that I must’ve blown up something that makes women angry and they don’t need to know me or my politics or understand me.

I don’t need to walk around every day and have everyone get that I have this experience. I think a lot of trans people [who] pass, we don’t get to signal that to everyone and that is okay. If I’m a passing trans man and people don’t get that I’m having this rich and nuanced experience and they’re strangers on the street, well, that’s fine. I’m getting a lot of privileges for being a passing trans man. The justice of that is equaling out to me. I think being more clear on what the fuck is going on and actually having more of an engaged relationship to my own gender and getting to find a way to advocate for the things I believe in through this body, it feels like I’ve found a lot of community in a new way through that way of thinking and speaking.

If I’m a passing trans man and people don’t get that I’m having this rich and nuanced experience and they’re strangers on the street, well, that’s fine.

MT: Speaking of being socialized in a gender, I was really affected by the idea in your book that you have to learn how to want to hit somebody, which I had never thought about. I grew up very much with pacifist values. That’s something you really have to get over.

TPM: I’ve been thinking about [that] a lot because even at the time, my coach kept calling it “coming forward.” At the time I thought it had to do with masculinity in some sort of way. You know, like men are taught to be more aggressive and what does that mean, or is it testosterone, which it’s not. But lately I’ve been thinking a lot about how powerful it was to learn to come forward, especially when you’re not socialized to do so, because learning how to fight is really an important part of being human. I think that people who aren’t socialized to fight, learning the way to do it in ways that are helpful and productive or at least consensual, as in this case, is actually really important part of being a person. I also was a pacifist so this is a really strange thing to learn, but now that I know it it actually feels like, wow, women in general need to be taught how to do this, trans people in general, and people of color and all kinds of folks need to, if they don’t have the skill set this is actually really important not just for the physical ability to do it, but for the way it makes you feel about yourself.

MT: Do you think this investigation of masculinity is going to continue? How is your thinking evolving coming out of this book and what are your other current things you are interested in?

TPM: I’m thinking a lot about monsters, especially in relationship to trans people and the media narratives around us. Just how the stories, not just about trans people but all of us, the stories we tell about people are who they become or how we come to see them. We often lack real nuance or ways to understanding people who are marginalized at all in our culture and it becomes very easy to moralize about bodies, and we’ve done this throughout time and monster narratives are great way to look at that.

It’s the 200th anniversary of Frankenstein, which is one of my favorite monster stories. I think I love that story so much in part because Frankenstein is an invention of this guy. Like the guy who invented him was the monster. In fact Frankenstein’s monster is a very empathetic figure if you reread the book. He just wants to be part of the human family and in fact everyone who’s rejecting him is the monster. His monstrous behavior only comes from realizing that he won’t ever be able to part of the world and he’s going to be completely alone and isolated. He’s not monstrous to be evil, he’s just mad and he feels lonely. I’ve been thinking a lot about the way we blame people for natural reactions to being cut off from basic human needs and then the way they behave in response to that.

Then also I’ve been thinking a lot about people who live in rural communities who are not our expectations of who lives in rural communities. It’s all about binaries. When we are committed to a binary understanding of each other, only bad things happen.

When we are committed to a binary understanding of each other, only bad things happen.

Many urban people think only urban people have the right perspective on the U.S. and where the U.S. should go and rural people are X way and they don’t know anything or whatever the story is. Or about the Trump election — West Virginia in particularly was framed as the problem when in fact the don’t facts back that up, the ground zero for Trump voters ended up being pretty standard with the rest of the country in terms of Republican districts. But West Virginia held this shame of everyone. In fact there are plenty of queer people in West Virginia doing amazing work that nobody knows about. I’m just really interested in stories where our notions of what people are or who they are are binary and require no nuance and allow us to prop ourselves up, but actually spending some more time really understanding would give us the tools to be more thoughtful, maybe learn something and talk more and deeply about what’s happening in this culture right now.

How Beating People Up Helped Me Find a Less Toxic Way of Being a Man was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : How Beating People Up Helped Me Find a Less Toxic Way of Being a Man