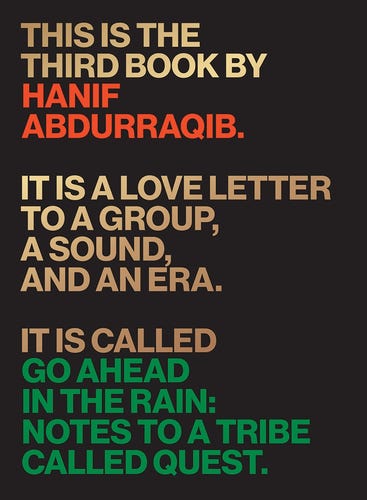

“Go Ahead in the Rain” Is a fan’s narrative on a Tribe Called Quest that gives readers the language to imagine a better world

I ’ve spent most of my days lately oscillating between rage and abject terror. So when midnight turned one year to the next last month, I couldn’t help but feel grateful that we’d finally made it. Where exactly, I wasn’t sure. But I had been sure that there was a finish line that if only we could cross we’d reach the year we could breathe again. I was wrong (like very, very wrong), but I’m holding out for March being the month it all turns around. Because in spite of my wiser self, there’s hope in me yet.

I’ve said all of that to say this: When I first read Hanif Abdurraqib’s essay collection, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, last year, I felt like I was watching someone who had overheard me and my best friends over the past decade in the moments we’d wept and celebrated and raged to the soundtrack of our favorite bands turn those moments into (beautiful and heartbreaking and celebratory) prose. I saw an urgency, a love—and perhaps most importantly—a quiet sense of hopefulness on the page that made me think, maybe, Abdurraqib might just be seeing me right back.

So if Go Ahead In the Rain is the book about the Midwest, hip-hop and what can be made possible if only we find our people and hold tight to them that I never knew I was missing but I always needed, then Hanif Abdurraqib is the writer every one of us could probably use right now.

Leah Johnson: This book has been described as a “love letter” and a “fan’s narrative” but much less frequently as a biography, though that is, in large part, what is happening throughout. How did you approach the writing in a way that you believe made it diverge from the traditional biography style?

Hanif Abdurraqib: I think a traditional biography requires a lot of access — to people, to history, to archives. But beyond that, it also requires a type of confidence that comes with expertise, or a desire to consider oneself an expert. I could have gotten the former, but felt pretty far away from the latter, fairly early on in the process. I realized that what I was searching for wasn’t exactly the ability to call myself an expert on this group, or this music, or this sound. I was searching, instead, for meaning — or an unpacking of what it is to have this love for people you will never meet.

Tribe were very much big homies for me when I was young. The way I listened to them and the way that listening afforded me to see the world was singular. It was like someone older throwing an arm around my shoulders and leading me through the treachery of youth. How can I have this impossible connection to these people and live a whole life where we’ve never met? I’ve got nothing but their sound and the paths that sound opened up. I wanted to allow myself some room to be wrong. I wanted to say sure, I am perhaps clouded by my love, and so I don’t want to talk to this group and have them tell me it wasn’t all as special as I imagined it. Give me my memories and nothing else.

I was searching for meaning — or an unpacking of what it is to have this love for people you will never meet.

LJ: During so much of They Can’t Kill Us, I read along like, “No one else would think to put Johnny Cash in conversation with The Migos like this!” Since this book was your direct follow up, did it feel like a radical gear shift, craft-wise, to narrow in on one genre and one artist like this?

HA: A bit, or at least it was difficult at first. The thing about They Can’t Kill Us is I could depart from an idea, and not feel obligated to return to it. Here, as far as I wanted to steer away from the central star guiding the book, I always had to return. There were some parts cut because I went too far away from it all. I had to be really honest with myself, on some shit like “does anyone really care how I can make a thread from Natalie Maines to Q-Tip?” and in the empty living room of my own apartment, I could say “hell yeah people need to read this,” but things like that pulled so far out of the book’s context. And this is a book that is already demanding a lot out of a reader. I’m asking readers to trust me, no matter how far it seems like I’m pulling them away from the road, I’m promising them that I’m always going to come back. I’m promising that we won’t always end up in the same spot on the road, but that the road will at least keep leading us to the same place. I take that trust seriously, and so writing this book was working through some very honest things with myself.

LJ: With both Go Ahead in the Rain and They Can’t Kill Us, music and memory are inextricably linked. What does your research look like when the history of an artist is so closely tied to your own personal history?

HA: In the most unspectacular of ways, my research is mostly watching or listening to things that trigger memory. I have so many times where I find myself wondering if I actually experienced something, or if it was all a dream. Particularly moments from my childhood that revolve around music. Did I actually stay up all night watching tapes of Yo! MTV Raps on the nights my parents weren’t home, or am I remembering several nights and just forcing them together for the sake of my own romantics? There was that thing in the book about Chi-Ali, and his freestyle on Yo! MTV Raps, and I knew I remembered it. I knew I had watched it with my older brother and I knew I had listened to the tape of his debut album after it. I could close my eyes and remember the floor I was sitting on when I watched it, and I could remember exactly what Chi-Ali was wearing. But I needed to see it again, nonetheless. I had to look it up on YouTube to confirm what my memory was trying to tell me. I think so much of my research is convincing myself that I’ve actually lived the things I’m trying to recall. And a lot of it is the frivolous watching of videos or spinning of samples or whatever. But that isn’t the answer anyone came here for.

What Do Bruce Springsteen and Chance the Rapper Have in Common?

LJ: The fact that the book is called “notes to” instead of “notes on” struck me when I realized you spent the book switching back and forth between speaking to us as readers and then directly to the group. How did you think about the mode of address when you set out to write this book?

HA: Well, I wanted it to be a conversation with both the readers and the entire legacy of this group. And I wanted it to feel like we were all in a room or around a table. The direct address to the group members and then the direct address to you, reader, populates the space a bit differently. I am so opposed to creating more distance with my work. There is already a built-in distance that comes with the reading of a book by a person you don’t know or see or talk to, and I’m comfortable with that. But in terms of how a book is addressed, or what the speaker is asking, I’m trying to build the room that our real lives might never afford us: a room where, over our shared loves or passions or curiosities, we can kick some questions around.

LJ: I’ve been reading the book on the train for the past few days, and every time I pull it out someone stops me to talk about it. New Yorkers aren’t stereotypically affable people, but something about A Tribe Called Quest has brought out some of the best conversations with strangers I’ve had in my time living here. Thinking about this in terms of community, but also coastal beef, what do you think it is about our regional relationship to these artists that manages to produce such instant, visceral connections for us?

HA: I can’t speak for New York, and even if I could, I’m sure no one would hear me over the shockingly consistent hum of sirens and horns the city produces. But, I also think all of the time about what it is to be from a place, and how much shame and pride that can offer to someone, sometimes in equal measure. And to have a group that came out of Queens and is not only beloved, but vital to the architecture of American music feels like a burst of pride that can cut through whatever regional shame might exist. So much of my writing of this book was also writing about how I grew up in the Midwest, longing to touch the cities being rapped about in the songs I most listened to. And so I hope there are people from New York who look at the book and simply want to point at it and say they lived some small part of what made Tribe special. Also, sorry for the bad joke about horns and sirens.

I think, ultimately, it means that there are some revolving universal markers in the music many of us love that begin geographical, but then branch out.

Music is at our fingertips now, it’s so easy to listen to songs, but it has gotten harder to track down stories that make the songs special.

LJ: I feel like there are so many artists that you have a wealth of knowledge on and could have crafted a book around. Why did you choose to chronicle A Tribe Called Quest?

HA: I have been especially worried about legacy, and the transfer of information from one generation to the next. Generations younger than ours know A Tribe Called Quest, surely. But I realized that there were many people who, in 2016, didn’t have a grasp on their impact and how that impact had echoed throughout decades, in rap music and beyond. People who didn’t understand how the production ambitions of Q-Tip fueled an entire sound and scope of ideas. And so I didn’t want that to get lost in translation of whatever gets passed down and down and down. Music is at our fingertips now, it’s so easy to listen to songs, but it has gotten harder to track down stories that make the songs special. I wanted to offer the best I could.

LJ: You wrote about the group’s SNL performance and final album in 2016 shortly after both the election and Phife’s death where you said: “Writing about music today feels even more small and trivial than it usually does. The times are urgent, and I know nothing but going back to what I love, but music still feels tiny and disposable.” Now, years away from that release and from the election that continues to do what we feared it would, what (if anything) has changed for you in terms of approaching music writing and/or listening?

HA: I think it still feels small and trivial — at least the act of it. But not the way it sits in the world, and what it is capable of articulating as far as unraveling the violence, or rage, or anxiety of not only this moment, but of so many of our living moments. I turn to songs not for healing or not even to make sense of the world. I turn to songs as a window into a different world entirely. And so the work of my writing is to try and give language to the world I see through the lens of a song I dig or an artist or album. What I’m trying to do is shape a world outside the current one, and I’m trying to make it slightly better. But, it’s hard to do that while also reminding people of how many fires there are everywhere.

The work of my music writing is to shape a world outside the current one, and I’m trying to make it slightly better.

LJ: When it’s time for someone to write a fan’s narrative of Future (I’m feeling like it could be called Turn On The Lights or Blood On The Money maybe?), what do you think has to be at the heart of that story?

HA: I think any narrative on Future has to include something at the heart of it on masculinity and self-destruction. The band Stars has this album called Your Ex-Lover Is Dead and it starts out with a recording of the lead singer’s father saying “when there is nothing left to burn, you have to set yourself on fire.” And ain’t that the whole thing.

About the Author

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist, and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio. He is the author of The Crown Ain’t Worth Much (Button Poetry, 2016), They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us (Two Dollar Radio, 2017), & Go Ahead in the Rain (University of Texas Press, 2019).

About the Interviewer

Leah Johnson is a writer, editor and hopeless Midwesterner currently moonlighting as a New Yorker. Leah received her MFA in fiction writing from Sarah Lawrence College and is a 2018 Kimbilio Fiction Fellow. Her work — which can be found at Bustle, Electric Lit, Cosmonauts Avenue, The Establishment and elsewhere — is centered on the miracle and magic of black womanhood.

Hanif Abdurraqib Knows the World Is on Fire, but Music Can Still Offer Us a Way Out was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : Hanif Abdurraqib Knows the World Is on Fire, but Music Can Still Offer Us a Way Out