Translated by Polly Barton

Japanese folktales and tales of yore are riddled with female ghosts and spirits, and I’ve been fascinated by them since childhood.

Into adulthood, it occurred to me that what draws me to these female spirits is the way that they expose the true nature of people leading a regular lives in society, which they’ve grown accustomed to hiding without a second thought. I asked myself why it was that I liked female spirits more than the male ones. I suppose that being a woman myself had something to do with it, but there was more to it than that: the female ghosts and spirits seemed to me simply more interesting, more full of character. Female spirits deviated wildly from the way that women are demanded to be by Japanese social norms, and it was that discrepancy that attracted me. As well as a sense of surprise at how unusual they seemed, they generated in me a feeling of familiarity—as if what they were portraying was a part of myself as well. Maybe I had a wild lady inside myself, maybe I myself was a wild lady as well—these thoughts brought with them all the joy of a revelation. It also made me think afresh about Japanese women, myself included, who, so long as they don’t die or assume an entirely different form, remain unable to reveal their true natures.

Folktales and tales of yore have lots of geographical variations, and can undergo further changes when they’re set down in certain versions by particular artists. The versions of the tales I’m relating here are the ones that I read and heard when I was growing up. Also, admitting this may get me in trouble with the experts, but I don’t make any strict distinctions between ghosts, monsters, yokai and so on—I tend to think of them all as kinds of wild ladies.

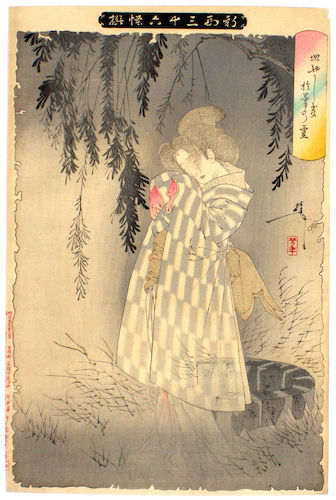

1. Okiku

Like the character of Kikue in Where the Wild Ladies Are, I grew up in the city of Himeji, where Himeji Castle is located. On school field-trips or when relatives came to visit, I would go up to the castle, and there, inside its grounds, stood the Okiku Well.

After becoming dragged into plotting of the men around her, Okiku is falsely accused of the loss of one of the house’s treasured set of ten plates, and eventually killed and thrown into a well. As a ghost, she emerges from the well each night, looking terrifying, and forever counting the plates: “One, two…” Getting to 9, she then exclaims, “Ah, there really is one missing!” But knowing her own innocence, she begins to counts again. For those who conspired to her take down, this spectacle must serve as a harrowing reminder of their deeds. As superpowers go, becoming a ghost and counting plates may seem relatively tame, but there’s something about this simplicity that conveys the depths of Okiku’s resentment. Living in a mansion echoing with the sounds of Okiku’s counting and the smashing of plates, those who destroyed her are drawn ineluctably to a bad end themselves, as if being swallowed up by the grotesquery they created.

As superpowers go, counting plates may seem relatively tame, but there’s something about this simplicity that conveys the depths of Okiku’s resentment.

In Japan, the season for telling ghost stories is summer, so that’s when TV adaptations of ghost stories are shown. Watching the TV adaptation of Okiku’s story as a child, and seeing the Okiku Well which really existed in the city where I lived being presented on TV as something fictional gave me the strangest sensation, like reality and fantasy had collided. It also made me feel very proud of Okiku. While writing WTWLA a few years ago, I visited Himeji Castle for the first time in over a decade, and saw the Okiku Well again. Recently restored, Himeji Castle seemed to me unnaturally white, but the Okiku Well looked to me just as it always had done. While there, I caught sight of a young boy visiting with his mother, looking into the well and imitating Okiku’s voice counting the plates: “One, two, three…” It strikes me as truly great that even into the 21st century, Okiku’s legacy lives on in that region.

Okiku planted inside me the awareness that horror is all around us in our every day lives—that it isn’t only scary, but also can generate feelings of familiarity and even strength. Of all the ghosts living inside me, she’s always number one.

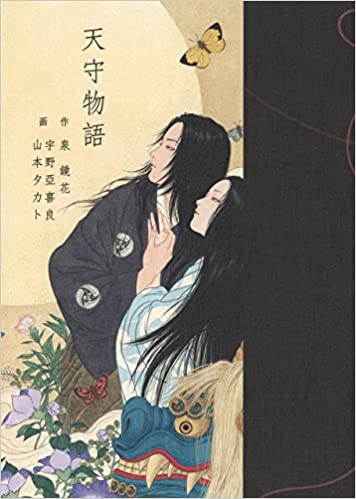

2. Osakabehime

As an adult, I discovered the existence of another wild lady in Himeji Castle: Osakabehime, a yokai who resides in the castle keep. In fact, there’s a small shrine in there dedicated to her. She also appears in Izumi Kyōka’s play Tenshu Monogatari [The Story of the Castle Keep]. She is waited on by a fleet of retainers, also spirits like herself, and is at loggerheads with the “world below” i.e. the world of humanity. She is self-possessed, cruel, and powerful.

In The Story of the Castle Keep, Zushonosuke is a human figure able to come and go between the two worlds, ascending to castle keep. Eventually he chooses the world inhabited by Osakabehime. Osakabehime has a sister called Kamehime, and the two of them take it in turns to visit one another in the castles that they inhabit. It recently occurred to me that they have a relationship a bit like Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell going between Monk’s House and Charleston.

Looking down from the Himeji Castle Keep, you see the Okiku Well directly below. It seemed like Okiku and Okabehime couldn’t have not known about one another’s existence, so in writing WTWLA, I decided to include a story depicting a loose sisterly bond between the two of them. With wild ladies both above and below, I can’t help but thinking that Himeji Castle really is a special place…

3. Kuwazu Nyobo [The Wife with a Small Appetite]

Japanese folk tales and ghost stories feature many female spirits. Taking on human form as they do, these spirits are very well informed about the nature of the ideal Japanese woman: she must be beautiful, quiet, perceptive, hard working, and devoted to her husband. The people around this “ideal woman” exploit these characteristics to take advantage of and deceive her. And yet, when the truth is outed and the spirit shows her true form, it transpires that she is nothing like the ideal woman whatsoever. After revealing themselves in their entirety, the female spirits make a lunge for the humans with fangs bared.

People speak about this true form as terrifying (and sometimes, as a kind of terror unique to women) but if that was all that it was, these stories wouldn’t elicit fascination in the way that they do. People want to see more of these women’s true selves. We learned long, long ago from stories that there is always another side to this figure of the ideal woman. And yet, here in the real world, we continue to demand that women embody this ideal. I find this unbelievably stupid. Come on, we know already that’s impossible!

We learned long, long ago from stories that there is always another side to this figure of the ideal woman.

The kuwazu nyobo, or “the wife with a small appetite,” is a yokai with a second mouth at the side of her head. She appears to a man who goes around making the stingy-hearted and ridiculous claim, “If I take a wife, my food costs will increase, so I want a hard-working woman with a small appetite,” and the two promptly get married. The wife with a small appetite works hard and doesn’t eat a bite in front of her husband, so she appears to his selfish eyes as the ideal woman. And yet, rice and other ingredients keep disappearing from the house. Beginning to suspect that his wife is eating in secret, the man spies on her. He discovers that, when she thinks he’s not around, she cooks up a great load of rice, which she then forms into onigiri and tosses one after the next into the mouth at the side of her head. When the man announces that he wants a divorce, the woman reveals her true nature, and attempts to abduct the man. He narrowly escapes by hiding in a marsh where irises are growing, known for their power to ward off evil spirits.

The great thing about the wife with a small appetite is the look of composure on her face, as the mouth at the side of her head gaily chomps away at vast quantities of food. I can fully empathize, and I’m pretty sure there are a lot of other people who can relate too.

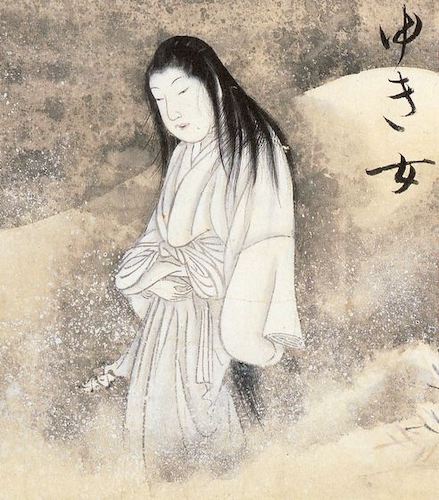

4. Tsurara-onna [Icicle Woman]

This is a yokai who appears in the cold parts of the country in the winter when the icicles begin to form, and disappears when spring comes and things start to get warmer. She’s very pale and very beautiful.

One night as a blizzard rages, a beautiful young woman appears at the house of a married couple, asking for a bed for the night, as the bad weather has meant she is unable to get home. The couple let the woman stay, but the blizzard drags on, and the woman ends up staying in their house for days. One night, they invite her to take a bath, but she refuses. The couple is insistent, though, so in the end the woman heads to the bathroom. She is in there so long that the married couple goes to check on her, only to find her gone. The only trace of her is the icicles hanging from the ceiling.

Her story reminds us that anything at all can have a spirit.

In another story, a man becomes lovers with a beautiful woman, who appears as if from nowhere, and the two get married, but when spring arrives, the woman disappears. Believing that she’s run away, the man takes another wife, but when winter comes around again the woman returns, and angrily accuses the man, asking why he’s taken another wife. “Because you just disappeared!” replies the man! “Don’t bother to come back again!” At this, the woman transforms into an icicle that pierces the man’s chest, killing him.

I like this second story. Seen through human eyes, the woman’s behavior seems selfish, but from her perspective, disappearing when spring comes is a matter of course, and so her accusation of her husband is deathly serious. That always seems tragic to me. And then, in the blink of an eye, she returns to her true self, and stabs the man she loves with her own body. This seems to me to represent the true nature of an icicle: simple, unwasteful and wonderful.

She may not be as well known as the yuki-onna (snow woman), but there’s something about that little-knownness, and her overall sense of restraint of which attracts me to her. Her story reminds us that anything at all can have a spirit.

5. The Woman Who Became a Dragon

When I was younger, I adored Miyoko Matsutani’s book, Taro, the Dragon Boy. Matsutani drew inspiration for the story from a folktale where a young boy climbs on his dragon-mother’s back and razes a mountain so as to create land for farming. Matsutani’s book begins as Taro goes venturing up to the lake far to the north search of his mother, who has changed into a dragon. When he finally reaches her, she tells him the story of how she morphed into a dragon.

Like Taro himself, she grew up on barren land not fit for farming grain. After losing her husband, she was forced to work throughout her pregnancy, accompanying the villagers who went to work in the mountains. While they were off laboring, she was asked to make their food. Catching three char fish, the woman grilled them and waited for the villagers to return, but they took their time, and eventually, unable to withstand her hunger any more, the woman ate all three char herself and transformed. She’d forgotten the old local superstition, that if you eat three fish you become a dragon.

Through the tears of a son who felt true pity for his mother, the woman who had become dragon was able to return to being a human.

Rereading this story in order to write this ranking, it surprised me to find the vivid description that the story gives the hardness of pregnancy. I suppose I wasn’t in a position to notice that when I was younger. Clearly suffering from morning sickness, the woman felt nauseous when she ate; the char fish lying in front of her were the first thing that she’d really had an appetite for in a while, and was therefore unable to resist the temptation. After transforming into a dragon, the woman gave the newborn child to her mother to look after. Her son Taro was given crystal orbs to suck on, and grew up healthy and strong. It later turned out that these orbs were his mother’s eyes—she had become blind in order to nourish her son, travelling to the northern lake in search of somewhere to live out her days.

Discovering all this, Taro doesn’t blame his mother for eating all the fish herself. Instead, he declares that the problem is that not everybody had enough to eat. Borrowing strength from his mother, and the animals, people and demon he’d met on his journey, he razes the mountains, thus creating fertile land for planting crops. Through the tears of a son who felt true pity for his mother, the woman who had become dragon was able to return to being a human, and regain her sight.

This story, which Matsutani wrote while breastfeeding her newborn baby, has true kindness at its core—kindness which says that if an environment or system makes humans unhappy, then it must be changed. This kindness is hugely powerful, and has the ability to save not just people who’ve suffered great hardship, but even a woman who has transformed into a totally different creature.

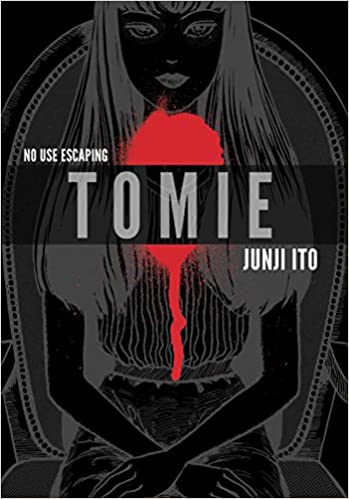

Special Prize: Tomie from Tomie by Junji Ito

Tomie, the creation of the horror-manga artist Junji Ito, is a beautiful young girl. All the men who look at her are taken prisoner, and find themselves overcome by an unbearable desire to kill her. And they do, in fact, kill her using a variety of cruel and gory methods (content warning: this manga really is very gruesome), but she doesn’t die. If her body is dismembered, she simply multiplies, with each part becoming a brand-new Tomie. She has regenerative power enough to survive even immersion in acid—indeed, whatever is done to her, Tomie has the power to stubbornly come back to life. She thinks of the men simply as tools that she can use, and loves only herself—to the extent there are sometimes death matches between different versions of herself: Tomie vs. Tomie.

What makes Tomie so unique is not only these powers of hers, but also the way she reveals her true nature from the get-go, swearing, being nasty to others, and remaining alarmingly faithful to her desires. For the people around her, it’s an absolute nightmare. And yet, the men fall head over heels for her, killing her so that she multiplies in number—this cycle is repeated endlessly. Tomie is a totally unique presence, and so true to herself that I can’t help admiring her.

The post Female Ghosts and Spirits from Japanese Folklore, Ranked appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : Female Ghosts and Spirits from Japanese Folklore, Ranked