When I was editing my debut novel, , a quote from Ilya Kaminsky’s poetry collection, Deaf Republic , kept me company. “The deaf don’t believe in silence,” he writes, “silence is the invention of hearing people.” The quote interested me in part because my book concerned Alexander Graham Bell, a man who is often romanticized as having conquered silence through inventing the telephone. Kaminsky’s quote also resonated with me because I grew up deaf, grappling daily with people’s habit of equating deafness with silence. Deafness was understood by the adults around me to mean a lack of sound, for which the remedy was amplification delivered via technology. As a result, I’ve spent my life lipreading and wearing hearing aids, living perpetually on the edge of the acoustic, hearing world.

, kept me company. “The deaf don’t believe in silence,” he writes, “silence is the invention of hearing people.” The quote interested me in part because my book concerned Alexander Graham Bell, a man who is often romanticized as having conquered silence through inventing the telephone. Kaminsky’s quote also resonated with me because I grew up deaf, grappling daily with people’s habit of equating deafness with silence. Deafness was understood by the adults around me to mean a lack of sound, for which the remedy was amplification delivered via technology. As a result, I’ve spent my life lipreading and wearing hearing aids, living perpetually on the edge of the acoustic, hearing world.

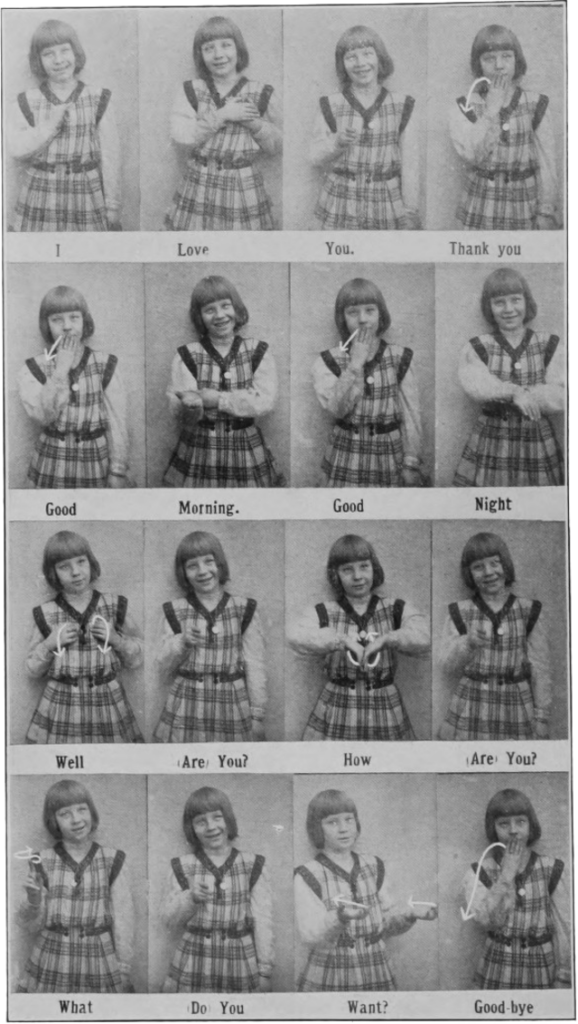

When I started learning British Sign Language as an adult, and ditched my hearing aids for periods of time, I didn’t find silence waiting for me. Instead, silence simply ceased to exist. As a deaf friend once told me, “Silence isn’t about noise or sound—it’s about absence of communication.” I tried to keep this in mind as I was writing my novel, to avoid any tendency to talk about my protagonist’s “silence.” Nonetheless the word crept into my writing. It was such easy shorthand for my protagonist’s experience in a world that is so wedded to sound. Just before I sent the final draft to my editors, I searched how many times the word “silence” appeared in the manuscript—15—and I checked each one. There was the physical quality of silence in relation to the telephone that wouldn’t work, or a broken piano. The silence of not being able to express one’s feelings. The silence of unnamed grief. And the silence of withheld information or communication, usually from the deaf protagonist. In a book about deaf people, this silence was particularly pertinent.

Ostensibly, Bell’s concerns were with communication, rather than silence. Both as an inventor of the telephone, and as an educator of deaf people, he focused on dispelling solitude, and bringing a connection into being. But he was prescriptive about the nature of that connection. His route was the human voice. He promoted speech training and discouraged the use of sign language amongst deaf people. His approach was known as oralism, and in the second half of the nineteenth century Bell saw himself as one in a small band of pioneers promoting oralist methods. At the start of writing the book, long before I came across Kaminsky’s poetry, I highlighted a quote of Bell’s: “Who can picture the isolation of their lives?” he said in a public address in 1887, before continuing, “[…what is] the solitude of an intellectual being in the midst of a crowd of happy beings with whom he can not communicate and who can not communicate with him.” Bell himself often cut a solitary figure: He went for long walks alone, even as a child, and spent hours on his own in his workshop, usually in the small hours of the night. His wife, Mabel, once gave him a painting of an owl—“a night owl”—to hang in his workshop. Mabel, who was deaf herself, was perpetually frustrated by her husband’s nocturnal schedule, so her gift may say more about Bell’s proneness to solitude than hers, and his particular point of sympathy for deaf people. But Bell’s error was to solely perceive deaf people’s solitude as their loneliness in the hearing world, where communication is primarily a vocal, audible act.

What Bell failed to realize, or chose not to see, was that for many deaf people, the nineteenth century was far from a time of solitude. The first school for deaf people in America was founded in 1817 by Laurent Clerc and Thomas Gallaudet in what has become an origin myth for the American Deaf community. In the U.K., where I’m from, numerous schools for deaf people opened across the country throughout the 1800s, as well as across Europe more widely. These schools primarily used signed languages as the language of instruction. This was a time of emergence for Deaf culture as deaf people came together, in large numbers, for the first time. As the century rolled on, Deaf churches, Deaf associations, and Deaf newspapers were founded. When I started researching A Sign of Her Own, I was fascinated by these networks and connections. The more I looked, the more instances I found. In 1886, for example, an amateur Deaf theater group in London staged a performance of Hamlet in sign language for an audience of 600. Bell himself learned some sign language when visiting the larger schools in the States, so he would have been aware of this growing sense of collective consciousness amongst deaf people. Nonetheless, he concluded that lipreading and speech were the preferred routes for the deaf child.

Bell’s concerns about deaf people’s education reflect mainstream anxieties emerging in the second half of the century. Some of these anxieties can be seen as a reaction to deaf people’s lack of solitude; in their preference to associate with each other. In the States, deaf people’s “difference” became embroiled in alarmist views over a perceived increase in immigration and what this meant for national culture and identity. Anxieties also arose in light of Darwin’s new theory of evolution, and what distinguished humans from primates. In an era increasingly concerned with progress, the oralists decreed speech to be the chief attainment of human evolution. Bell was also interested in the early eugenics of the time and wrote a paper warning that deaf people’s association with each other would lead to a “deaf race.” Though he later backtracked on some of his public recommendations that deaf people shouldn’t intermarry, he remained involved in eugenics committees and continued to campaign for speech training as the route by which deaf people would learn to socialize with hearing people, meaning they would be less likely to associate with one another.

Through Bell, a huge breakthrough in telecommunications was twinned with a swiftly gathering campaign for oralism and the suppression of sign language. For deaf people, the culmination of this turning point in Deaf history is often marked by the Milan Conference in 1880. At this event a group of over 160 hearing delegates, and one deaf delegate, debated the superiority of using speech versus sign language in educational settings. The result was a resolution banning the use of sign language in schools. It was a recommendation rather than an enforceable ban, but it was widely adopted by schools, especially in the U.K. and continental Europe. While Bell seems to have been unable to attend this particular conference, he supported its aims and fought for the oralists’ campaign. The impact was devastating for deaf teachers who lost their jobs and were replaced by hearing teachers; it was also devastating for many profoundly deaf children who grew up without adequate access to a language—either English or sign language—as a result. In the U.K., Dr. Reuben Conrad published a report in 1979 showing the language deprivation which resulted from a century of oralism. The median reading age for deaf school leavers was nine years old. Many profoundly deaf school leavers struggled with even basic literacy.

It isn’t possible here to cover all the developments of the twentieth century in deaf education. The debate over using signed languages in the classroom continues, entwined with the role of technology. But in an important way, Bell failed in his ambitions. The Deaf community has remained strong, although in the U.K. at least, new challenges have arisen through the closure of so many schools for deaf people and Deaf clubs in a drive to bring deaf students into mainstream education. There has also been increased recognition for signed languages across the word. Groundbreaking work by American linguist William Stokoe in the sixties, and deaf campaigners—such as the sign language poet Dot Miles—have elevated the status of signed languages and helped ensure their recognition as true languages. After a long campaign by the Deaf community, British Sign Language was finally granted recognition as being its own language in 2003 and legal recognition as an official language of the U.K. in 2022. Representation in mainstream media is starting to improve, and Deaf art—especially Deaf theater—is flourishing. But deaf and hard of hearing people, including myself, continue to struggle to have basic access needs met in a world where most people are happy to assume that sound is an essential, inevitable—and even superior—feature of our human landscape. Progress is patchy, and often not where you would most hope to find it.

For me, deafness has been a personal journey. It has been helpful to think about deafness not as a silence, but as a rich experience, one that is bound with the particularities of my audiogram, background, race and class. Deaf experience is incredibly varied. Being able to define deafness for myself has been important in embracing it and dealing with the barriers that arise in society. In writing A Sign of Her Own I’ve tried to understand how deaf people in the nineteenth century—and beyond—have been trapped not by silence, but the ways in which silence is invented for them. As the deaf protagonist notes in A Sign Of Her Own, when one of the hearing characters is attempting to listen through a closed door behind which two people are signing together, and hearing nothing—this silence was “the richest talking of all.”

The post Deafness Is Not a Silence: <br>On the Suppression of Sign Language appeared first on The Millions.

Source : Deafness Is Not a Silence: On the Suppression of Sign Language