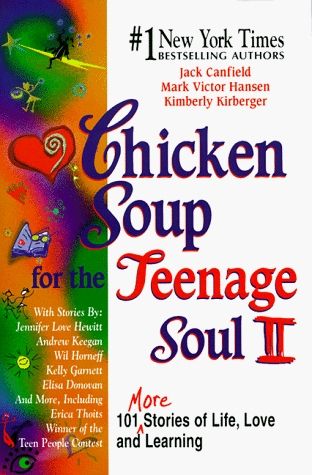

My parents recently moved across Canada to Vancouver, which is where I’ve been living for the past six years. With them came a box full of my childhood report cards, letters, cards, graduation certificates, and swimming badges. Reading these was like attending a reunion with my childhood self, and among those momentos I came across the acceptance letter and contract from when I was published in Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul 2. I was 13 when I submitted my story to them and 15 by the time it was published, and the acceptance letter was definitely the most exciting mail I’d ever received. I’d basically be famous, my name listed alongside celebs like Jennifer Love Hewitt and Andrew Keegan — it was 1998, clearly.

I’d discovered the original Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul in a Boca Raton Target, and reading the plethora of teen-penned stories felt like the first time people were writing about relatable experiences. Not only that, but when I discovered they were looking for stories for a second book, it felt attainable. I’d been writing short stories and poems for years and this book was filled with stories that mine could blend in with.

And so I wrote a semi-autobiographical, banter-filled take on a teen’s unrequited crush, Buffy references and self-deprecation abounded. I didn’t realize that the stories were meant to be totally true and, frankly, mine was not. It was an imaginary conversation between imaginary people but based on real people and thoughts. And yet, as I received emails from teens who had read and related to my story, I realized with shock that teens were reading this book in droves. Teens from all over the world, of varying ages and experiences, all yearning to see themselves in the pages of a book.

Niche Interests

And that was the gimmick of the Chicken Soup series. Creators Jack Canfield and Mark Victor Hansen had a knack for finding a niche and digging into it. You a fan of golf? Well, grab a copy of Chicken Soup for the Golfer’s Soul. Teachers, Coffee Aficionados, Cat and Dog Lovers? All get their own collections.

Part of the draw is how each title is based on a niche aspect of your identity — be it interest, religion, or race — and that turns the books into easy gifts. As long as you knew a person on a semi-basic level, you can find a compilation that’ll fit.

Unless, of course, you were looking for an LGBTQ+ story focused Chicken Soup, which still doesn’t exist 29 years on. The brand website’s About Us copy makes sure to give LGBTQ+ readers some hope, writing “[t]he members of our team are diverse, representing many ethnicities, religions, nationalities, and the LGBTQ community. We continue to seek even more diversity in our team members and our storytelling as we further our mission of ‘changing the world one story at a time®.’”

Hmm.

Their recent publications seemingly have a religious bent; 2022 gave us Miracles and the Unexplainable, Believe in Angels, The Magic of Christmas, and Devotional Stories for Mothers and Grandmothers. It’s a whole mood, although current Editor-in-Chief Amy Newmark has denied that Chicken Soup has any such religious agenda. Newmark addressed this in a Vice article by Diana Tourjée, saying “We don’t know how we ever got the reputation for being a Christian publishing company, as we have never been that.”

In 2014, Katy Waldman wrote an excellent critical analysis, summing up Chicken Soup’s Newmark-era content shift with a wry but apt description: “Originally an all-purpose mix of entertainment and inspiration, the franchise has reinvented itself in part as a source of celestially-bathed lifehacks.”

The brand doesn’t just put out books anymore. The company has produced a podcast, a socio-emotional learning curriculum, children’s books, a video-on-demand network called Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment, pasta sauces, puzzles, and, last but most certainly not least, a line of pet food products. So how did this multi-product empire first come to be?

Origin story

|

|

Canfield and Hansen were successful motivational speakers before they began working on their first Chicken Soup for the Soul. According to Cynthia Gorney’s history of the franchise, written for The New Yorker in 2003, Canfield was the original creator. His early career included teaching high school, co-founding a humanistic-psychology center in Massachusetts, co-writing a children’s self-esteem workbook, and founding Self-Esteem Seminars, where he told short, inspirational stories aimed at bolstering people’s confidence.

In 1992, he enlisted Hansen as co-editor, with the plan to compile a book made up of the sorts of motivational stories Canfield had become famous for telling. They put together a chapter and found an agent, Jeffrey Herman, but Herman struggled to get a green light. Publisher Ron Fry related to Gorney that he found the first chapter to be “[k]ind of treacly.” On top of its unproven potential, Hansen and Canfield wanted a $1500 advance for it.

Canfield and Hansen would not be deterred. Gorney explains that the co-authors wanted to reach people who didn’t identify as book readers and who might not purposefully walk into bookshops to browse. Their small team, also consisting of Patty Aubery, whose job was as sort of a jack-of-all-trades-meets-office-admin. Gas stations, nail salons, flea markets, PTA meetings, self-help seminars…the co-authors and Aubery hustled to get the books into the hands of the public. And it worked.

At the back of the book, the co-authors invited their readers to contribute to the next volume by suggesting they “[s]hare your heart with the rest of the world.” As Gorney points out, the fact that the books took stories from readers was another draw for the public at large. Gorney writes, “As it happens, very few places exist these days in which an ordinary person without a literary agent might hope to share her heart with the rest of the world. There are a few magazines that publish first-person accounts, and there is of course the internet, which was still on training wheels when the first Chicken book came out.”

That was part of what drove me to submit, though it was less sharing my heart and more sharing my words. I’d fancied myself a writer since I was 8 or 9, and when I spotted the invitation to submit at the back of the book, it felt like this was my moment. Some of the stories were more emotional than skillful in their narratives; if they could be published, then I had a chance. I’d imagine many burgeoning writers felt the same.

In 2008, Canfield and Hansen sold Chicken Soup to a new ownership group, one managed by Bill Rouhana and Bob Jacobs. That is when Newmark, Rouhana’s wife, first came into the picture. Between 2008-2014, Newmark, Canfield, and Hansen began co-editing the books together; eventually, Newmark would edit on her own or with guest co-editors. Rouhana and Jacobs wanted to bolster the popularity of the books while also branching out into licensing products in adjacent fields — pet food for all the animal lovers reading their books, for instance. In an interview with Forbes in 2011, Rouhana and Jacobs extolled that the Chicken Soup brand stood for “hope, faith. and trust.” You can see that branding in the books’ current iteration as overseen by Newmark; faith, hope, and trust could literally be the subtitle of many of their more recent collections.

SHARING IS CARING

|

By the time Chicken Soup for Teenage Soul 2 was published, I was 15. Raised on the self-deprecation and skepticism of sitcom humour and Buffy, reading saccharine stories about teenagers problems had become far less appealing.

I received my free copy and, delighted to be published and paid, cracked open its hardcover spine and began to read my story, titled “Unrequired Love.” With growing annoyance, I noted the editor’s choice of beginning my story with a Charlie Brown quote and altering its final line. I didn’t really recognize the characters in the book anymore either; a lot had changed for me between 13 and 15. Then, when done, I closed the book and laughed, oh how I laughed, before getting up and sliding the copy onto my bookshelf. Nestled amongst book faves like Please Kill Me: An Oral History of Punk Rock and The Picture of Dorian Gray, I did not open Teenage Soul 2’s pages again for many years.

While I haven’t read any other books in the franchise since and don’t ever plan to, it doesn’t mean I think they are without merit. Yes, Chicken Soup can be preachy and cheesy, but it did normalize the practice of publishing stories by everyday people — even giving a voice to many who felt their stories might not otherwise seem worth listening to.

Teenage Soul 2’s stories didn’t bolster my self-esteem, but being published made a difference. That’s one thing I’d genuinely compliment about the franchise: its willingness to listen to its readers’ wants. As Waldman explains of the books’ appeal, their can-do attitude and uplifting platitudes will fill some readers with a sense of healing and hope that is able to battle even the wryest cynicism. Towards the end of her article, Waldman writes, “‘Chicken Soup is the worst,’ I told my roommate, flinging down the book. What I didn’t say was that I’d been reading for an hour and I’d already cried three times.”

Maybe that’s what Canfield and Hensen really figured out with the formula — there are a lot of people out there who just want to have a cathartic cry while reading a book that seems to almost actively care about their interests, happiness, and self-improvement.

Weird angel fixation or not, have at it, I guess.

Source : Chicken Soup for the Soul: Publishing Everyday Stories