Content Warning: This post contains foul language, as well as discussion of online harassment, depression, and suicide.

I’m currently about a third of the way through The Name of the Wind, the first book in Patrick Rothfuss’s Kingkiller Chronicle trilogy. It’s one of my partner’s favorites, and I’ve got plenty of time right now to dive into a 600-plus page fantasy book. I’ve been enjoying it so far, but I recently made the mistake of logging onto my favorite least-favorite website, Goodreads, to check on the status of the series’s third installment, The Doors of Stone.

If you’re familiar with Pat Rothfuss, the seemingly endless delays behind The Doors of Stone, and the general…culture of Goodreads comments, you probably know where this is going. But if not, if you’re a normal, well-adjusted person who isn’t Too Online like me, and you don’t possess this unfortunate curiosity that compels you to enmesh yourself in a search for context and meaning for every piece of internet drama you come across, here’s a summary.

The Name of the Wind was published in 2007, and quickly became a sensation among fantasy readers. It won the 2007 Quill Award. It received glowing blurbs from George R.R. Martin, Ursula K. Le Guin, Terry Brooks, Robin Hobb, and others, in addition to being pretty well-received by critics. Its sequel was published in 2011 and topped The New York Times fantasy list. All along the way, Rothfuss and his ongoing trilogy garnered a considerable fan base of readers who were eager and excited to see how the story concluded, even if there was to be another five-year gap before the third book dropped.

Well, five years passed pretty quickly, and The Doors of Stone was nowhere to be seen. Rothfuss, on the other hand, had an increasingly public profile, with the aforementioned appearances at conferences, Twitch, and YouTube channels, a podcast, and a generally active online presence. As the author engaged in a more public persona, more time passed, and as of writing, it’s been nine years since The Wise Man’s Fear, and the third installment of the Kingkiller Chronicle has not yet been released.

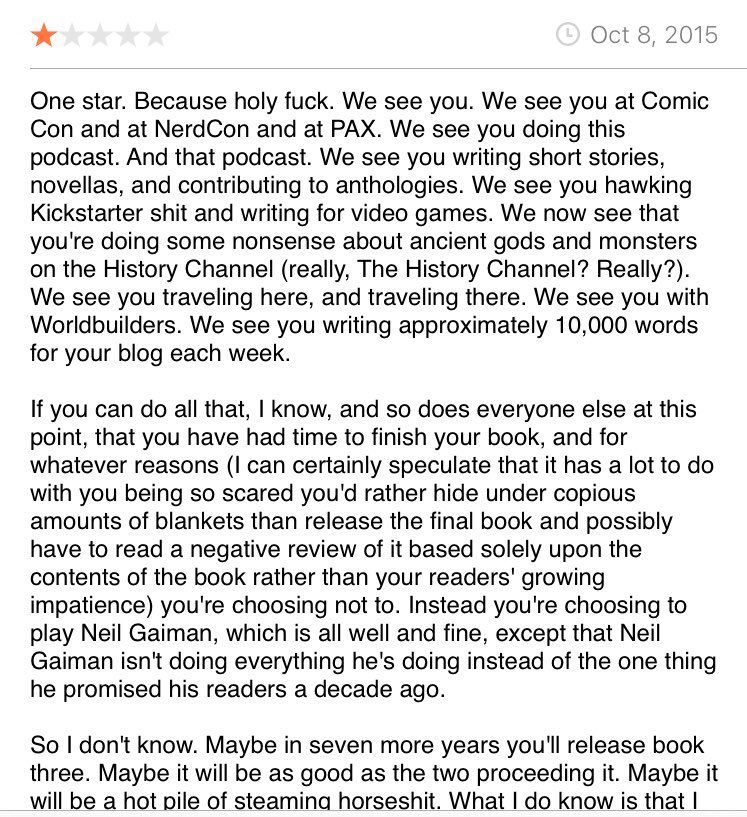

Certain factions of Rothfuss’s fandom have become vocal about the long stretch of time between books. As with anything, there’s a gradient to their anger, ranging from more or less polite declarations of disappointment, to the outright toxic, such as the screenshot above. Here are some other pulls from the Goodreads page for The Doors of Stone:

- “This is crap. For waiting this long, I’m pirating the damn book from online if it ever comes out. I’m not giving you my money again.”

- “[M]y advice is to give up on this author since he doesn’t seem to care about his readers.”

- “So my new policy: NEVER start reading a fantasy series unless all the books are out. Fantasy authors are demons who are put on this earth to crush your soul and suck the life out of you while you wait endless years for the next installment. “

- “Sadly, I would discourage anyone from reading this series, for the sole reason that I no longer believe it will ever be finished.”

- “Just fuck off, Rothfuss. Seriously. Fuck off.”

Although varying in levels of anger and profanity, the negative comments on The Doors of Stone all seem to express one in thing in common: the book is taking too long.

Aside from Rothfuss’s other public interests that readers perceive as getting in the way of his writing, the other most commonly cited grievance is the claim Rothfuss made that all three books in the series were finished at the time of the first’s publication—a grievance that, to me, betrays a lack of understanding of the creative and publishing processes. (Although, I guess it shouldn’t surprise me if the authors of passionately meandering Goodreads comments aren’t familiar with the concept of editing.)

It may very well be true that the entire Kingkiller Chronicle was complete upon the initial publication. But if so, that would mean Rothfuss was sitting on three very lengthy manuscripts that had not yet been edited either as individual texts, or pieces of a greater whole. Anyone who has written something, be it a long-running fantasy trilogy or just an essay for school, should know that writing the thing is only half the battle. After the creative juices have slopped themselves upon the page, the actual work of codifying your writing into something coherent and satisfying begins.

Editing is the larger, more significant hurdle. Everything you’ve ever read that was worth the effort (and, realistically, even a lot of what you’ve read that wasn’t) went through a some kind of editing process to make sure it was in its best possible form. The complaint that the trilogy should be complete by now simply because Rothfuss already has a draft of it disregards the fact that, even if such a draft exists, it is, for one reason or another, not ready to be published. I can’t help but wonder how many of the same people harassing the author that the book is taking too long would have done the same had the final installment been substandard.

However, the alleged existence of a draft for The Doors of Stone is almost completely beside the point. The bigger grievance I have with the people demanding the third Kingkiller book is their entitlement to the author’s time and energy.

As you’ve seen in the comments selected (and which you would continue to see in abundance if you were to be so foolish as I am to peruse the Goodreads page yourself), many of Rothfuss’s readers are angry. They’re not only angry at the lack of third book, but also angry at his YouTube channel. They’re angry he makes appearances at PAX and Comic Con. They’re angry he plays video games. They’re angry that he maintains an active blog. In short, they’re angry that he isn’t writing enough, and some cases angry that he isn’t writing enough of the specific thing they expect him to write.

We must ask ourselves: what authority does anyone have over how Patrick Rothfuss spends his time other than Patrick Rothfuss?

If Rothfuss never writes another word of any book ever again and instead decides to become, I don’t know, a full-time podcaster, why does any one of his readers get to decide that’s wrong? While you’d certainly be entitled to your disappointment that the Kingkiller Chronicle will remain unfinished, does not getting to read a book really entitle you to tell its author to fuck off?

I’m not going to defend Pat Rothfuss as a human being, nor the content of his character. I don’t know him as a person, and as such am not qualified to make any sort of judgement about him or his work ethic. What I do feel qualified to comment upon is the nature of fandom.

The access to our favorite creators that the internet affords us has instilled an expectation of said access—a truly awful feedback loop of entitlement and agitation. Such agitation is borne of when our favorite creators don’t perform to our standards. Content creators, including authors, have to in some way commodify their humanity in order to reach and satisfy their audience.

Everyone on the internet, from famous and successful artists to your weird uncle on Facebook, makes content of their personalities in this way. We are each performing a version of our personalities whenever we post something. You do it when you share pieces of your day on your Instagram story. Your weird uncle does it in his colorful rants about cancel culture. I’m doing it right now, in the form of this post on BookRiot.com.

No matter how smart and compartmentalized you believe your relationship is with the media you consume, there is no escaping the fact that the core essence of our digital and social media is predicated on this idea of access, and wherever there is access, so too will you find entitlement. Maybe someone who usually posts memes suddenly has a political take you disagree with. Maybe the comedy songwriter posts their serious music and you feel weird even giving it a chance. Maybe the fantasy author whose books you adore is spending what you think is too much time on Twitch playing Minecraft.

I don’t believe people are wrong to be disappointed in the long wait between Kingkiller books. Nor do I think you have to support every last endeavor your favorite content creator embarks upon. I’d even go as far as to say there are tangible benefits to allowing consumers such direct access to who and what they choose to support with their time and money. At its worst, though, this model breeds a combination, of entitlement-via-access and the agitation caused by personalities not meeting our expectations, that becomes an often toxic cocktail.

On his otherwise cheery and irreverent blog, Rothfuss has occasionally posted about his depression. Again, I don’t know him as a human being, but it is not too much of a stretch to wonder in what way the pressure of appeasing an often thankless fanbase can interact with extant mental illness.

We’ve seen evidence of the toll trying to satisfy fans can take on creators. I think of Travis McElroy’s anxiety surrounding reactions to the newest campaign of The Adventure Zone, or the tragic passing of professional wrestler Hana Kimura, who died by suicide after the online harassment she endured became too damaging and all-consuming, or Twitch streamers who feel psychological pressure to stream every day, as not sticking to their schedule will cost them fans, ergo costing them money, because of an expectation placed on them to ceaselessly contribute to digital scrolls of infinite stimulation.

Fandom can be insidious. The stresses of being a content creator can unravel your very sense of humanity, because modern artistry is almost always a game of selling yourself as a brand. In fact, even deliberately choosing not to engage with the online circus, even holing yourself away and writing books and not making public appearances—a privilege that fewer and fewer authors get to enjoy—is itself a brand. As a culture, we have demanded access and product to the point of painting ourselves into a corner, from where we, ironically, lack access to our most basic sense of empathy for the people who entertain us.

I don’t mean to get too “oh, woe is the wealthy content creators” on you. I’m sure Patrick Rothfuss is doing fine. It’s important to remember that making art for a living is a privilege, one not everyone is lucky enough to even come close to doing. That being said, even the most privileged people are still people.

Being a fan of things is great. It provides reliability and comfort to our otherwise hectic, even banal lives. But the next time you feel agitated because the next installment of something you enjoy is late, or one of your favorite content creators is doing something other than making content for you, I urge you to remember the human on the other side of the transaction. I urge you to remember that creators don’t owe fealty to your expectations, and I urge you to remember authors don’t owe you books.

Source : Authors Don’t Owe You Books