Ask the average person what a comic book is, and they may describe a bit of fluffy nonsense in which a leotard-wearing man punches another leotard-wearing man. Kid stuff, in other words. Cheap. Uncreative. Not worthy of an adult’s time. Any adult who admits to liking comics must therefore be a virginal loser who still lives with his mother, which is obviously a bad thing. (Thanks for nothing, The Big Bang Theory.) While the success of various superhero movie franchises has dispelled a bit of the stigma, it’s certainly still around.

These assumptions are based on a number of factual errors, the most serious of which is that comic books are exclusively for children. This is not and never has been the case. It is true, however, that the perception of comic books being exclusively for children has gotten the industry in a lot of trouble and continues to determine how people view the medium. Hopefully, this article will provide a more complete perspective on who comics are intended for, who actually reads them, and why the fun police can take a hike.

Note: Although I’m arguing that comics are not exclusively children’s books, that doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with children’s books. Even if all comics ever made were “just” for kids, they wouldn’t deserve the ire and dismissiveness so often directed at them. Kids’ books are just as valid and valuable as any other type of literature and should be respected as such.

The Golden Age (1938-1956)

(This section and the next owe a great debt to David Hajdu’s book The Ten-Cent Plague. I strongly recommend it if you want a more thorough examination of the topics discussed here.)

Comics as we know them began as collections of newspaper strips. They didn’t grow into their own until the invention of superheroes, starting with Superman’s 1938 introduction in Action Comics #1. These comics were cheap and, like news strips before them, thought to appeal only to children and lower-class (often immigrant) adults who couldn’t understand “real” literature.

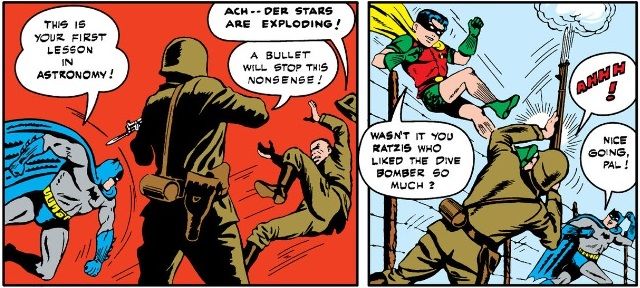

Even at this early date, however, it was clear that comics had a broader appeal. During World War II, comics accounted for a quarter of all magazines shipped to American soldiers overseas, according to Bradford W. Wright’s Comic Book Nation. Granted, this might be partly due to wartime propaganda: just about every comic book character from Batman to Sheena the Jungle Queen had taken up Nazi punching. But the point remains that both the soldiers and the people responsible for stocking their care packages acknowledged that comic books had value for adults. Comic book creators must have been aware of this, especially given the number of creators who joined the military, so I can’t imagine that they weren’t working just as much for the soldiers as they were for the kids.

Naturally, some killjoys took exception to American soldiers’ love of such “childish” entertainment. And when it comes to children’s books, adults inevitably want to assert authority and make sure there’s nothing there that could upset or “damage” fragile young minds. As early as 1942, Sensation Comics — published by All-American Comics and starring Wonder Woman — ended up on Catholic banned books lists. Over the next decade, the anti-comics movement slowly picked up steam, fueled by hyperbolic claims that comic book violence led to real violence. Just about every kid in America read comics at this point, so they might as well have blamed juvenile delinquency on ice cream and tried to exile the Good Humor man.

It’s important to define the term “comic book” here. While comics are now largely equated with superheroes (in the U.S., anyway), comics encompassed (and still encompass) a wide variety of genres. Some of them, like Disney comics and adaptations of literary classics, were above suspicion: these were deemed “wholesome” enough to escape religious and political wrath.

Most other genres were not so lucky. Superhero comics were at the eye of the moral hurricane, accused of everything from fascism to homosexuality to — gasp! — being unfeminine. Teen comics, too, took their share of licks. Even Archie, which until recently was regarded as the most inane comic in existence, was criticized for being too horny. Crime comics were also targets, for obvious reasons.

And then there were the horror comics. Hoo boy, those horror comics.

EC Comics (the EC stands for “educational comics”) didn’t publish just horror comics, but that’s what they’re best remembered for, mainly because that’s what caused their downfall in the mid-1950s. Lurid images from books like Tales of the Crypt and The Vault of Horror were shown in Congress as definitive proof that comic books were inappropriate for children. These congressional hearings led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority, a self-governing censorship bureau that spelled doom for EC Comics and innumerable other publishers.

The Silver Age (1956-1970)

Whether or not we agree with Congress’s accusations (while a lot of them are obviously BS, I have read some of EC’s material and that stuff needs a warning label at least) is not the point. Those hearings, and the comics backlash in general, would not have happened if comics were not widely perceived as children’s books.

But even at the height of anti-comics sentiment, not all comics were aimed at children. Romance comics, for instance, were explicitly marketed to older teenagers. One such comic, Young Romance, was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, two of the earliest industry giants and co-creators of Captain America. As the kids who grew up reading superhero comics entered the comics industry themselves, they began to add a more sophisticated touch to the medium.

I’ve discussed elsewhere the ways in which comics clumsily crawled toward more serious stories, so I won’t go over it all again here. Instead, let’s talk about Roy Thomas. Thomas, who would succeed Stan Lee as Marvel Comics’ editor-in-chief, brought unprecedented maturity and continuity to the material, indicating a new level of respect for the audience’s intelligence. His small footnotes (something along the lines of “Thor isn’t in this issue of The Avengers because he’s busy in his own mag! Check it out!”) gradually mutated into the frequent crossovers and sprawling, shared universes that made things like the Marvel Cinematic Universe possible (and that children and adults alike may find intimidating).

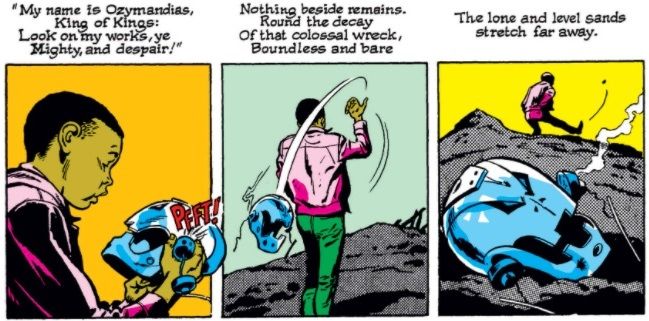

Thomas also liked to infuse his work with literary references. To give just one example, he ends Avengers #57 with a page-long recitation of Percy Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” You don’t quote sonnets if your only audience is 6- and 7-year-olds.

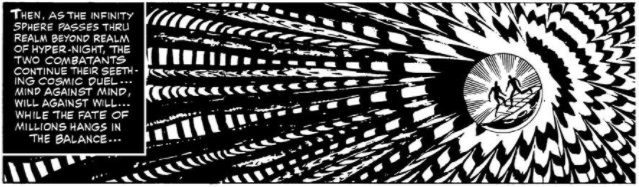

Thomas wasn’t the only one experimenting with the medium, either. Artists like Jim Steranko and Jack Kirby were creating some wild panels in books like Strange Tales and (of all things) Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen, respectively. Check out this psychedelic panel from Strange Tales #167.

You can also gauge the maturity of the audience at this time by the letter pages, where the creators print and respond to fan mail. I don’t mean maturity in terms of age, necessarily (writers’ ages are rarely included), but after looking through the letter pages of some issues I selected from my own collection — Batman #150 (1962), Teen Titans #4 (1966), and Batman #200 (1968) — I could tell they weren’t kids only interested in bright colors and fisticuffs. Whatever their ages, they were itemizing parts they liked, complaining about “ridiculous” stories, and pointing out potential plot holes. Even in the ’60s, one of comics’ goofiest decades, fans were old enough to engage with and think critically about what they were reading.

The Bronze Age (1970-1984) and the Modern Age (1984-Present)

Comics continued to get darker and more “adult” over the ensuing decades. I don’t just mean superhero comics: the success of nonfiction books like Maus and Persepolis helped convince more and more people that comic books were no longer just for kids — even though, as I’ve already shown, they never had been. The emergence of scholarship surrounding comics, as evidenced by the books I’ve cited in this article, further demonstrates the medium’s appeal not just to adults generally, but to adults who take it seriously as both art and literature. And yet, the idea that comics are only for kids refuses to die, even among some who worked on them for decades.

Alan Moore helped popularize (however inadvertently) dark, ultra-violent, definitely-not-for-kids comics through his work on, among other things, Watchmen. He has since disowned his own comics, which he talks about in this interview from October 2020. I disagree with a lot of what he says here: he dismisses superheroes as “children’s entertainment,” and claims that adults who like superhero films — which he decries as worthless “escapism” despite admitting he hasn’t watched any since 1989 — just want to “go back to a nostalgic, remembered childhood.”

This is all very pretentious and patronizing, but there is a fair point to be made about the role childhood nostalgia plays in driving modern superhero stories. A 2017 report showed that most people who buy superhero comics are male, and about half of them are between 30 and 50 years old. These older, male readers are far more likely to do their buying in a comic book shop versus a bookstore or online. And unfortunately, when the comic book industry measures comic sales, they focus on sales of single issues — the kind people buy at comic book shops — and exclude digital issues or collected issues sold in bookstores.

Needless to say, prioritizing nostalgia over reality can get you in trouble, as several Marvel executives found out. In 2018, the internet busted Marvel for misinterpreting its own sales figures in order to claim that diverse titles don’t sell. (This despite the fact that Ms. Marvel, the groundbreaking book starring Marvel’s first major Muslim superhero, was a New York Times bestseller!) “Diverse” titles, AKA those starring female heroes or heroes of color, tend to feature newer characters who were not around when the single-issue buyers were children. These titles sell quite well if you actually take all the data into account, which Marvel (and, one assumes, DC) does not.

In other words, the success of a superhero comic is judged only by its success with older male audiences — with men fueled by their nostalgic love of Batman and Spider-Man — rather than all buyers. In this sense, superhero comics aren’t for children; they are for people who were once children and prefer (understandably, in some ways) to stick with what they know.

Despite this relentless pandering to one very specific, adult audience, you can still find plenty of superhero comics for kids. In fact, they are often explicitly marketed as such. Franchises like Marvel Adventures and DC Super Hero Girls, for instance, state in marketing copy that they are perfect for “all ages” or “young readers” — a designation that would not be necessary if comics were inherently a children’s medium.

Be a Hero: Let People Read What They Like

While I’ve mostly talked about superhero comics here, other genres of comics certainly still exist, for kids and adults alike. I haven’t even touched on manga, which, according to the 2017 report, is very popular with teens and young adults. (It’s difficult to tell from sales numbers how many kids are reading a given comic, since their parents are probably doing the actual buying.)

In closing, comic books may look different from other forms of literature, but they are just as diverse and cater to just as many tastes and demographics. I believe the real problem here is not that people think comics are for children. Rather, they think comics are childish. All those big pictures and funny outfits, and so few words: how could a grown-up take such a thing seriously? Clearly, the only appropriate response when someone likes “childish” things is to insult them and try to take away what they love while acting superior for liking the “right” things.

In the end, it shouldn’t matter if comic books are — or are perceived to be — for children, or for adults nostalgic for childhood. What really counts is that you enjoy what you read. No one else can or should take your reading joy from you, whether you like Percy Shelley or comic books about men in leotards punching each other — or both.

Source : Are Comics for Kids or Aren’t They?