I was proud of the literature published and celebrated this year. It is always hard to choose, but especially at a time like now, when there are so many rich, nuanced, and courageous stories being told, when no single perspective is monopolizing the narrative. Still, these are just a few of the many books that filled me with hope.

I don’t usually read short story collections front to back, but Alexia Arthurs’s How to Love a Jamaican is exceptional. My favorite story is about a twin who, after a sighting of his estranged brother, reflects on their charged relationship, but I was enthralled by all of these complex and insightful celebrations of Jamaicans, at home and abroad, making their ways while mindful of the weight of history on their back.

I read Criminals, an older book by Margot Livesey, on a plane home from the Texas Book Festival. I finished it before I landed. In the first scene, a man finds a baby in a bathroom and takes her to his sister’s house, and so begins this suspenseful yet complex depiction of what people need, what drives people to do the things they do, and how far people will go.

I always return to Edith Wharton’s Ethan Frome. I read it for the first time in high school, and now it’s like eating my Auntie Ann’s potato salad; when I start the first page, I’m taken back home. There aren’t too many books that control the reader the way that one does, that upends expectations and manipulates emotions, and by the end, even though I know what’s coming, I always feel haunted for days.

Heads of the Colored People is a hilarious and fresh reflection on race inequality. The characters are portrayed wholly and insightfully, and their experiences are masterfully conveyed. I will read anything Nafissa Thompson-Spires writes.

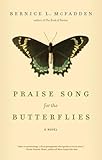

I read so that I can be transported and Praise Song for the Butterflies does just that. Bernice McFadden can inhabit any culture, any character, any experience, and Praise Song for the Butterflies is no exception. For those hours I was with Abeo, a daughter sacrificed to a religious sect, the burdens of her heart were mine.

I haven’t read a memoir like Heavy before. Kiese Laymon’s childhood experiences were textured and painful, and yet he managed to render them in such a way that their depth was not lost in the process of sharing them with us. I can’t imagine how much work it took, but the book reads as effortless—that’s how much grace each page carries. It’s a book to read, then reread, then reread again, and even then I don’t think we’d be capturing everything Laymon put down.

More from A Year in Reading 2018

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The post A Year in Reading: Margaret Wilkerson Sexton appeared first on The Millions.