This year, through no initiative or orchestration of my own, I read in twos. I realize this only now, picking out from a hasty reading ledger those books I liked or kept thinking about, and it’s not like I read the twos consecutively, more that little symmetries keep making themselves known as I look back, titles pairing off into smaller dialogues, gonzo breakout sessions with improvised themes. I didn’t read more this year but I read longer, with a better attention span, this being the first year in almost 10 that I read more to read than to keep up with publishing, so maybe this is always happening and I just started noticing. I also have a brain that’s unrepentantly hungry for patterns, so who knows.

But for instance: the bookends of my reading year were the former is a book of fucking poems, orderly and solemn and very robustly beautiful without any undue ornateness. Brown is formally exacting, yet the depth of feeling in his poems is breathtaking, at times literally; they’re at once messy, wounded and lusty and scared and prideful, and sublimely still, composed. Nealon is an anarchic writer-thinker flirting with the politics of anarchism, but I find a fully formed existential moment in his “tepid intellectual watchfulness,” as he puts it, a visceral anxiety no less visceral for the fact that his only move is to articulate it, piecemeal. Both feel something’s not right in the present, know some things have been profoundly wrong for a long time, and though they sense this at different distances from their lives and bodies they inhabit it equally fully, make it equally person-sized and real. Also The Tradition debuts a fixed form Brown calls the duplex, and it is perfect.

The Organs of Sense is the first novel and second dazzling book by Adam Ehrlich Sachs, a teutonically involuted, toweringly philosophical novel that is by some weird alchemy more fun for being teutonically involuted and toweringly philosophical. It pulls you painstakingly along into a telescoping nest of relations of conversations of recollections of revelations of remarkable psychological extravagance, and all the while the story—Leibniz goes in 1666 to visit an eyeless astronomer, is the elevator pitch—is so engaging and fanciful and sweet, and Sachs’s comic timing so dead-on, that all you see is the timeless folly of people being people. It’s like Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine in that respect, except where that novel burrows deep into a single instant this one expands outward into the cosmos, or a seventeenth-century conception of it. I found The Organs of Sense paired well with Mike McCormack’s Solar Bones, published in 2017, another engrossingly human tableau bound in a vaguely forbidding formal armature. (Oh! Telescoping. Just got that. You win again, Sachs.) The armature in this case is a staccato accumulation of run-on monologues that dilate breathlessly on the smallest sensory minutiae; the book’s magic is that this makes it thrillingly lifelike, thrillingly like life uninterrupted, somehow like swimming in a bloodstream. My grandmother, who as a rule brooks no experimentalist literary impulse, told me weeks after reading it that she was still thinking about the one passage that’s like ten pages of disquisition about pouring concrete.

The Organs of Sense is the first novel and second dazzling book by Adam Ehrlich Sachs, a teutonically involuted, toweringly philosophical novel that is by some weird alchemy more fun for being teutonically involuted and toweringly philosophical. It pulls you painstakingly along into a telescoping nest of relations of conversations of recollections of revelations of remarkable psychological extravagance, and all the while the story—Leibniz goes in 1666 to visit an eyeless astronomer, is the elevator pitch—is so engaging and fanciful and sweet, and Sachs’s comic timing so dead-on, that all you see is the timeless folly of people being people. It’s like Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine in that respect, except where that novel burrows deep into a single instant this one expands outward into the cosmos, or a seventeenth-century conception of it. I found The Organs of Sense paired well with Mike McCormack’s Solar Bones, published in 2017, another engrossingly human tableau bound in a vaguely forbidding formal armature. (Oh! Telescoping. Just got that. You win again, Sachs.) The armature in this case is a staccato accumulation of run-on monologues that dilate breathlessly on the smallest sensory minutiae; the book’s magic is that this makes it thrillingly lifelike, thrillingly like life uninterrupted, somehow like swimming in a bloodstream. My grandmother, who as a rule brooks no experimentalist literary impulse, told me weeks after reading it that she was still thinking about the one passage that’s like ten pages of disquisition about pouring concrete.

Nina Leger’s Mise en pieces is a patient, thoughtful novel about a woman named Jeanne who keeps a memory palace of strangers’ dicks. The title (cleverly translated by Laura Francis as The Collection) means to cut into pieces but also to install in rooms, as art in a museum, and Leger writes with a kind of curatorial dispassion—but what she puts on display is the received logic of The Novel, structurally and sexually, dissecting and redistributing it into bigger or smaller boxes, objectifying it in the very way we were expecting it to objectify Jeanne. It’s brilliantly subversive but always more curious than militant.

I also read a lot of Valérie Mréjen this year, in unwitting anticipation of her English debut, Black Forest in Katie Shireen Assef’s translation. The first thing I sat down with was Liste rose, a series of personal ads assembled from names cut out of a phone book, which turned out to be a good model for the way she works: even in more direct forms of storytelling—about a non-start romance, for instance, or about parents and children—her method is decoupage, fragmentation, intimate and clinical in alternating measure. Black Forest drifts intuitively from memory to fantasy to supposition, sifting through the deaths of loved ones and acquaintances and people in anecdotes and people on Six Feet Under in a way that’s at once cold and sparkling with life. I’m not calling it a memory palace of deaths, but I’m not not.

I reread Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station early this year—still find it extraordinary, still not wild about how much Adam Gordon reminds me of me—and inhaled a friend’s galley of The Topeka School over a summer weekend. It excites me to watch Lerner at work, processing the present at a rhythm that feels authentically like thought, and even as he widens his scope to include more zeitgeist, more history, more dimensions in his characters and their relationships, I’m spellbound by his knack for the fundamentally introspective work of airing their reasonings and neuroses and inner negotiations, which seem rational and sympathetic until you realize—eventually for me, I assume very quickly for lots of people—that maybe their shit’s been part of the problem all along. I would have called Lerner unmatched in his ability to pull this off compassionately before I read Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble (also over a weekend, also a friend’s advance copy): a plottier, smaller-scoped novel that nonetheless ends up being an even-handed, piercingly wise referendum on love and marriage and sex and gender. Both books experiment gently with shifting perspective, Topeka deliberately and Fleishman more sinuously, and both feel like classically ambitious attempts to get at the crux of a knotty modern predicament, in this case the meaning and function of masculinity. I’ll be revisiting both, slower, down the line.

I reread Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station early this year—still find it extraordinary, still not wild about how much Adam Gordon reminds me of me—and inhaled a friend’s galley of The Topeka School over a summer weekend. It excites me to watch Lerner at work, processing the present at a rhythm that feels authentically like thought, and even as he widens his scope to include more zeitgeist, more history, more dimensions in his characters and their relationships, I’m spellbound by his knack for the fundamentally introspective work of airing their reasonings and neuroses and inner negotiations, which seem rational and sympathetic until you realize—eventually for me, I assume very quickly for lots of people—that maybe their shit’s been part of the problem all along. I would have called Lerner unmatched in his ability to pull this off compassionately before I read Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble (also over a weekend, also a friend’s advance copy): a plottier, smaller-scoped novel that nonetheless ends up being an even-handed, piercingly wise referendum on love and marriage and sex and gender. Both books experiment gently with shifting perspective, Topeka deliberately and Fleishman more sinuously, and both feel like classically ambitious attempts to get at the crux of a knotty modern predicament, in this case the meaning and function of masculinity. I’ll be revisiting both, slower, down the line.

After not reading it for several years mostly because I thought the title was boring, I read Marie Chaix’s 1974 memoir-novel Les Lauriers du lac de Constance, then promptly reread it in Harry Mathews’s translation, The Laurels of Lake Constance, just to keep the spell going. Chaix makes Lerner’s and Brodesser-Akner’s perspective jumps look elementary, darting between voices and tenses sometimes from one sentence to the next, not out of formal showiness but to grapple with the multitouch impact of World War 2, and her father’s collaborationist career, on her family. (She herself was born in 1942, and comes into the story as a narrator maybe a third of the way in.) I no longer remember which prepared me for which—as I said, it’s a hasty ledger—but I recognized the same sly chameleonic interiority in Morgan Parker’s second poetry collection, Magical Negro, which tracks a sleepless mind’s path through a world of “Dylann Roof, Burger King, Urban Outfitters.” Parker’s is the cooler, nimbler voice—she sows devastating punchlines like landmines throughout her poems, while Chaix’s prose holds you pitilessly in the moment—but both model, unflinchingly, what it’s like to experience history as a simultaneously abstract and personal affliction. Parker: “And nothing rises up. And horror is a verb.”

I love environmental disaster movies and have an above-average tolerance for immersive theatre experiences, so reading David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth in Paris during a record heatwave—“so intense that a weather map of France looks like a screaming heat skull of death,” according to a Business Insider headline—a headline!—felt about right. His work in synthesizing a massive body of scientific research is admirable; his willingness to lean into its monumentally terrifying conclusions, to use fear and alarm in a way scientists can’t or won’t, is crucial. Some time around then I also read Erik Nielson and Andrea L. Dennis’s Rap on Trial, which expands on the excellent work the authors have been doing separately for over a decade cataloguing and decrying the harrowing trend of rap lyrics being admitted as evidence in U.S. criminal cases. May both shake something loose, though I realize our failing to address the first issue will eventually render the second moot.

Everything about Jen Bervin’s Silk Poems, a diaphanous little volume whose content is most expediently described as “silkworm giving a TED talk,” is strange and lapidary, right down to the obscurely troubling six-word description of how it was initially created: “written nanoscale on clear silk film.” There’s precedent for this kind of exploit—see for instance Christian Bök’s xenotext experiment, which encodes a short poem “into the genome of an unkillable bacterium”—but Bervin, whose previous works include erasures of Shakespeare’s sonnets (Nets) and a sumptuous facsimile edition of Emily Dickinson’s envelope drafts (The Gorgeous Nothings), is concerned more with materiality than with spectacle. As the difference in titular textures suggests, Ariana Reines’s A Sand Book is mostly what Silk Poems is not: gritty, folksy, squalid and chatty, sexy and gross, aimed with care and craftsmanship at something earthlier and more astral at once. I came away from both feeling better in tune with the intangible, by way of the utterly tactile.

Everything about Jen Bervin’s Silk Poems, a diaphanous little volume whose content is most expediently described as “silkworm giving a TED talk,” is strange and lapidary, right down to the obscurely troubling six-word description of how it was initially created: “written nanoscale on clear silk film.” There’s precedent for this kind of exploit—see for instance Christian Bök’s xenotext experiment, which encodes a short poem “into the genome of an unkillable bacterium”—but Bervin, whose previous works include erasures of Shakespeare’s sonnets (Nets) and a sumptuous facsimile edition of Emily Dickinson’s envelope drafts (The Gorgeous Nothings), is concerned more with materiality than with spectacle. As the difference in titular textures suggests, Ariana Reines’s A Sand Book is mostly what Silk Poems is not: gritty, folksy, squalid and chatty, sexy and gross, aimed with care and craftsmanship at something earthlier and more astral at once. I came away from both feeling better in tune with the intangible, by way of the utterly tactile.

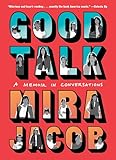

What else? I was grateful for Damon Young’s essay collection What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker and Mira Jacob’s graphic memoir Good Talk, both supremely lucid, good-natured but unsparing inquiries into how race, which is to say racism, gets inside your head to make you question how successfully, how convincingly, you’re inhabiting a pigeonhole you didn’t opt into in the first place. I was enchanted by Max Porter’s Lanny and Kevin Barry’s Night Boat to Tangier, both of which wrap inventive thickets of idiom and fragment around affecting tales of parenthood and loss.

I took a difficult journey with Jeannie Vanasco as she navigates the deceptively prosaic semantic aftermath of sexual assault in Things We Didn’t Talk about When I Was a Girl, and another one with Irma Pelatan, in L’Odeur de chlore, as she maps her body cathexis against a childhood spent swimming in a municipal pool designed according to Le Corbusier’s Modulor scale. Janelle Shane’s futuristic op-ed about feral scooters is hands down the 1300-word sci-fi novel of the year, and—since I’m not about to abandon the pairs conceit this close to the end—the last great thing I read as of this writing was Émilie Faure’s interview, in the biennial high-art review Mémoire Universelle, with world jigsaw-puzzle champion Sophie de Goncourt. She’s a magistrate by day who can put together a 500-piece puzzle in 40 minutes, a pastime which requires, she says with an irresistible lack of guile, “neither agility nor precision. A piece fits, or it doesn’t.”

More from A Year in Reading 2019

Do you love Year in Reading and the amazing books and arts content that The Millions produces year round? We are asking readers for support to ensure that The Millions can stay vibrant for years to come. Please click here to learn about several simple ways you can support The Millions now.

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The post A Year in Reading: Daniel Levin Becker appeared first on The Millions.