I read In Cold Blood for the first time earlier this year – and even then, it was under duress because it was a requirement for university. It’s not that I didn’t want to – in fact, the book had sat on my bookshelf for some years, just because it wasn’t a priority. Reader, let me tell you, I regret my delay. In Cold Blood is seminal, and obviously many before me have said so. It led me down the whirlpool of reading about Capote, fascinated by his own obsession with Perry Smith and the small town of Holcomb, Kansas.

With In Cold Blood, Capote set out to redefine writing. He sought to complete a nonfiction novel and wished to see awards lining his surrounds. The awards didn’t come, but in the long term Capote’s book is renowned as an American classic. In the background, Capote struggled with the executions of the murderers Perry and Smith, and found himself unable to complete another novel. Try as he might to finish Answered Prayers, Capote never managed it before his death, once commenting of it that “either I’m going to kill it or it’s going to kill me.”

The manuscript he worked on so persistently for many long years focused on the sordid tales of social classes, with characters that strikingly resembled the people Capote had known and socialised with over many years. Off the back of my newfound fascination with Capote, I read Swan Song, Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott’s first novel, which fictionalises the lives and tales Capote sought to use for his novel. Greenberg-Jephcott also provides background about Capote’s personal life, his childhood and his conflicting relationships with his family and friends. She paints a picture of a man who erred and failed to see it coming, and of women who turned their backs on him once he took advantage of them. The book is loaded with the egotistical, surface level lives of the elite and therefore is gossipy in tone – but that aids the reader to understand the world these people lived in, and the defining moments of their lives.

Capote was known for schmoozing with the top brass of his day – Babe Paley, Jackie Kennedy and her sister Lee, and Gloria Guinness and Marella Agnelli among them. Greenberg-Jephcott’s book seeks to tell the tales of these women as their confidante spears them in public, releasing sections of Answered Prayers to magazines, shocked when they sever ties with him and he experiences social suicide.

Though Capote remains an American icon, committed to film and reproduced times over, the stories of the women he took advantage of are less well known in the 21st century, their starlight lost to the passing of time in a way the creator of the Black and White Ball could never be.

The stories in Answered Prayers (and indeed more widely in that era) are almost entirely stories of white people. Capote wrote while civil rights were pushing to an ebb in the United States but his social circle, politically inclined as it was, remained the white upper crust. The women whose confidences he carefully cultivated were all of the same stock – but many of them told their own stories in book form in the years after Capote attempted it, and digging more deeply into their writing gives a reality to their voices Capote took away. Though we as readers cannot improve the history of publishing and authorship, we can platform voices that have been lost or forgotten, and we can persistently push for more diversity in our current reading, leaving behind an era of bookshelf exclusivity.

The stories in Answered Prayers (and indeed more widely in that era) are almost entirely stories of white people. Capote wrote while civil rights were pushing to an ebb in the United States but his social circle, politically inclined as it was, remained the white upper crust. The women whose confidences he carefully cultivated were all of the same stock – but many of them told their own stories in book form in the years after Capote attempted it, and digging more deeply into their writing gives a reality to their voices Capote took away. Though we as readers cannot improve the history of publishing and authorship, we can platform voices that have been lost or forgotten, and we can persistently push for more diversity in our current reading, leaving behind an era of bookshelf exclusivity.

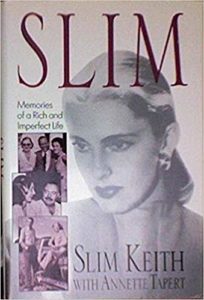

Of Truman’s so-called ‘swans’, not all wrote about their experiences – but some did. Among them was Slim Keith, who banished Capote from her life and never spoke to him again after his betrayal of her confidences. Slim: Memories of a Rich and Imperfect Life was published in the early 1990s and depicts her rise from nothing to the elite. Keith was undeniably interesting and undeniably imperfect – her name dropping and sense of ego pervade the pages of her book and I got the sense that she was never truly happy – but reading her own words instead of Capote’s was worthwhile. I also note that finding some of these older books is tricky – they’re not too widely available and neither have they been updated.

Of Truman’s so-called ‘swans’, not all wrote about their experiences – but some did. Among them was Slim Keith, who banished Capote from her life and never spoke to him again after his betrayal of her confidences. Slim: Memories of a Rich and Imperfect Life was published in the early 1990s and depicts her rise from nothing to the elite. Keith was undeniably interesting and undeniably imperfect – her name dropping and sense of ego pervade the pages of her book and I got the sense that she was never truly happy – but reading her own words instead of Capote’s was worthwhile. I also note that finding some of these older books is tricky – they’re not too widely available and neither have they been updated.

Though C.Z. Guest never wrote about her social life as part of the jet set, she did write First Garden, a book about her adoration of plants and gardening. Capote wrote the introduction to the book, which is full of charm and beautiful illustrations, but doesn’t shine much light on Guest herself.

The same can be said of Lee, a somewhat guarded photographic autobiography by Lee Radziwill, loaded with images of her family and friends, notes scattered throughout to help the coffee table book lover into the annals of the Kennedys and Bouviers. Radziwill also wrote Happy Times, which I haven’t managed to get my hands on yet. A friend has told me that it seems Radziwill was determined to leave behind bad memories in favour of recalling the beautiful moments she lived through – whether that’s an accurate assessment or not might be for another Rioter to say.

Last we come to Marella Agnelli, an Italian-born noblewoman who passed away earlier in 2019 in Turin. Agnelli was renowned for her elegance and opulence, and was known to Capote as The Last Swan, the youngest of the coterie of women he socialised with. In her book The Last Swan, Agnelli wrote that she tried to discourage Capote from his work on Answered Prayers, explaining that she had confided in him often but noting that he waited ‘like a falcon’. Her book is part autobiography, part photo essay, resplendent with images of her fashion, interior and stylistic life.

Of course, if you want to read Capote’s spin on these women’s lives, you can pick up a copy of Truman’s Answered Prayers, which was published after his death in the late 1980s. I haven’t read it yet; the voices of the Swans are the only ones I want to know, for now.

Source : A Study of Capote and His Swans