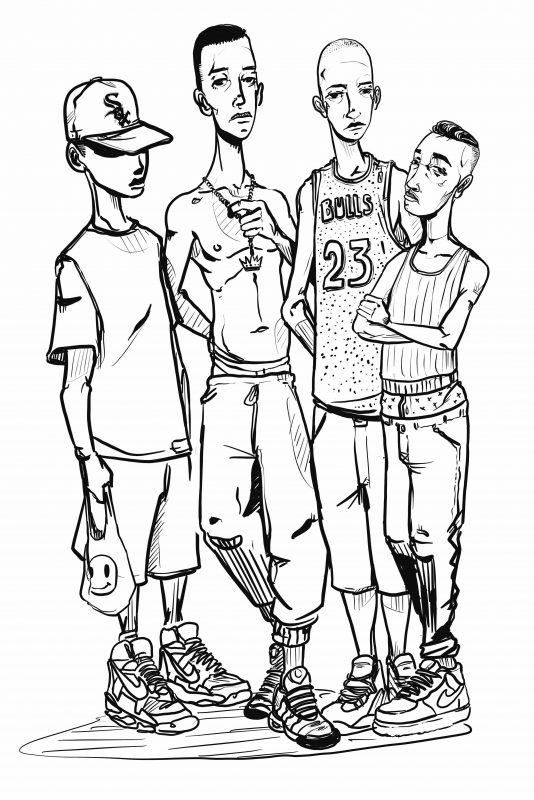

The language of poet Kevin Coval is melded with illustrations by Langston Allston in his eighth book Everything Must Go: The Life and Death of An American Neighborhood.

As his second collaboration with artist Allston (following 2018’s Milwaukee Avenue), the illustrated collection of poems serves as a tribute to Coval’s beloved home of Wicker Park in Chicago during the 90’s, but also chronicles the neighborhood’s growing gentrification that is displacing the community that Coval once knew.

Everything Must Go isn’t just a reclamation of Chicago, but a documentation of societal reinvention that stretches globally. Coval’s memory captures his environment with great detail, through rich sketches of nostalgic characters and a hope that the neighborhood’s essence isn’t entirely lost. I spoke with Kevin Coval about the basis and intention of Everything Must Go, the book’s timeliness in 2019 and how Wicker Park molded his artistic path.

Jaelani Turner-Williams: For Everything Must Go, you collaborated with New Orleans-based artist, Langston Allston. Since his hometown is states away from Illinois, how did you impart details for each drawing? Were these based on memory or abstraction?

Kevin Coval: It was a little of both. Langston and I spent time [in Wicker Park] walking around and seeing some of the spots that I mentioned. Also [Langston was] researching the book and going down my own memories, I ended up sharing with him some old photographs and some old videos at that time. I think Langston also brought his really unique perspective to the book and although it’s about Chicago, he was also thinking about rapid gentrification in New Orleans, particularly post-Katrina and what he’s seen on a regular basis. He was very much sympathizing [with] his own experience through my own, which is very powerful.

JTW: Did you know Langston previously?

KC: We met a few years ago when he did a show in Chicago in an abandoned storefront gallery space and I was immediately struck by what I think is a shared aesthetic, which I think about as a realist working-class portraiture. Langston was reflecting on a changing neighborhood in Chicago, Humboldt Park, and I was just working on the book at that time. I knew I wanted to tap an illustrator to work with me, because I was inspired by and influenced by the graphic novel and wanted to do something similar. The minute I saw Langston’s work, I thought, “this is that guy.”

JTW: What were the beginning stages of the book, or was gentrification a topic that you wanted to expand on for a while? What made 2019 the best time to release Everything Must Go?

For a working person, a person of color, the increased police presence makes the block a lot more dangerous than having to navigate street organizations.

KC: I’ve been reflecting on gentrification since I first came to be aware of the term, and also when I was living in Wicker Park in the 90’s, I saw it change pretty aggressively around me. I knew at some point I wanted to look back on that time because it was a special time for me, but it was also very odd time for the city and for that neighborhood. As I’ve been traveling because of the work, I get to see cities across the country [and] across the world who are going through pretty similar things. It wasn’t lost on me that you know that although I was writing about Wicker Park in the 90’s in Chicago, I’m also reflecting on systemic issues that are hurting working communities [and] communities of color on a daily basis.

When I was in Detroit, I wanted to write this book. When I was in certain sections of Miami, in Oakland, parts of Memphis, Nashville, Louisville, I started to think about this book as addressing socioeconomic, post-industrial global phenomenon that is not unique to Chicago, but I wanted to tell the story through that specific lens. It’s about the erasure of working people, gentrification is indeed about that process, and it’s nothing new to this moment, either. We’ve been doing that in this country since colonizers came and pushed away and created genocide for Indigenous people here. There is something about the maintenance of this process, I think particularly with an American white cultural amnesia where we don’t want to remember the past because it is painful for us to look at and so that’s part of the reason why we repeated that most.

JTW: You weren’t afraid to touch on having white privilege on “White on the Block.” Do you at times feel like you were idle to the gentrification in your neighborhood? What have been your methods of protesting against these changes?

KC: Gentrification is a complex issue and it’s not just about one person. Upon reflection, I realized that not only myself but the community of artists that I was a part of that time were essentially in a much larger strategy to help transform the city. Ways to resist the erasure of working people, ways to resist the escalation of costs that it takes to remain in the city is to really invest in the local communities, both in terms of the schools and also the local businesses. We need those things as viable factors to remain vibrant and to service our needs in the city. We need access to affordable wages and jobs, and those jobs that kept people in the neighborhood left. So many jobs fled the city and it begs the question, what kind of future are we imagining in this city when all the people are pushed away?

JTW: Some may deem gentrification as being improved from what the neighborhood was before. Do you find this to be a misconception?

KC: Recently, I was talking with a graffiti writer from Chicago who has been pushed out of the neighborhood that he was born in, and he was talking about how actually in the day, the neighborhood was a lot safer than it is now. For him, a working person [and] a person of color, the increased police presence makes the block a lot more dangerous than having to navigate street organizations. There were so many moments on his block back in the day that it would just be, you know, communities coming together for a block party and now you need to register and go through all this bureaucratic tape. To me, what makes the block safe or what improves the community is when you have people accounting for you, when you know the names of your neighbors, [when] they are looking out for you, your family and your overall community. When we disperse that community, that’s when the neighborhood begins to dwindle.

JTW: A focal part of Everything Must Go isn’t just the neighborhood, but the characters that called Wicker Park home. One of these characters was Sharkula in “Thigamahjiggee”, who was homeless, more or less. Why was it important to focus on a homeless character, when they’re often disregarded in their community. Do they uphold the community to some degree?

If we get rid of artists, if we get rid of the workers, what kind of city are we gonna have?

KC: For me, some of the folks who were experiencing housing instability were my first community members. They were the ones who I would see every day when I would be walking the block, and they were some of the first people in the community to know my name, and remember my name. So when I see someone on the streets like Sharkula or like Oba Maja [from “Oba”], who I mentioned as the poet laureate of Wicker Park, these were the folks who first accounted for me. I would see them and I would feel like I’m starting to have a place here. All [the] folks who I wrote about in the book began to give me a sense of home in place in that community.

JTW: You even shared your temporary displacement in “The Time I was Homeless”. What was the cause of this turning point and how were you able to return to Wicker Park? Can you pinpoint anyone in the community that was an aid to you?

KC: It was at a time when rent began to be increasingly and probably illegally raised too great of a percentage and I just wasn’t able to afford where we were living. I thought I had a place, then I didn’t have a place and I was in-between jobs, so I just ended up like a lot of working people when you’re living check-to-check. You are in that moment when you can’t rely on that particular type of income or that income is all over the place and you end up in a housing crisis situation where you don’t have a spot. Thankfully, I had people who all also looked out for me, I definitely lived in my car for a while but I had homies and different folks who would give me a couch for a little bit here and there and that made a lot of difference in the course of that year and change.

JTW: Are there any safe spaces remaining for those who’ve resided in Wicker Park before recent gentrification?

What makes cities special is the local flair and flavor, but if [we] begin to whitewash them, it all looks the same.

KC: Part of the reason why I wanted to write the book is because I’m one of the only people who I knew from the day who still even work in the neighborhood, and it’s because the youth arts organization that I’m the artistic director at, Young Chicago Authors, is still in Wicker Park. Part of it is that we just have a really good landlord who is [part] of the people’s law office and these are lawyers who will [make] sure the police force [is accountable] for egregious behavior and police brutality. They take care of us because they see us as a tenant and the work that we do is an important part of the neighborhood. So, they want us to stay there as they’ve stayed there. YCA is one of those spaces, but here and there you’ll definitely see a music venue that still has the longest-running open mic maybe in the country every Tuesday night at Subterranean, called 606 [Open Mic Hip Hop].

There’s street artists and folks in the neighborhood who remind me of [pre-gentrified] Wicker, but we can’t go back in time, either. This book is me going down memory lane, but it’s trying to raise a larger question about what is the future of cities and what is the future of the neighborhoods that makes those cities vibrant, but if we get rid of artists, if we get rid of the workers, what kind of city are we gonna have?

JTW: I noticed that in a few of your poems, you touch on memories of being in a setting and end with it transforming into another business. For example, “Ode to the Old Barbers”, when the barbershop became a massage spa. Is there a certain loss of culture when these spaces are forced out?

KC: One of the things I fear about gentrification is the homogenization of urban life and urban space, because for me if homogeny leads to imagined purity [and] cleanliness, it’s facism, really. For me, I love the details, I love the specificity, the particularity of a place and something like the barbershop, you can’t recreate. It’s about who was there, both the barbers and the clientele. Any place has a local flair and flavor, that’s what makes these cities so special, but if [we] begin to whitewash them, if we have that corporatization of urban culture space, it all looks the same. Not only is that a grotesque aesthetic, but I think it has much more sinister implications about the kind of culture and life we’ll be living.

JTW: Even if there aren’t ways to reassemble Wicker Park to how it once was, how has the community attempted to revive its original spirit?

KC: Working people will make culture wherever they’re at and so I think that you know the spirit of Wicker Park is really about the spirit of working people. Working people have moved in and around the city and have created very localized communities continuously. There will be a forever process of people desiring to find one another in community to have those communities be contested and for that friction to exist between the 99 and the 1 percent. Until we begin to have greater solidarity amongst working people, those communities will continually be moved, but there’s a possibility of solidarity and resistance of that force.

The post A City Can’t Live Without Artists and the Working Class appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : A City Can’t Live Without Artists and the Working Class