At some point this year, Sony’s very weird “Spider-Man Shared Universe” will continue with their third Spider-Man-less Spider-Man movie, Morbius. I say “at some point” since the movie has been moved multiple times — at the time of this writing, it’s currently slated for April 1, but whether that date will hold is anyone’s guess. But someday we will get the dubious pleasure of seeing Jared Leto as the title character, Dr. Michael Morbius, a.k.a. MORBIUS, THE LIVING VAMPIRE!

Now, technically, Morbius is not a vampire. He just, you know, injected bat DNA into himself to cure a rare blood disease and gave himself an insatiable bloodlust, an aversion to light, pointy teeth and pale skin, the ability to pass on his condition to others by biting them, flight, super-strength, super-healing…but he didn’t die, so he’s not a vampire. Because if there’s one thing comics love to do, it’s split hairs.

However, actual factual vampire or not, Morbius is vampy enough that he would have been banned for a couple of decades in the name of protecting the children. In fact, he first appeared pretty much as soon as possible once the vampire prohibition was dropped. I find this aspect of comics history fascinating, so I decided to drape some garlic around my neck and do a quick dive into the history of vampires in western comics.

Let’s stake a look at the timeline, shall we?

1939

I’m not sure if “Batman Versus the Vampire,” a two-parter which stretched over Detective Comics #31 and #32, is the first comic book to feature a vampire, but it’s certainly up there — Batman himself had only been around for four months at this point. In the story, our hero — not an un-vampire-like character himself — rescues his girlfriend Julie Madison from “the Monk” and Dala, vampires who he eventually kills with silver bullets because early Batman is wild. At this point in comics history, this element of horror is neither wildly popular nor scandalous; it’s just sort of a thing Batman does that day.

1950

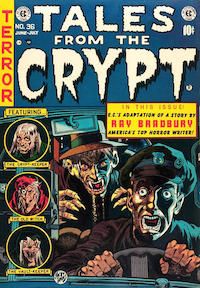

In the years after World War II, two of the most popular genres of comics were horror and crime, which grew increasingly lurid in their attempts to court their audience of returning GIs as well as kids. EC Comics was at the forefront of this trend, with books like Tales from the Crypt (and yes, the TV show decades later was inspired by this comic) and The Vault of Horror launching in 1950, both of which featured vamps a-plenty.

1954

As comics got darker, sexier, and more violent, parents became increasingly concerned with what their children were reading. This reached a fever pitch in April of 1954, when congressional hearings were held to discuss the danger comics posed to America’s youth. These hearings, uh…didn’t go well for the comics industry. They led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority later that year, the industry’s self-regulatory board, which approved comics before publication. You didn’t have to submit your comics for approval, but most retailers wouldn’t carry books that didn’t carry the CCA’s seal of approval on their cover, so you’d go out of business either way. Predictably, the Code banned sex and all but the mildest violence, disrespect for authority (it was the ’50s, after all), “sexual abnormalities” and “sex perversion” (read: queer content), and the like.

In a move that was perhaps less about protecting the children and more about forcing the ultra-popular EC Comics out of business, the Code also banned “all scenes of horror,” the use of “horror” or “terror” in a title, and anything that went bump in the night, including “the walking dead,” “werewolfism,” and…vampires.

1962

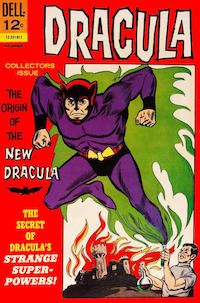

Dell Comics was one of the few holdouts that never submitted its comics to the CCA for approval, something they could get away with because they had a massive amount of market share and a wholesome reputation, thanks to publishing tons of family-friendly licensed properties like Disney’s bestselling Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge comics. And so in 1966 they were perfectly free to reimagine Dracula as a superhero, which is a weird idea that was hilariously goofy in execution.

1965

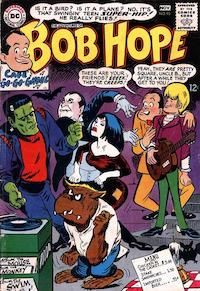

Everything in the Code was up to interpretation, of course. Sometimes this meant that even though the code said nothing about race, the CCA could overreach their authority in an attempt to be super racist. Sometimes this went in the other direction, and they permitted things that violated the letter of the law but not the spirit. The provisions against spooky things were aimed at eradicating the extremely dark horror that parents thought was harmful to children in the late ’40s and early ’50s, but comedy vampires could squeak through. Thus you got things like Bob Hope (yes, that Bob Hope) hanging out with all of the Universal movie monsters, Dracula included, in his own long-running comic book for several years in the second half of the 60s.

1969

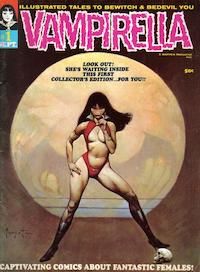

One of the weird little quirks of the Comics Code was that if you published what was obviously a comic but in the slightly larger dimensions of a magazine, you didn’t have to submit it to the CCA and newsstands would happily sell it without the seal. (Mad Magazine is the most famous example of this workaround.) So it was with Warren Publishing’s black and white horror line, which led to the 1969 debut of one of the most famous vampires in comics, Vampirella.

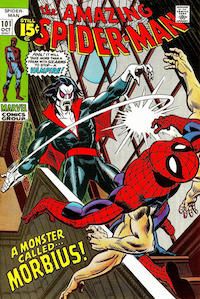

1971

In 1971, the CCA updated their prohibitions, since the strict rules of the mid-50s seemed dated and ridiculous in light of, you know, the entire decade of the ’60s. Serious vampires were now permitted, if treated “in the classic tradition,” i.e. Bram Stoker-style. The change came in February; Morbius debuted later that year as a tragic and sympathetic Spider-Man villain who would quickly become a protagonist in his own right. The bloodfloodgates were open!

1972

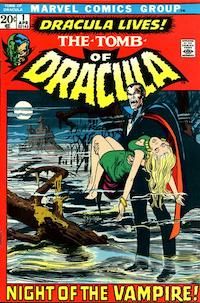

Marvel went all in on vampires once they got away with Morbius, though they adhered pretty strictly to the “in the classic tradition” rule with their next vampiric offering, The Tomb of Dracula. Ol’ Alucard has remained a villain lurking around the Marvel universe ever since, fighting everyone from the X-Men to Howard the Duck.

1973

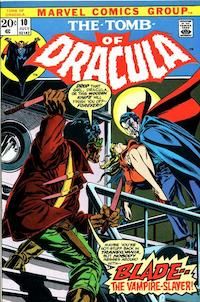

Marvel launched five black and white horror magazines in 1973, including Dracula Lives! and Vampire Tales. More importantly, The Tomb of Dracula #10 introduced their most important vampire-related character: Blade. A combination of the growing horror trend and the then-popular Blaxploitation trend, Blade came into greater prominence as a lead character in the vampire-loving ’90s, and was even one of the first Marvel characters to hit the big screen, with 1998’s Blade.

1981

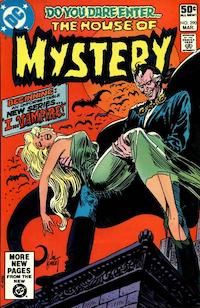

I certainly don’t want to imply that DC had no vampires until 1981 — all those Bob Hope comics were published by DC, after all — but horror in general was traditionally a much smaller part of their oeuvre. However, 1981 marked the introduction of a major heroic vampire character, Andrew Bennett, in a backup feature called “I…Vampire” in the comic The House of Mystery, where it quickly became the lead feature. Bennett has stuck around as part of the occult side of the DC universe ever since.

Hm, this cover sure does look exactly like The Tomb of Dracula #1, doesn’t it…?

1991

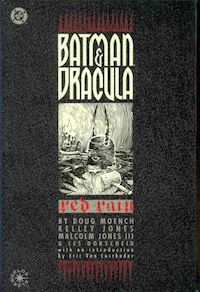

Vampires were popular in the ’90s, and we saw a number of bloodsucking developments in comics in this decade. One of the most notable was Batman & Dracula: Red Rain, which became one of the most popular installments of DC’s Elseworlds line (a.k.a. alternate universe stories), eventually growing into a trilogy.

2007

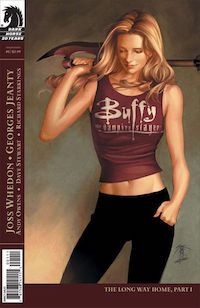

By the 21st century, the CCA was functionally dead (DC and Archie, the last major publishers to even nominally adhere to it, finally stopped the charade in 2011), and so there are plenty of vampire comics to be found in the Aughties. I chose to highlight 2007 for two vampire slaying heroines: Buffy the Vampire Slayer had had tie-in comics since 1998, but Season Eight, the canon continuation of the show published by Dark Horse, began this year, and Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter finally made it to comics in a series of graphic novels by Dabel Brothers Productions and Marvel.

2010

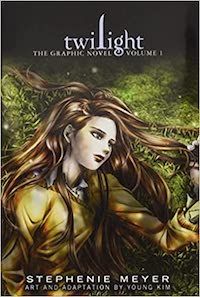

Well and truly proving that the idea of comics with vampires being Dangerous To The Youth had been staked through the heart, Twilight: The Graphic Novel was published in 2010. (I mean, I don’t know that Twilight is great for kids, what with all the romanticizing of stalking, etc. But it never caused a moral panic.) Over at Marvel, beloved X-Men mainstay Jubilee became a vampire, because why not?

2018

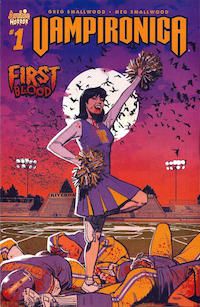

Okay, actually, here’s the proof: Archie Comics, once one of the staunchest proponents of the Comics Code and its longest holdout, began publishing the darkly humorous Vampironica, which is part of their critically acclaimed horror line and is…basically exactly what you think it is.

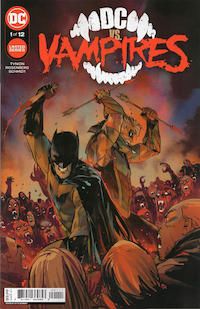

2021

In late 2021, DC began publishing DC vs. Vampires, a miniseries noteworthy mostly because of how completely unnoteworthy it is to publish a series in which DC’s beloved heroes are all killed by or become vampires. But history has not been forgotten: in issue #2, Batman references his past confrontation with the Mad Monk and Dala, way back in 1939. Some things, especially vampires, don’t stay buried.

The idea of a ban on vampire comics comes across as silly these days, as do so many other things about the Comics Code. Some of the comics I’ve mentioned above are wonderful, some are awful, and a lot are frankly forgettable. (Sorry, Bob Hope.) But whether you’re a vamp enthusiast or not, with so many schools and libraries facing increasing book challenges, it’s important to remember that censorship always sweeps up the good, the marginalized, and the harmlessly ridiculous along with the so-called “dangerous.”

In conclusion: see Morbius if you feel like braving the theaters (and Jared Leto), rewatch Blade if you don’t, stick up for the First Amendment, and remember that vampires can’t come in unless you invite them.