Photography is not yet 200 years old, and yet humans have been interacting intimately with plants since before we were actually H. sapiens. Most primates are omnivores who lean heavily toward the “vegetarian” side of the scale, and we are no exception. Throughout our development, humans have learned to identify plants in myriad ways, especially the ones that are edible or have healing properties, and especially when we move from one climate to another. Before we were able to take detailed color photographs of plants, we were drawing them as clearly and identifiably as possible to pass information along to our neighbors and our children.

Because the ultimate goal of botanical illustration is not necessarily to be attractive, but to literally illustrate a plant for identification, there is a distinction between botanical illustration and botanical painting. Botanical illustration almost always includes many life stages of a plant and its various bits and pieces. Because many plants look alike, the combination of life stages and individual parts is necessary to distinguish similar species from one another.

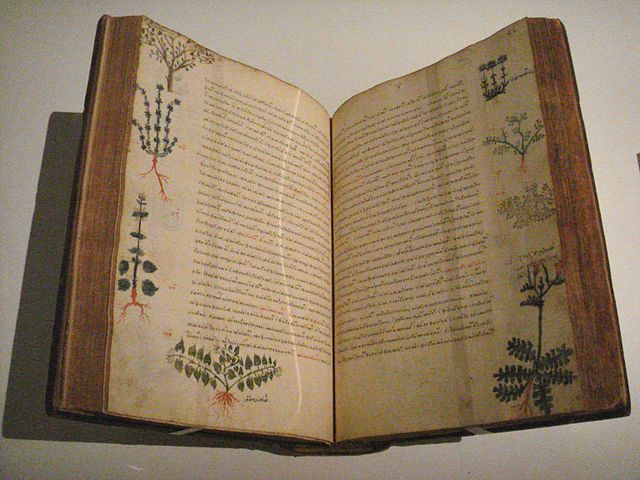

Somewhere between 50 and 70 CE, the Greek botanist Pedanius Dioscorides wrote a five volume pharmacopoeia while traveling with the Roman army. His work contained detailed illustrations of over 600 plants and the over 1000 medicines that could be created from them. Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica became the bedrock text for plant identification and was copied thousands of times and in wide circulation from his original publication until today. Old and even ancient copies can be found around the world, often with additions about local plants and remedies.

During the European Medieval period, art in general took a less life-like approach, and the identification of plants by illustration was largely relegated to illuminated copies of De Materia Medica. The Renaissance brought the reemergence of perspective in drawing and also put forward new thinking about botany and pharmacology, although both disciplines still relied heavily on Pliny the Elder’s Natural History and Dioscorides.

Then the Age of Exploration began, and from the early 1600s through the mid 1800s, Europeans were dashing about the world in wooden ships, wreaking havoc among indigenous populations of flora and fauna alike. Any expedition worth its literal salt had a naturalist on board to carefully catalog and preserve newly encountered plants and animals. The naturalist would take copious notes and create a herbarium, which is a collection of plants pressed into books. These herbariums would be brought back to the expedition’s home country, where botanical illustrators would carefully measure and dissect the plants to create a meticulous illustration, usually in watercolor, for reproduction and dissemination.

Occasionally an expedition would take both a naturalist and an artist, such as the famous expedition of the HMS Beagle (1832–1835). This arrangement allowed the artist to work from life and to create images of plant life in its natural habitat. By the voyage of the Beagle, botanical illustration was a respected profession, bridging the divide between the science of botany and the art of painting.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Going back to the Golden Age of Exploration (at least from the perspective of the explorers), the cataloguing of newly encountered plants was critical for several reasons. The first and most important was to bring new foods and spices back to Europe, hopefully to impress your monarch’s bored and finicky palette; this is how Europeans were introduced to all foods native to the Americas, including the potato, the tomato, maize, and squash. (Side note: prior to the introduction of maize to England in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the word “corn” meant simply any generic grain, deriving from the Proto-Germanic word korn, meaning “a single seed.”)

Another reason for such a catalogue was to find new medicines, new pigments for dyes and paints, and — of course — new recreational drugs. Humans are, after all, curious creatures and we like to experiment with the limits of things. Botanical illustration provides a way to catalogue Kingdoms Plantae and Fungi in a way that cannot be conveyed in words alone. Many botanical illustrators will argue that the same holds true today even with the advent of photography because while a photograph captures a moment in the plant’s life cycle, a single botanical plate can show all the life stages of a plant in one image:

Botanical illustrators are still being asked to help catalogue and preserve various plant species, both old and new, all the time. Herbariums are being expanded yearly; according to a report by Kew Gardens in the United Kingdom, there are around 391,000 recognized types of vascular plants on Earth, a classification which doesn’t include most algae or any fungi — of which there are an estimated 2–4 million species, only around 148,000 of which have been described. In 2019, 90 types of begonias alone were identified and added to that number, along with five new types of onion. In 2013, Drosera magnifica was identified as a new plant when a researcher from the University of Sao Paulo came across a photo of one on Facebook and realized it had never yet been recognized.

Currently in my own area, the Northern California Society of Botanical Artists (of which I am a member, full disclosure) is putting together a florilegium of the plants that grow on Mount Tamalpais as well as one with the much broader subject of “the beauty of leaves.” All this to say, botanical illustration has perhaps yet to hit its heyday, despite the amazing work that came out of the 17–19th centuries. The next time you come across a botanical illustration, take a moment to appreciate the incredible work and history behind the piece itself.

Fore more flower power, check out these pressed-flower bookmarks. Feeling some fictional floral reads? Check out these fiction books about flowers for those spring vibes all year long.