Fairytales, myths, folklore, urban legends, all of those compact, strange stories that we pass from person to person and between generations—they’re the first stories we encounter, a medium for transmitting ideas and expectations, a window into our individual and our collective imaginations. All of this, and they still have to be entertaining enough to hold our interest.

The stories we choose to tell—and how we choose to tell them—speak to what we value. For this reason, I also love retellings of folklore, which are always in conversation with their source material. Sometimes that conversation is about the original story itself, the world that produced it, or how our own world has changed since. My favorite retellings, though, are those that use the opportunity to reflect on the nature of storytelling— its capabilities, its limitations, and its place in defining who we are.

The strange power of storytelling is central to my short story collection, Fruiting Bodies. The collection’s eight stories all examine different aspects of the power narrative holds over our lives, and a number pull directly from fairytales. Both folklore and other authors’ recreations of it played a major role in shaping my understanding of what a story can do, and so, below, I want to share with you eight of my favorite retellings that are also, on some level, stories about telling stories.

Lavinia by Ursula K Le Guin

A retelling of The Aeneid centering Aeneas’s eventual bride, Lavinia shines with the same deeply thoughtful imagination that has made Le Guin’s writing famous. The titular Lavinia hardly appears in the original Aeneid, except for the space of a few lines, and here Le Guin gives her both life and a voice to speak on her own writing. A grounded narrative of Lavinia’s life, from childhood through to after her marriage to Aeneas, occasionally breaks into surreal interludes where she speaks with Virgil, the poet who immortalized her, but, in Lavinia’s words, “Did not sing me enough life to die.” Lavinia is both a lovely and literary piece of historical fiction and a meditation on what it means for a person to become a story, or to be a side character in someone else’s.

Deathless by Catherynne M Valente

Deathless pulls characters and scenes from Slavic folklore into a power struggle set against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution and its aftermath. Koschei the Deathless, Tzar of Life, spirits young Marya Morevna away from wartime Leningrad to be his bride. In a fairytale world full of strange and lethal laws, Marya fights for agency in her marriage and her new kingdom, as the Country of Life continues an endless war against the Country of Death, and Russia goes to war with itself. Even the demons and legends of Deathless are moved by greater forces, by history and by the shape of their own stories. Valente’s prose is lush and brutal, achingly effective at submerging the reader in the world of Deathless, a strange and terrifying place that you will never want to leave.

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood

A particular gem in the treasure trove of Margaret Atwood’s work, The Penelopiad offers a feminist answer to The Odyssey. In a series of poems and monologues, Atwood gives voice not just to the titular Penelope, the famously patient bride of Odysseus, but to all of the Odyssey’s neglected women, from Helen of Troy to the maids hung for laying with Odysseus’s unwelcome guests. The characters, somewhat like Le Guin’s Lavinia, speak from both within their story and beyond it, reflecting on their human lives and their status as legendary figures. Penelope complains:

“What did I amount to, once the official version gained ground? An edifying legend. A stick used to beat other women with. Why couldn’t they be as considerate, as trustworthy, as all-suffering as I had been?”

In the Penelopiad, Atwood specifically explores the roles women take in myth and legend, and allows her protagonists to be outraged on their own behalf.

The Einstein Intersection by Samuel R Delaney

Some of the most dreamlike and enchanting science fiction I’ve encountered, The Einstein Intersection takes place on a future Earth, abandoned by humans but still haunted by the ghosts of our stories. These ghosts are taken up by the planet’s new inhabitants, an alien species seeking to fit themselves into our vacated niche. Figures from myth and legend as well as contemporary pop culture dance through The Einstein Intersection, legends from Orpheus to the Beatles serving as raw material from which our planetary successors construct their own version of humanity, throwing into relief just how important those same narratives have been in constructing ours.

The Merry Spinster by Daniel M Lavery

Daniel Lavery’s The Merry Spinster turns popular stories delightfully sinister, with source material ranging from the bible to Frog and Toad are Friends. In each story Lavery leads readers into an increasingly bizarre and unsettling world, as with “The Daughter Cells,” a retelling of “The Little Mermaid” that leans into the full strangeness of deep sea creatures or “Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Mr. Toad,” in which a whimsical group of woodland animals torture their friend in ways they insist are for his benefit. (“I don’t believe we have ever Drowned Toad before,” Mole said. “I suppose Helping is a bit like Drowning.) Lavery’s stories play not just with the conceits of the source material but with their tropes and structure. Several stories unpick fairytale roles from who we might assume will play them—a princess, for example, might be a person of any gender, because a princess in a fairytale is not simply a person but a function, a role that must be filled. The Merry Spinster isn’t quite like anything you’ve read before, but when you’re done you’ll badly want to read more like it.

Witches Abroad by Terry Pratchett

Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books are a source of joy and comfort that I believe everyone should have in their lives. While Witches Abroad is not the first of the series, the books don’t have to be read in order and all stand up well on their own. Witches Abroad follows three witches from the remote town of Lancre. When their coven’s youngest member, Magrat Garlick, inherits a fairy godmothership she doesn’t know what to do with, she and her senior witches—Nanny Ogg and Granny Weatherwax—are swept into a foreign land and a story already in motion. Pratchett parodies and pokes (loving) fun at popular fairytales in Witches Abroad, but, as with all of Pratchett’s humor, Witches Abroad’s meditation on tropes and narrative is as incisive and thoughtful as it is funny. Pratchett renders stories as a magical force unto themselves. As he puts it, “People think that stories are shaped by people. In fact, it’s the other way around.”

The Mere Wife by Maria Dahvana Headley

A Beowulf retelling set in modern American suburbia, The Mere Wife is as gorgeous as it is strange. Central to the novel are two mothers—Willa Herot, a wealthy but unhappy housewife living in her husband’s housing development, and Dana Mills, a traumatized former soldier living in a cave just outside. Dana’s son, Gren, was conceived under mysterious circumstances and, Dana is sure, will be perceived as a monster by anyone who finds them. As Gren grows older, though, he takes an interest in Willa’s son Dylan, and Dana’s attempts to protect him grow more desperate as their worlds drift closer together. At its core, The Mere Wife is a book about monsters, how we create and define them, how we treat them, and the stories we tell about them.

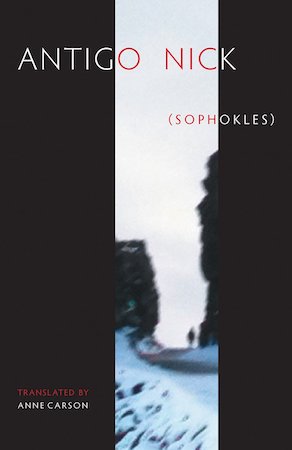

Antigonick by Anne Carson

Anne Carson is a classicist and translator as well as a poet and playwright, and Antigonick sits beautifully at the intersection of these strengths. The book is arguably more translation than retelling, though it isn’t trying to be a literal translation—characters make references to Brecht and Hegel, opine on their own stories. Carson achieves a different kind of translation, though. For me, Antigonick was a doorway to the entire genre of Greek tragedy, which is captured here at its starkest and strangest, loveliest and most brutal. It’s yet another type of translation, though, that Carson lays out as the explicit goal of the project, a question of what translation is or, at least, what is most vital to translate. Antigonick opens with an original poem by Carson, “the task of the translator of Antigone” which ends with these lines:

perhaps you know that Ingeborg Bachman poem

from the last years of her life that begins

“I lose my screams”

dear Antigone,

I take it as the task of the translator

to forbid that you should ever lose your screams

The post 8 Retellings of Fairytales, Myths, and Folklore appeared first on Electric Literature.