I’ve always been a prolific reader, but until the year I graduated from college, I hadn’t read a single book by an author of Indian origin who’d grown up, like me, in America. Year after year, I searched for authors from the Indian diaspora whose work had something to do with my own life, until eventually I realized several years ago that, for me, the descriptive term “Indian” feels flattening and false. “India” is a nation; it’s a national identity, not a culture, nor an aesthetic. There are too many distinctive cultures, languages, faiths, castes, customs, practices originating within the boundaries of India, all of which affect the materiality of people’s lives, the material of their storytelling.

So why a list of diaspora novels?

There’s long been a danger within the ethos of “multiculturalism” that one vision of a nation or diaspora will stand in for the whole. A reader from another country might read a single book by an author of the Indian diaspora and feel that’s enough, now I know, in spite of the cultural heterogeneity of the nation and the diaspora. This year is a banner year for inventive and stirring and memorable books by us, the diaspora. It might be the most exciting year so far for Indian diaspora books within my lifetime.

Books can feel like doors, permission, freedom. This list of the 8 books from the Indian diaspora that feel new and thrilling is a starting point, not the last word. There are more of our stories coming, I know.

The Good Girls by Sonia Faleiro

Sonia Faleiro’s The Good Girls is one of the best works of narrative nonfiction I’ve read. I’m pretty sure, by the end of the year, it will be one of this year’s best books, period. It’s the true crime story of two girls in an Uttar Pradesh village who are found hung from a mango tree. It’s also a feminist work about the girls’ death and the murder investigation that follows. The book unearths the way power works in an Indian village, and how that power is upheld and reproduced, not only by the legal system, but also by ordinary people who don’t believe they’re doing anything wrong. What sets it apart for me is that even though it’s highly particular and specific, it reflects a much larger story about how power works in insular communities to disadvantage and harm girls, especially poor ones that nobody shelters, everywhere around the world. This power can be as simple as rabid gossip. More importantly, perhaps, this power works through the emotion of shame, and that’s an insight of which everyone should be aware.

Gold Diggers by Sanjena Sathien

Sanjena Sathien’s debut novel Gold Diggers is magical realism about striving upper-middle-class Indian Americans. Told in first-person, the protagonist is a hapless teenager in Georgia with second-hand ambitions. He’s surrounded by academically achieving Indian Americans and other Asian Americans. He longs to be as talented as them, and one night, when he sees his beautiful neighbor—the object of his lust—drinking gold, he figures out how he might do it. There are scenes in this novel that so accurately reproduce the affluent Indian American experience of the aughts, I wondered if it was really intended as satire. Around halfway through, the novel breaks open. There’s a scene—and speech—that made me recognize just how brilliant this book is. The second half, in particular, is a dazzling gold heist story. Mindy Kaling is adapting this book, which makes perfect sense, but get in on the ground floor.

China Room by Sunjeev Sahota

Sunjeev Sahota’s China Room is the diaspora novel I most anticipated this year. His first book, the unsettling Ours Are the Streets, is about a young man of Pakistani origin who grew up never belonging in England and returns to Kashmir and Afghanistan where he is radicalized. His second book The Year of the Runaways is phenomenal, detailing caste and racial discrimination in India and Britain’s Sikh communities. The China Room is utterly different, but it did not disappoint. It’s a dual narrative of a young bride in rural Punjab prior to Independence who is trying to figure out which of three husbands is hers, as well as the story of her great-grandson. Her great-grandson comes back to his uncle’s house in Punjab from a racist small-town in England, in hopes of shaking his addiction. It’s intimate and startling.

Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri

Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts is a departure but retains her usual grace and close attention to moments. Told in brief chapters, Lahiri wrote the novel in Italian and then translated it into English. It’s a subtle, unadorned story in small movements, but less culturally-situated than her other fiction. A solitary narrator wanders around a European town and makes observations and thinks about her life. In another writer’s hands, this might be dull, but she somehow makes it a luminous consideration of estrangement. The narrator says at one point: “Solitude: it’s become my trade. As it requires a certain discipline, it’s a condition I try to perfect. And yet it plagues me, it weighs on me in spite of my knowing it so well.”

Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir by Akwaeke Emezi

Akwaeke Emezi’s work has genius in it. I’ve never seen anything like what they do to bind language to their identity as a Black trans person of mixed Indian Tamil and Nigerian Igbo descent. Their language also expresses an overlapping reality as an ogbanje, or spirit who looks like a human.

In Dear Senthuran, Emezi writes their memoir in letters. Each letter is addressed to a different person in their life, but together the letters form a narrative about growing up trans in Nigeria, transition through two surgeries, gender identity, relationship struggles, an MFA program, the experience of writing and publishing their innovative debut novel Freshwater, and the aftermath of that publication. As they put it, “What words do you chant into the space between spaces, to bend your desires into reality?” This is language that stuns, rather than aims for pretty construction, while also revealing so much of a brilliant inner life. It’s a must-read, perhaps especially for experimental writers or artists of color who are trying to figure out a place for themselves in the existing market.

Antiman by Rajiv Mohabir

Rajiv Mohabir’s Antiman is a hybrid memoir about coming of age as an Indo Guyanese queer poet. It’s striking in its play with genre, and vivid in its imagery and metaphor. Mohabir weaves together fragments of his grandmother’s Bhojpuri songs with his own poems and prose about growing up queer—first in Florida with his family, and then his later coming of age in Queens, New York City. His family, which has coolie, mixed-caste ancestry and a history of indenture in Guyana, converted to Christianity. Mohabir sees in his father’s resistance to Hinduism a kind of self-hatred; he attributes this to colonialism.

The memoir is an unusual, lyric glimpse into Mohabir’s perspective, as well as a window onto a world that is severely underrepresented in English letters. It’s artistically unique, although it shares a bit of background with Gaiutra Bahadur’s earlier Coolie Woman, which is a well-researched family history and narrative of indenture. In contrast, Mohabir takes a personal, confessional approach, fusing poetry and fragmented memoir together to tell the story of a sexual and political coming of age.

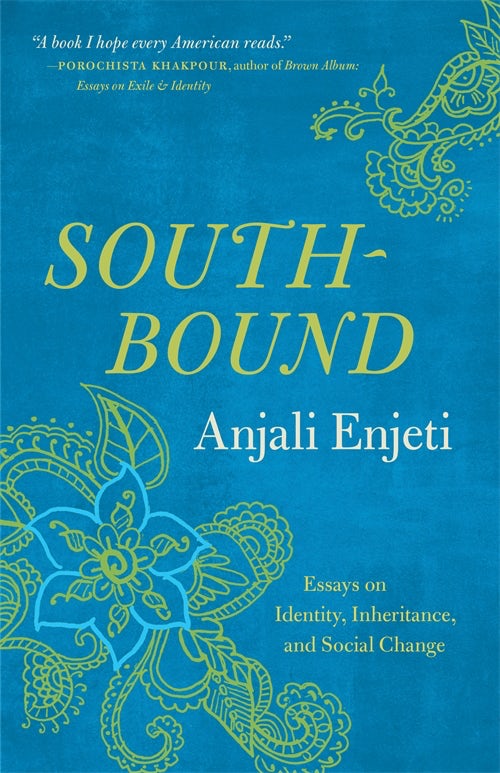

Southbound: Essays on Identity, Inheritance, and Social Change by Anjali Enjeti

Anjali Enjeti’s Southbound is a thoughtful essay collection about growing up multiracial and Indian American in America and her journey of activism. Like Sejal Shah’s collection This is One Way to Dance, it brings to light nuances of growing up in America as a person of Indian ancestry. It pays particular attention to hybrid or mixed-race identity—Enjeti is of Indian, Puerto Rican, and Austrian descent. She has a talent for illuminating personal transformation. Repeatedly, she writes about starting out with one view and then transforming her outlook based on lived experience and learning more. She writes essays about the complexity of experience and belief. For instance, she writes about the distinctions in feeling between her support for women who choose abortion before having children, and her view afterward. It’s important in these next several years to stay involved in activism and the political process, to build a better America, and to avoid a repeat of the last four years. Southbound is timely, speaking to this need.

Radiant Fugitive by Nawaaz Ahmed

I’ve never read a novel like Nawaaz Ahmed’s Radiant Fugitive, and, I kid you not, I’ve been waiting for this tremendous, complex, moving novel for years, but never expected to receive it. It’s the inventively-told story of three generations of a Tamil Muslim family in Chennai, San Francisco, and Texas. Two Tamil Muslim sisters take different approaches to their faith and lives before and during the Obama years. Seema is a lesbian Muslim activist in San Francisco who gets pregnant with a straight-edge Black lawyer she met at a protest. Her sister Tahera is orthodox, working and raising children in Texas, while struggling with Seema’s sexual orientation. Memorably, gorgeously, parts of the book are narrated by Seema’s baby in a direct address to his grandmother as he’s being born. I cried. There is so much of life in this book.

The post 8 New and Forthcoming Books by Writers from the Indian Diaspora appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : 8 New and Forthcoming Books by Writers from the Indian Diaspora