When I was a kid, I used to love going to friends’ houses to play, and I could be pretty shameless about finagling invitations. My friends had TVs and better snacks, yes, and some even had trampolines, but these were just fringe benefits. Mostly I loved going because I was fascinated by their families. I loved seeing how my friends and their parents interacted, whether they ate dinner separately or together, whether the mother reprimanded us for our misbehavior herself or phoned the father at work to really lay down the law. Half-Catholic, half-atheist, with a complicated custody situation with my alcoholic biological father, I was an outlier in my mostly Mormon elementary school, and I studied my friends’ families like an anthropologist. On Monday nights, especially, when I knew it was Family Home Evening at my best friend’s house, I’d call and casually inquire about maybe coming over. I relished sitting in the living room with her and her brother and parents, answering questions about Choosing the Right and the Pearl of Great Price, and watching how the parents and kids spoke to each other, looked at each other, how they expressed encouragement or displeasure or love.

Each of my characters in my debut novel, The Five Wounds, is profoundly aware of their dual roles as child and parent. After a fight with her mother, 15-year-old Angel shows up at her estranged father’s house enormously pregnant and looking for support. Amadeo, for his part, is stuck between childhood and adulthood, between his role as Angel’s father and as a son still dependent on his mother. When Angel’s baby is born, the whole family must reconsider what it means to care and to accept care. Separately and together, in their halting ways, they attempt to parent children they do not feel equipped to save.

Here are eight books about the power dynamics between parents and their children:

A Legacy by Sybille Bedford

I plucked Sybille Bedford’s semi-autobiographical novel from a giveaway box. I’d never heard of her, but I was instantly entranced by the tone, by her evocation of Europe before the Great War. The narrator, Francesca, is raised in part by the parents of her father’s first wife, members of the Berlin Jewish upper-middle-class, in their insular and heavily carpeted home. Her father’s family, by contrast, is located in the chilly countryside, Catholic, aristocratic and brutal. There is urgency in the way Francesca pieces together all the strands of family history, secondhand details and half-told stories—every detail from the past bears on the present and on Francesca’s understanding of herself. Writing about her long-dead uncle, she writes, “The memory of the boy who was a man and died before I was born, and of the school I never saw, were part of the secret reality of my own past.”

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

Brit Bennett’s excellent second novel follows the diverging paths of Desiree and Stella, twins who were once inseparable, but whose choices lead them to occupy completely separate worlds. The sisters are born in a town where Black inhabitants define themselves by the lightness of their skin. One sister marries a much darker man and, before she flees from her violent marriage, has a child. The other sister runs away with her white boss and marries him, passing as a prosperous white housewife. Both sisters have daughters, and the story plays out in parallel as we follow these mother/daughter pairs through the decades. The daughters’ lives are shaped by their mothers’ choices and hopes and shames, and they must confront their histories when, inevitably, their paths cross. Bennett’s insightful exploration of family, betrayal, love and race in the second half of the 20th century is moving, entertaining, and full of heart.

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang

The stories in Sour Heart are loosely connected, spiraling out from a single apartment in Washington Heights where five families, newly arrived from China, sleep in a single room on mattresses on the floor. These families, forced into such close quarters, absorb and resent each other’s stories, and, though the families go their separate ways and fulfill separate destinies, they become forever linked to each other. From the first propulsive paragraph, a breathless two-page account of a family’s perpetually clogged toilet and the ordeal of running in all weather to the Amoco station across the street, I was hooked. These stories overflow with joy and rage and yearning. I was moved by the depiction of intimacy between parents and children in these stories. Nowhere else have I seen such tender expressions of a child’s ardor for her parents, and the pain of the inevitable ripping asunder.

House of Broken Angels by Luis Alberto Urrea

Some characters take up residence in your heart. The House of Broken Angels is overflowing and joyful and expansive while also dealing with incredibly painful material, which is to say that it is about the experience of living in a family. The novel follows Big Angel and Little Angel, the oldest and youngest brothers in a family that sprawls across borders and languages and generations. Both Angels live in the shadow of their formidable father, Don Antonio, who shaped their lives with his gusto and abandonments. Big Angel has, his whole life, prepared himself to be a different kind of patriarch, loving and supporting his wife and children and vast, vibrant circle of relatives; by contrast, Little Angel, the much younger half-gringo half-brother, is alone, and approaches his past by studying it academically, as an outsider. Urrea captures how even in the same family, each child inhabits a different country.

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li

This perfect short novel is a conversation between a grieving mother and her teenage son Nikolai, who has committed suicide. The dialogue takes place in a kind of timeless liminal space between this world and the next, between the concrete world and the disembodied interior world of the imagination and the heart. The intimacy between mother and son reaches across these divides. As a reader, I am constantly aware that I am listening in on a conversation that is private and tender and of the utmost importance; yet, alongside the sense that I am intruding on this deeply personal grief, I feel absolute gratitude for the chance to get to know this boy who has been lost to the world. The premise is sad, of course, but the novel is shot through with joy and humor, and Nikolai’s wit and vivacity are unchanged by death. The teenager joshes his mother as teenagers do, gives his writer mother a hard time for using clichés, and they spar playfully with puns and metaphor. This novel is a heartbreaking gift.

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

Set in a Maine town, these linked stories center on Olive, a prickly retired teacher whose care and disapproval have shaped the generations of children that have passed through her classroom. This book is about many things—about marriage, about community, about grief, and about what we owe each other. But the element that moves me most is the depiction of Olive’s relationship with her son Christopher. She was hard on her sensitive boy, trying to toughen him to face a world that she fears will crush him, and she is bereft when, inevitably, he turns away from her, finding healing and acceptance clear on the other side of the country.

In my favorite story, Olive stands alone in a bedroom at her son’s wedding, eavesdropping as she is being talked about by his bride. Her dress is mocked—a dress she loves, printed with giant geraniums—but what stings most is her daughter-in-law’s discussion of how hard Olive was on her son. Olive argues in her head. “…deep down there is a thing inside me, and sometimes it shoots blackness through me. I haven’t wanted to be this way, but so help me, I have loved my son.” But the argument isn’t enough, and Olive is left alone with her hurt and shame and her understanding that love that cannot be expressed warps and injures.

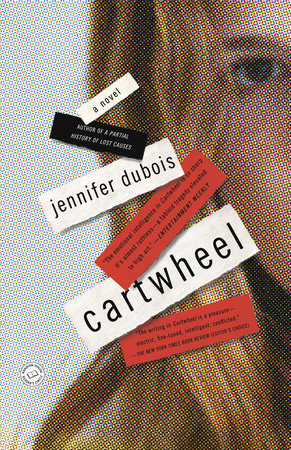

Cartwheel by Jennifer duBois

What do you do when you get a call informing you that your bright, independent daughter, who is spending her junior year abroad, is in jail for murder? Jennifer duBois’s Cartwheel is a compassionate and insightful exploration of a ripped-from-the-headlines nightmare scenario. When the story opens, Andrew Hayes has just landed in Buenos Aires, ready to rescue his daughter and sort out the situation, but already the tabloids and internet sleuths have begun to comb through Lily’s online presence and form their narratives, and he must confront the many versions of his daughter sweeping across the internet. Jennifer duBois’s subject is how we reveal ourselves in the stories we tell, and how in the search for truth, truth can become ever more elusive.

The Green Road by Anne Enright

The premise of this marvelous novel may seem familiar—four adult children return to their childhood home and their ailing mother, possibly for the last time—but Anne Enright’s prose is so precise and gorgeous, her characters so closely observed, that the situation feels completely fresh. The novel centers on Rosaleen, the prickly matriarch who plans to sell the family home, and her relationship to each child. Every chapter is as complete as a short story, and we get to know each family member deeply. In one of my favorite chapters, the eldest daughter (and aptly named) Constance—prosperous, matronly, and beleaguered—takes an epic trip to the grocery store while her siblings converge on the house. With wit, restraint, and unsentimental frankness, Enright captures the bristling rage and tenderness in this family. In my margins I wrote, I wish so much to write something like this!

The post 8 Books about the Power Dynamics Between Parents And Children appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : 8 Books about the Power Dynamics Between Parents And Children