It can be too easy to write villains— people stunted and incapable of love or compassion—when we write about opponents of our politics, especially in short stories, which have so much less space to detail nuance. Sometimes writing about villains and pointing the finger is necessary in a world that turns away from the victim. The raison d’etre in these polemic stories is to reveal the bad guy for his badness. “Cat Person” by Kristin Roupenian is one example. But there are also stories that resist easy answers and reveal the gray area between revenge and justice, kindness and complicity, defensiveness and love’s protectiveness.

The stories in my debut collection, The Rock Eaters, are anything but apolitical. The first story features a school shooting and a neighborhood overseen by angels that sends for an Instagram prayer group to protect them (#ThoughtsandPrayers). Another story considers a group of Latina girls, already world-weary of racism, confronting the whitest girl they’ve ever seen. Latin American superheroes storming the US border headline another. The stories drop weirdness and exaggeration onto stages of political hot topics—race, class, immigration, gun violence, toxic masculinity, and feminism—to disarm the reader from their easy cheat sheets of right and wrong. In most of these stories, the worst harm comes from the best intentions: protect those you love, be fierce in your justice, be gentle in your mercy. I suppose I have a fascination with understanding why we are capable of inflicting such sorrow and hurt in the world alongside having such capacity for love.

Here are seven political stories that resist easy answers:

“The Finkelstein Five” in Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei Brenyah

An act of horrifying violence makes the national news, a white man beheading five black kids with a chain saw in “self-protection,” galvanizing a movement of people standing up to racism. The narrator of this story has every right to be furious and to want justice. But in a world determined to cast him aside, that wants him to keep quiet, that won’t allow true justice, he has to grapple with the meaning and consequences of retributive violence.

“Lulu” in Land of Big Numbers by Te-Ping Chen

In Communist China, a brother and sister take diverging paths: one radicalizing and one becoming complacent. The narrator watches his sister Lulu throw her life into bringing awareness via social media to atrocities committed by the party to dissidents. He begs her to stop, thinking she is throwing her life away; there’s no way that she won’t be caught. And she is caught, again and again. He just wants her to have a normal apolitical life like the one he has, playing competitive video games. How easy and sympathetic it is in this story to want a normal life. When any chance of protest seems hopeless, why not give up? Both of the siblings’ choices are equally heartbreaking.

“Exotics” in Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Moniz

This story details a horrific act by people of privilege in a secret society. This story, however, chooses to focus not on the society-members, who are villainous enough, but the people employed to serve them, the waitresses, cleaners, kitchen staff. Driven by their own needs, by capitalism, by wanting to keep their own families in the green, they are lulled into complicity.

“Skinned” in What it Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah

Ejem is a feminist in a world where upper-class women are granted clothing only by their association with men: fathers before they come of age and husbands when they are married. Well-past the age she should have been married, which is scandalous in itself, Ejem decides to wear clothing granted by no man, a scandalous “self-cloth.” In this story, it’s other women who are the greatest enforcers of the code: “You don’t get to be covered without giving something up; you don’t get to do that,” one of her good friends says. But in the margins of the story are women of the servant class, and the finale of the story is a wonderfully complex moment of intersectionality of class, race, and gender, the privilege of Ejem’s feminism becoming apparent to her.

“Boys Go to Jupiter” in The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans

This story begins with a college girl donning a confederate flag bikini because she looks good in it and escalates when a picture of her in the bikini finds its way to her college campus. Angry, plagued by the death of her mother and her best friend’s brother, she escalates the situation with a giant “eff you” to her college-mates who want to cancel her. The story escalates to a dramatic confrontation between her and the rest of the school, her refusal to take responsibility taking centerstage. The more we learn about her, the more complicated this refusal seems.

“Psychological Operations” in Redeployment by Phil Klay

A veteran of the Iraq war is back in college and asked how he could kill other Muslims by another student on campus. What follows is a rollercoaster of psychology as the vet tells his story, moving through excuse, blame, admission, denial. Their attempt to understand each other ends in a deeply powerful non-answer that leaves the reader as stunned as the narrator.

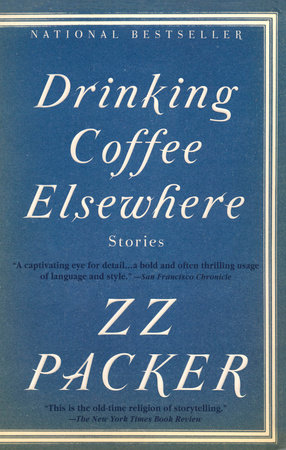

“Brownies” in Drinking Coffee Elsewhere by Z.Z. Packer

In this classic story, a Girl Scout troupe of Black girls from Atlanta goes to summer camp. They think a white girl called them a racial slur, and they plan their revenge. But it turns out the situation is not what it seemed, and the story delivers what could have been a straightforward take on racism, but instead is an incredibly complicated take on cruelty.

The post 7 Short Stories about Political Issues That Resist Easy Answers appeared first on Electric Literature.

Source : 7 Short Stories about Political Issues That Resist Easy Answers