Writing my first poetry book As She Appears was a journey for me as a 41-year old debut poet—I was waiting to find poets like me, who were queer and Asian American. It was a careful writing over a decade, as I considered all of the ways that women—Asian American women, Chinese American women, queer women, and all of their intersections—are distorted and diminished. To come out on the other side, I sought to write about the ongoingness of being a queer women of color and arriving in love exactly as we are.

Today, I am building my own canon of queer women writers of color. The rigorous and inspiring work of these seven poets is a testament to the community of abundance we are living in, in conversation with our elders across the generations. Inventive free verse and hybrid forms, collections that combine layers of research, theory, and diasporic community are only some of the ways in which these poets are imagining into and considering our present, past, and possible futures. Throughout, the work is tender, transformatively joyful, declarative, collective. The work continues, and there is so much to celebrate and honor.

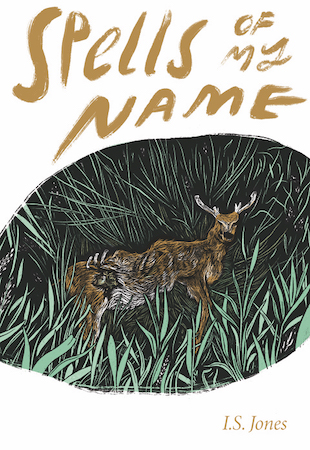

Spells of My Name by I.S. Jones

In this assured debut chapbook, speakers search and don’t settle for easy answers; instead, they take a long look, following the shadows and name what is found there. Jones writes about the complexities and clarities of identity as a Nigerian, an American, and as a queer person, using interview and self-portrait verse forms, reshaping the frame of inquiry. “Violence & hope made me an American” co-exists with erasures in the interview poems. This could be censorship, redaction, erasure, or disclosures that are part of a private knowing. Jones does not let any word pass without imaginative notice—a poem about misremembering esperanza to mean “wild horse woman” turns into “a thousand grandmothers/ galloping in the dark.”

Imagine Us, the Swarm by Muriel Leung

Muriel Leung’s second collection is a seven-sided hybrid swarm, merging theory, cancer biology, history, autobiography, and essay into an expansive lyric of interrogative grief:

“Such myths we prepare for ourselves.

In a singular language—a cleansing.

That absence can feel like relief.”

Silences speak in staggered arrangement, the ellipses following like a trail of bees—perhaps signaling time, breathing, repetition, possibilities, omission. This is the swarm of several lives along with the ghosts. “I set out to write a book about [ ] but it was about [ ] instead.” Absences are presences; footnotes expand deeper into narrative, charting the speaker’s parents diagnoses with cancer and the disease’s cellular progression, while tracking the legacy of anti-Asian hate in America. Parallelisms swarm, the generational labor of living with trauma overwhelms, a migratory suffering. At the same time: the speaker kisses the flood, which kisses back. Vengeance is repair. The possibilities of the swarm: a building that “becomes true in its time.” Leung takes us there with “the clarity of bells.”

The Best Prey by Paige Quiñones

The electric poems of Paige Quiñones’ first book glow with heat, each taut line suspended and sharpened at its edge. Distinctions in desire—lust, aggression, pain, diversion—are less clear and often fleeting to its softer, tender side. Quiñones writes of desire’s contradictions in all of its mess, the speaker boldly declaring in the opening poem: “I am complicit.”

Throughout the collection, the speaker and her lovers shift and transform, animal to animal, between predator and prey. There is a fable-like haunting in these lyric narratives, often with italicized dialogue cutting through as a spectral threat. The intimacies shift as the poems travel from Puerto Rico to Southern California, to the quieter spaces of a hospital and a museum. Quiñones’ restless lyric compels as it unfurls:

“low howl in my belly

at the sight of you between my thighs.

The impossibility of the thing does not stop me demanding it.”

Salt Body Shimmer by Aricka Foreman

Reading Aricka Foreman’s debut is to fall into breath and breathlessness, as the lines flow and turn without stopping. She writes:

“When the station’s stuck between suffer

and c’est la vie, who in a body like this

can afford to believe in reincarnation.”

Emotions are conflicting, simultaneous. Everything permeates—there is no separation or relief. Foreman’s lineation, alignment, and spacing create different music with varying tempos depending on their arrangements, as well as unexpected visual and psychic experiences on the page. These lyric poems accumulate, naming violence and its generational harms, and the daily living with “language in limbo.” The speaker says:

“I try

to wrangle these roots respectable but

this morning keeps getting in my way.”

Desire, too, is a journey, and the slow burn of Foreman’s verse is a spellbinding intimacy of precision:

“when we say we want tenderness we mean

we haven’t found a punishment we can live with.”

Descent by Lauren Russell

In this book-length work, Lauren Russell writes into the archive of family and history—what we cannot know, and what and who has been denied preservation: “Because history is neither the truth as it happened nor necessarily the truth we most want to believe.”

This complex, layered book came out of years of research. In 2013, Russell acquired the diary of her great-great-grandfather, Robert Wallace Hubert, a Confederate Army captain who fathered twenty children by three of his former slaves—one of which was Peggy Hubert, Russell’s great-great-grandmother. The result is a hybrid collection of voices, similar to a theater piece, intertwining poetry, prose, images, handwritten and typed documents, records, and fragments, overlaying past and present.

Russell’s contemplations are generative, expansive, letting the silences speak, imagining into the gaps, invoking Audre Lorde’s term “biomythography” to give Peggy a voice and a life on the page. Her excavation of her familial past is rigorous and skeptical:

“She has swallowed her voice like a seed. We want to believe that she is a heroine here, that she has some agency, that for once in her life she was given a choice.”

Russell’s sensory poetic precision and exhilarating intellectual curiosity invite a careful read as she dwells in the archive’s indeterminacy.

Unearth [the Flowers] by Thea Matthews

Through this debut collection, Thea Matthews enacts a vital resurrection, each poem a flower and a declaration on a journey of transformative healing. Matthews, a queer Black Indigenous Mexican poet, writes: “I am Evening Primrose/ I take responsibility for all that is mine,” a floral symbol of eternal love and beauty. Here, beauty coexists with surviving violence and both are brought out into the light, in anger and self-liberation:

“Protea remains

unfolds

dances with the flames chanting

Black and breathing

Black and breathing

Black and breathing.”

These poems bloom in their emotional depths and clarity, gathering in power and connectedness. The speaker’s body is rooted in the land, in community:

“I awake with sun

I renew my vow to life.”

Our Andromeda by Brenda Shaughnessy

The intergalactic expanse of this collection is a marvel. Brenda Shaughnessy’s echoing (and orbiting) music and use of repetition amplify her enchanting narratives, which are made more disarming by their wit and play. Shaughnessy’s speaker invites the reader into their world as a chosen one:

“Did you receive my invitation?

It is not

for everyone.”

And the poems are tender, too, addressing the speaker’s longing for more sisters, her misguided love for a woman at age 23, and most powerfully, the vision of Andromeda, an alternate world of ease for her young son in the book’s final long poem. In this poem that speaks to the enduring, transformative power of family love and a child’s (and a mother’s) imagination to bring us closer to being and knowing, she writes:

“Our Andromeda, that dream,

I can feel it living in us like we

are its home. Like it remembers us

from its own childhood”

The post 7 Poetry Collections by Queer Women of Color appeared first on Electric Literature.