Andrew Ridker, author of “The Altruists,” recommends fiction on how debt ruins lives

When I was young I used to play the Bank Game. I don’t remember the rules, only that whenever my parents took my sister and me to the house of certain family friends for dinner, us kids would run upstairs and form two competing banks. At some point during the game, the boys’ bank would become indebted to the girls’ bank, or vice versa, and a winner was declared.

In retrospect, the notion of four suburban Jewish kids play-acting as bankers while their parents eat dessert downstairs strikes me as a little on the nose. Nonetheless, I’ve always been fascinated with money — who has it, who doesn’t, and what people do when they get it. It’s a fascination that animates my novel, The Altruists, in which a father invites his estranged children home in an effort to recapture the inheritance left them by their late mother.

The Altruists belongs to a tradition of novels in which money, or its absence, is not only a plot point but a central theme. In Little Dorrit, Charles Dickens took readers inside Marshalsea, the London debtors’ prison where his own father had done time. Fred Vincy’s debt in Middlemarch threatens his relationship with Mary Garth, while Rosamond Vincy’s spending forces her husband, Dr. Lydgate, to take on debt of his own. But the Victorians don’t have a monopoly on debt. Here, right on time for tax season, are seven works of fiction that all explore what happens when the bill comes due.

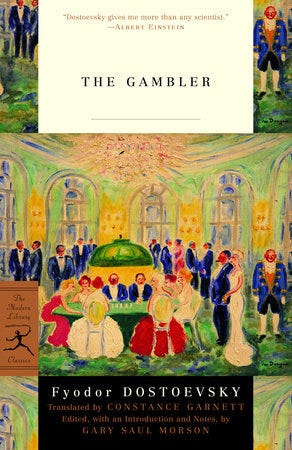

The Gambler by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Gambling debts lie at the center of this slapdash work by the Russian master. But Dostoevsky’s novella is not just about debt; it was written in order to pay one off. In 1865, pursued by creditors, Dostoevsky sold the rights to his collected works to an editor. The contract stipulated that he would produce a new novel for the editor by November 1, 1866, or else the editor would acquire, for nothing, exclusive rights on all future work for the next nine years. Dostoevsky hired a twenty-year-old stenographer, Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina, and dictated The Gambler to her over the course of twenty-six days. (The two were later married.) The resulting work, which engages a subject with which the author was intimately familiar — roulette addiction — is messy, but remains memorable for its depiction of the gambler’s psychology. “At that point I should have walked away,” our narrator explains, “but within me was born a strange sort of sensation, a sort of challenge to fate, a sort of desire to give it a flick, to poke my tongue out at it. I bet the highest stake permitted, four thousand guilders, and lost.”

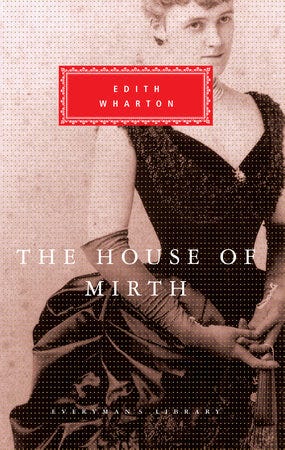

The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

Lily Bart also has gambling debts — and that’s not counting the money she owes Gus Trenor, the “red and massive” husband of her best friend Judy. For Lily, playing bridge “was one of the taxes she had to pay for [her hostesses’] prolonged hospitality.” She soon finds herself in the unusual position of being a broke socialite, desperate to maintain her lifestyle by marrying rich. Her friend and potential suitor Lawrence Selden sums up the situation: Lily is “so evidently the victim of the civilization which had produced her, that the links of her bracelet seemed like manacles chaining her to her fate.” Wharton’s breakout novel brilliantly, ruthlessly depicts Lily’s attempts not to succumb to that most unspeakably humiliating fate: downward mobility.

Hunger by Knut Hamsun

After being turned down for a number of jobs, including debt collector, the nameless protagonist of Hunger sets out wandering the streets. His clothes are shabby, he’s pawned his possessions, and he owes the landlady rent. He longs to write an article “about the crimes of the future or the freedom of the will, anything whatever, something worth reading, something I would get at least ten kroner for.” Eventually he sells an article, but the money spends fast, and soon he’s hungry again. Notable for its psychological acuity and its break with social-realist tradition, Hunger remains a compulsively readable novel, by turns humorous and harrowing, about the trials of a starving artist.

Seize the Day by Saul Bellow

Tommy Wilhelm is a failed actor, a failed salesman, a college dropout, and has recently separated from his wife, to whom he owes child support. “In the old days,” Wilhelm thinks, “a man was put in prison for debt, but there were subtler things now. They made it a shame not to have money and set everybody to work.” Wilhelm’s father refuses to support his son financially — “Why didn’t he? What a selfish old man he was! He saw his son’s hardships; he could so easily help him. How little it would mean to him, and how much to Wilhelm! Where was the old man’s heart?” — leading Wilhelm to hand over the last of his savings to Dr. Tamkin, a psychologist who plays the commodities market. But when Wilhelm takes a loss, Tamkin disappears, and Wilhelm finds himself in the midst of a great crowd on Broadway, seeing “in every face the refinement of one particular motive or essence — I labor, I spend, I strive, I design, I love, I cling, I uphold, I give way, I envy, I long, I scorn, I die, I hide, I want.”

Twenty Grand by Rebecca Curtis

In a time of runaway inequality, subprime mortgages, and student loan debts so massive they can only be thought of as fictitious, it’s a wonder more contemporary American literature doesn’t engage directly with the question of money. One writer working to correct this oversight is Rebecca Curtis, whose excellent collection Twenty Grand (subtitled And Other Tales of Love and Money) is full of clear-eyed, unsentimental stories of bankrupt theme parks and bad waitressing gigs, told with biting humor and occasional forays into the fantastical. In the title story, the narrator’s mother spends an old Armenian coin, a family heirloom, when she can’t find any other change with which to clear a tollbooth. The coin, it turns out, is worth $20,000. The story’s brilliance lies in its fusion of a 19th century plot — the twist is like something out of Guy de Maupassant — with closely-observed depictions of contemporary middle-class life.

The Turner House by Angela Flournoy

In 2008, as the country undergoes a financial meltdown, Lelah Turner finds herself evicted. Stuffing underwear into trash bags, she takes a quick inventory of her life. “Furniture was too bulky, food from the fridge would expire in her car, and the smaller things — a blender, boxes full of costume jewelry, a toaster — felt ridiculous to take along. . . . Where do the homeless make toast?” She moves into her mother’s empty house, which is worth one tenth of the $40,000 her family owes on the mortgage. Her siblings are torn on what to do with it: hold onto the property in case the market rebounds? Stop making payments and walk away? Flournoy’s National Book Award-nominated novel follows the Turners as they navigate a city in decline, from their house on Yarrow Street to the unemployment department’s “Problem Resolution Office” to a pawn shop called CHAINS-R-US where Lelah sells her childhood flute. The house itself functions as setting, character, and metaphor — for the Turners, Detroit, and the haunted American Dream.

Refund by Karen E. Bender

Bender’s collection, a National Book Awards nominee, tackles financial precarity in all its forms, but debt takes center stage in the standout title story, in which a couple sublets their subsidized Tribeca apartment for far more than it costs them to live there. When the Twin Towers fall, the couple’s traumatized tenant demands a refund. The negotiations soon get out of hand. “I am requesting $3,000 plus $1,000 for every nightmare I have had since the attack,” she writes. “You owe me U.S. $27,000, payable now.” The story’s startling climax ponders the debt of survival. “What did one owe for being alive?”

Anything for Money

About the Author

Andrew Ridker is the author of The Altruists. It will be published in seventeen other countries. He is the editor of Privacy Policy: The Anthology of Surveillance Poetics and his writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Paris Review, Guernica, Boston Review, The Believer, St. Louis Magazine, and elsewhere. He is currently an Iowa Arts Fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

7 Novels About Being Broke was originally published in Electric Literature on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Source : 7 Novels About Being Broke