I don’t want to read about mangoes. Their freshness, their sweetness, their broadleaf trees with laden boughs. I don’t want to read about their pickled tartness, or how their ripening smell signals approaching summertime. In fact, I don’t want to read about the Indian summer either, unless what I’m reading conveys how truly crushing its heat is. In essence, I don’t want to read India as written for its diaspora—the longing for an imagined homeland—or India written for a colonial imaginary, which, in my experience, often shows up on the page as the same kind of longing.

There was a time, though, when I lived for this stuff—and that’s also when I lived in the UK. Back then, I wanted to gorge on literary mangoes, on loss, on a simmering outrage at appropriation that was so perfectly caste-blind that it always already exonerated me. This was also, unsurprisingly, the sort of writing that was easier to find, the kind that made—and still makes—a variety of international bestseller lists.

But then, I moved to India; I lived, worked, dated, dreamed, sweated in India. And I knew I needed something else. I needed books that were sharp and true and felt, but most of all, that were less interested in the subaltern speaking back to empire than they were in writing without reference and deference to empire at all.

Here are seven women authors whose work is not nearly as widely read as it should be, but who write India as it feels: shorn of nostalgia, mythologized pasts, poverty porn, and for the most part, mangoes.

Shama Futehally

My mum lent me her copy of Tara Lane when I was at the peak of my frustration with South Asian fiction, and it was exactly what I needed. Shama Futehally’s debut novel—but by no means her first significant literary work—is a true treasure; a coming of age story set within an old affluent Muslim family whose world is beginning to fracture. As the narrator Tahera—or Tara (who shares a name with the small Bombay lane where their family home sits)—reflects: “When our house of cards collapsed, it would fall on all sides, in a single totter.”

Futehally’s graceful, precise prose navigates family dynamics, labor strikes, and Tara’s interior world with equally deft poise. In a long tradition of literature that elevates the ordinary to the extraordinary—Carol Shields, Anne Tyler, Rachel Cusk—Shama Futehally and Tara Lane deserve lasting pride of place.

Meena Kandasamy

I’m definitely trolling myself by including Women’s Prize-shortlisted poet, author and translator Meena Kandasamy on this list, but I came to her work so late that I want to rectify a similar potential loss on everyone’s bookshelves. Her 2017 novel When I Hit You; Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife is a gripping story of a young woman living with her abusive Marxist husband.

As someone who has wasted too much time in thrall to socialist men, I loved this exploration of gender, idealism, and the seductive draw of politically engaged men. For example: “To fight the evils of capitalism, we required the staunchest warriors. He was one, and he could make one out of me.” Hard relate. Above all, though, Kandasamy’s novel is a story of one writer’s struggle to create work within and against incredibly oppressive odds. As her narrator says, “The number one lesson I have learned as a writer: Don’t let people remove you from your own story.” Kandsamy—in her poems, books, and even her tweets—never does.

Aditi Patil

My friend who loaned me her copy of Patriarchy and the Pangolin: A Field Guide to Indian Men and Other Species described it as “perfectly capturing millennial Indian women’s climate angst”—something we both share, but rarely see so well represented. Conservationist Aditi Patil’s debut 2020 book is part-memoir, part-field research; the story of two women making their way through Gujarat’s farms, fields, forests, and bureaucracy. Here they’re faced with every species of intractable Indian man as they seek to uncover stones usually left behind by data: women farmers, nonhuman life, indigenous peoples.

Describing herself as “the poor woman’s David Attenborough,” Patil’s book sparkles with a delightfully Indian humor. Roadside cows ‘”wonder… what failed questionnaire sheets taste like” and more than one potential conflict is diffused because “The moment passed, like all the millions of moments that have historically passed when men haven’t noticed what women said.” In Patil’s own words, Patriarchy and the Pangolin is a book “about what it means to be alive in India. And to be alive to India.” And it is just that.

Sharanya Manivannan

“Some days you sparkle like a teenage vampire. Some days you feel as though you’ve walked through the remains of an exploded dhrishti pusanika, which is to say, fucked.”

Unlike the other writers on this list, poet and author Sharanya Manivannan—who grew up between Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and South India—leans deeply into cultural and spiritual specificity, and invites her readers to follow. She’s the author of two poetry books, a collection of short stories, a novel, and most recently, a graphic novel about mermaids that she illustrated herself(!). Across genre, all of Manivannan’s work glows with a luminous depth and a thorough relishing of language at every turn. This includes my favorite, The High Priestess Never Marries, a collection of short stories about women living on their own terms that shines long after the last page.

Manjima Bhattacharjya

Can feminism and fashion be allies? This is one of the many questions Manjima Bhattacharjya (one of the best feminists I know) explores in her intrepidly reported book Mannequin: Working Women in India’s Glamour Industry. From going backstage at India’s most prestigious fashion event (thanks to meeting two models outside the hotel toilets—what Bhattacharjya describes as “the most significant day in my Ph.D. life”) to interviewing countless working women from a wide variety of backgrounds, this debut book uncovers the lives of women in fashion as existing, consistently, “between spectacle and surveillance.”

Spanning body politics, labor protests and feminist ideas of “objectification,” Mannequin leads us through an unflinching analysis of how neoliberalism has deeply shaped India; an economic system in which models serve as the very embodiment of globalization. Except the thing about globalization is that not everyone can participate in it —including, often, the women themselves.

Nisha Susan

Co-founder of the award-winning feminist website The Ladies Finger, Nisha Susan is a writer who I first encountered as an editor. She was the first person who showed me how to make writing that endures, and most importantly, what an editor can do for a writer. When I went on to become an editor myself, it was her smart, guiding hand I tried to channel. All this to say that I was entirely primed to love her debut short story collection The Women Who Forgot To Invent Facebook and Other Stories—and it did not disappoint.

Susan writes millennial India the way it feels for many of us: funny, painful, violent, absurd, and in turns bound together and fractured by digital technology. This sharp, witty collection also manages to feature pretty much every variety of Indian fuckboy I’ve ever encountered, which, given their expansive range, is no small feat.

Priya-Alika Elias

Speaking of desi fuckboys, my favorite chronicler of their insufferable ways is Priya-Alika Elias (see: “DJs are the root canals of people”), the author of Besharam: Of Love and Other Bad Behaviors. A collection of funny, fierce, heartbreaking essays, Besharam (the Hindi word for “shameless”) ranges in topic from internet culture to “aunties” to the problem with telling your friends to just “dump him.” In it, Elias writes:

“How can I describe the specific wound left on online dating sites by white women who say ‘only white men’ or that left by white men who say ‘you’re attractive for a (X ethnicity)?… We know what happens to a wound when it festers.”

Spanning the author’s life in the U.S. and India, Besharam is a memoir that’s really a survival guide for South Asian women the world over. As an essay titled “Body” reads:

“I was a brown girl in a wasteland of blinding whiteness and it never occurred to me that I was worthy of being cherished and loved.”

At every turn in her debut book, Elias takes our faces between her hands and tells us we are worthy, worthy, worthy.

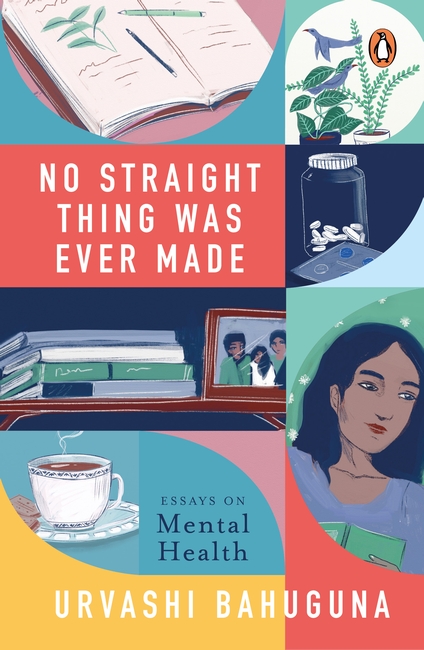

Urvashi Bahuguna

Poet and essayist Urvashi Bahuguna is the voice in Indian writing I feel I’ve always been looking for: graceful, sharp, and most importantly, rooted in India without insisting on cultural identity at every turn. The young author of an exquisite debut poetry collection Terrarium (whose launch I attended at an indie bookstore in Goa, the Indian state where I live and where Bahuguna is originally from), it’s her 2021 book No Straight Thing Was Ever Made: Essays on Mental Health that announces Bahuguna as a literary force to be reckoned with. In it, she writes:

“We knew respectability was no antiquated need for most people around us, and that stigma and judgment were a stone’s throw from where any of us stood.”

Simultaneously soft and crystalline sharp, Bahuguna’s essays range in scope from family to fear to writing to birds— the attempts of a young woman to trace the patterns of her mind and her life, all the while remaining firmly rooted where she stands.

The post 7 Indian Women Writers You Should Be Reading appeared first on Electric Literature.